Despite covering a relatively small area, the Old City of Jerusalem abounds with important sites and a history of religious, cultural, and architectural dimensions related to the heritage of the three monotheistic religions. Islam and Arab civilization dominated throughout the past 14 centuries, during which time the Holy City enjoyed tranquility and peace that preserved it from the destruction of previous eras. The features of this cultural heritage remain visible in many corners of the Old City and are testimony to a unique diversity and originality rarely seen in other cities.

Yet this rich architectural heritage is often ignored due to the common, though misleading, belief by visitors, and even tour guides, that the only sites worthy of visit are Al-Aqsa Mosque, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Western Wall, and perhaps the walls of the Old City itself. Most existing tours focus on these sites, mainly due to a lack of awareness about other locations and the absence of resources to bring these sites to the attention of travel agents and specialized tour guides and perhaps to the individual independent traveler. The maze of narrow streets in this jewel of a city can be daunting, and the façades of buildings give little away about their history or occupants.

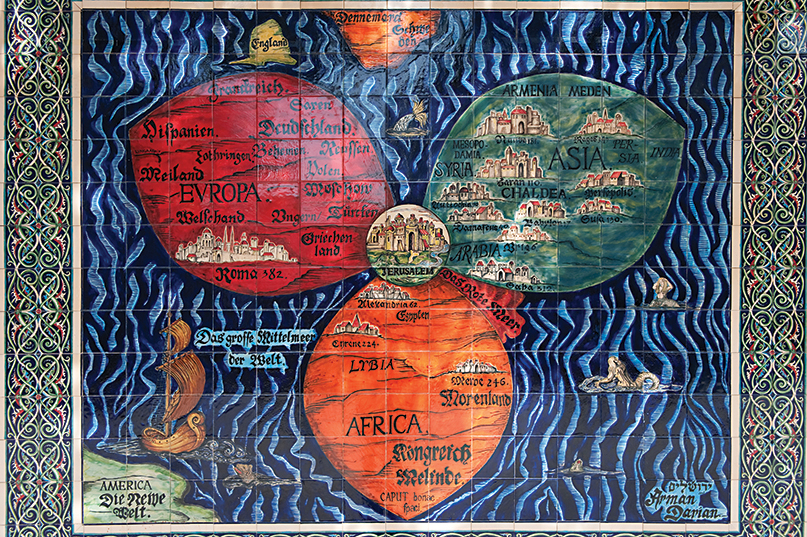

The Old City of Jerusalem remains one of the most preserved and inhabited ancient cities of the world. Throughout the years, the city has attracted and drawn many people from all over the world, with each leaving a trace on the overall cultural heritage and demographic diversity that actually exist in it. This cultural diversity is still present in the city in various forms, often completely assimilated and part of the Palestinian fabric, whereas in certain other cases it exists in a certain balanced equilibrium that reflects the ongoing perpetual respect for the diversity that for many centuries commanded the soul of city. Diversity in Jerusalem is a competency. It is an essence of its attractiveness and a true reflection of the natural progression of its complex history. Inherent within these words is the philosophical question: How is Jerusalem’s diversity protected, particularly since half the world claims a part of the city for itself? Indeed many children of the world sing for Jerusalem as they grow up, before even having the chance to visit the city. It is in their veins, whether they are Christian, Muslim, or Jewish. It is culturally engrained in their cognizance even if they are not religious. This link to the city instigates an embedded need to protect, preserve, and promote the diversity that lies within its labyrinth of streets, alleys, courtyards, spaces, and attics.

There is no doubt that the existing Palestinian diversity that came about as a result of an exhaustive history of pilgrimage, religion, and even wars is not well understood, and the Western media and perceptions of the city divide it into four quarters, a division that hardly reflects the original Roman construction and design of the city on one hand and its Islamic functionality, market distribution, and ethnic diversity on the other. The city has provided its residents and visitors with a number of specialized streets, most of whose names reflect their role and function. Hence, Al-Attarin is the spice street, and Al-Lahhamin is the butchers’ market, and Khan ez-Zeit is the oil market. The Via Dolorosa hosts many of the Old City’s churches, most of which are in what is known as the Muslim Quarter. The influence of Al-Aqsa Sanctuary, the Holy Sepulcher, and the Western Wall is evident upon the religion of the people who live within and around these neighborhoods. But also, this spread of the various sites and communities in the Old City calls for a different understanding of its demographic and cultural depth and diversity, an element that is often misunderstood, marginalized, and bypassed in most tour programs and itineraries.

Background to the Old City of Jerusalem

Jerusalem, the capital city of Palestine, sits at around 750 meters above sea level, although some of its surrounding mountains exceed that height by 100 meters or more. Jerusalem sits on top of the mountain range that acts as a dividing line between the Jordan Valley and the desert to the east and the Mediterranean Sea to the west.

Situated in the Mediterranean climatic zone, Jerusalem’s climate is influenced by its topography and proximity to the sea. Average temperatures vary from 8 degrees Celsius in January to a record high in June of 44 degrees Celsius. Snowfalls may occur in the city and its higher elevations during the winter. The average annual rainfall totals 550 millimeters, mostly occurring in January and February, a figure that is close to the average annual rainfall in London.

Jerusalem: City of Monotheism

Jerusalem’s uniqueness lies in the fact that the followers of the three monotheistic religions – Islam, Christianity and Judaism – consider the city to be holy. While its holy status has brought the city renown and prosperity over the years, this has been at the price of suffering and discord for its inhabitants.

The history of the city is woven from beliefs about religious events, often entangled with folklore to create a mix of reality and fiction, of facts and imagined history. This complex background is reflected in those who revere the city.

For Jews, Jerusalem represents the city of King David and his son Solomon, the city to which the Ark of the Covenant was transported, and where Solomon built the Temple. It is a city of longing, passion, and nostalgia for prophets, the exiled, and those deprived of residence in it. Jerusalem is referred to hundreds of times in the Old Testament.

For Christians, Jerusalem is the city visited by Jesus Christ as a child and also as an adult; it was in these neighborhoods that he preached his message of love, peace, and salvation, and performed miracles. According to the Christian faith, Jesus was imprisoned, crucified, killed, and buried in Jerusalem. The city holds the route of his suffering and the place from which he rose and ascended to heaven. Jerusalem is the birthplace of the early churches, the destination of pilgrims and visitors, and the place where monks, nuns, and clergy of all sects and beliefs gather.

For Muslims, Jerusalem is not only connected to God’s prophets, such as David, Solomon, Jesus, and the others mentioned in the Qur’an, but it is also a Holy Land blessed by God. It is the site of the Isra and Miraj (the night-journey miracle), the first qibla (direction for Muslim prayer), and a destination for believers to visit alongside Mecca and Medina. In Muslim literature, it is the place of the coming Day of Judgment and the site where some of the companions of the Prophet and other holy men have been laid to rest. The city holds the famous Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, the third holiest site in Islam.

The Wall and Gates of Jerusalem

The wall of the Old City of Jerusalem is an impressive feature and remarkable for the fact that it is complete. The visible parts of the wall were built during a single architectural era and include geometric decorations, motifs, and writings representative of the architectural schools of the Mamluk and Ottoman periods. Beyond its historical value and significance, the wall is essentially an embracing protector of the Holy City and its heritage.

The current wall of Jerusalem was built at the beginning of the Ottoman era upon the orders of Sultan Suleiman I (Suleiman al-Qanuni or Suleiman the Magnificent, 1520–1566 AD). The actual construction of the wall took place during the period 1537–1541 AD and took almost five years. Its height ranges between 5 and 15 meters, depending on the location, and it is around 1.5 meters in width in some places, although it is 3 meters in width in other locations, particularly at its base.

The wall has 34 watchtowers, the most well-known being Stork Tower (1538–1539 AD) and Sulfur Tower (Burj al-Kibrit, 1540–1541 AD). It also features some 379 arrow slits, 17 machicolations, and many other military defense features such as towers, turrets, observation terraces, low entrances, and moats around some sections. The wall acts as a canvas for elaborate decorations: layers of embossed floral motifs that depict small flowers, fruits, leaves, tree branches, and stars of various styles.

The current Jerusalem wall has seven open gates: five ancient and original ones, and two that were added later. The five original gates are Damascus Gate (1537–1538 AD); Herod’s Gate (1537–1538 AD); Lions’ Gate (1538–1539 AD); Zion Gate (1540 AD); and Jaffa Gate (1538–1539 AD).

Damascus Gate, which is probably the most impressive gate, is a prime example of sixteenth-century architecture in Jerusalem and the most opulent in both size and in architectural and decorative design. Although known by many names throughout history, the name Damascus Gate is the one most commonly used. Its Arabic name, Bab al-Amud, refers to the column (amud) that formerly stood in the inner courtyard of the gate and featured a statue of Emperor Hadrian. This was in keeping with the common practice of decorating Greek and Roman cities with statues of rulers and pagan gods.

Suqs and Bazaars

Traditional and contemporary commercial life within the Old City of Jerusalem comes alive in this fascinating trail. Introducing the architectural facets of the khans and the bazaars, the historical centers of commercial activity, this trail guides the visitor through the narrow thoroughfares crowded with peddlers selling their wares and bustling with shoppers and small carts transporting goods. The suqs are a unique mélange of daily social interactions, traditions, pungent scents, and the variety of the Orient. Here you can find Jerusalem’s famous sesame bread (ka’ak b-sumsum); Zalatimo’s sweet pastry (mutabbaq); Jafar’s sweet-cheese dessert (kanafeh); and Al-Amad’s dense sweet tahini confection (halaweh) in a variety of flavors. Stop for a bowl of Abu Shukri’s famous hummus; drink coffee and tea in Suq al-Qattanin; relax in the sunshine in Suq Aftimos and al-Dabbagha; or stock up on spices in Suq al-Attarin. Stations along this trail include Suq Khan al-Zeit, Suq Aftimos and Al-Dabbagha, the Bazaar and Suwaikat al-Husur (straw mats), the Roofs of the Three Suqs, Suq al-Lahhamin (butchers), Suq al-Attarin (spice traders), Suq al-Khawajat (well-off people and foreigners), Khan al-Sultan, and Suq al-Qattanin (cotton traders).

Women in Architecture

Jerusalem’s significance in Arab history, and particularly in Islam, attracted several wealthy women to the city. Although Arab Islamic society was primarily patriarchal, women from ruling or wealthy families were able to use their position in society to undertake acts of welfare and charity.

A review of architectural and social activities in Jerusalem during the Islamic eras makes it apparent that a female legacy was introduced into the city at an early stage. The contribution of women in Jerusalem was diverse in scope and included acts of compassion towards Sufis and the poor, providing copies of the Holy Qur’an to the faithful, and constructing buildings for charitable purposes. The architectural heritage of women started early in Jerusalem and dates to the Abbasid era, when the mother of Al-Muqtadir Billah renovated the doors of the Dome of the Rock. There was considerable activity by women during the Mamluk period, represented in the establishment of public and private buildings and structures. The largest house or palace representing civil architecture in Jerusalem is attributed to a woman: Sitt (meaning “madam”) Tunshuq Al-Muzaffariyya. In addition, the largest and greatest social charity organization of the Ottoman era, known as Imara al-Amira, is attributed to the wife of Suleiman I (Suleiman the Magnificent). She was famously known as Khassaki Sultan, and the building she constructed is considered one of the most significant, not only in Jerusalem, but in Palestine and the Levant as well.

♦ Palestinian Dishes

› Maqluba

Maqluba or makloubeh (مقلوبة) is a traditional Arabic dish that is popular in Palestine. It includes lamb or chicken, rice, and variety of fried vegetables, such as tomatoes, potatoes, cauliflower, eggplant, and carrots. Maqluba is served by flipping the pot of cooked ingredients upside down onto a tray, hence the name maqluba or “upside down.”

Maqluba is usually served with either plain yogurt or a simple Arabic salad (salata falahi). It was also known as “the eggplant” because the main ingredient is often eggplant.

Maqluba was served to the leader Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi on the day of the conquest of the holy city of Jerusalem in 1187.

Sufi Institutions and Religious Schools

Although Sufism has largely disappeared in the city, its institutions remain a testament to the role that Sufism played in Jerusalem’s society. Sufism indicates dedication to worshipping Allah (God) the Almighty and shunning the material aspects of life. In this respect, Sufism started with the early stages of Islam and the manner in which Prophet Muhammad and his followers conducted their lives. The religious symbolism of Jerusalem in Islam prompted large groups of worshippers and dedicated Muslims to make it their destination.

Sufism in Islam passed through a number of stages. At the beginning, mosques and private homes were centers for Sufism and its patrons. Later, a common Sufism developed that required a central institution with specific regulations. Sufism followed numerous traditions and rituals that influenced the daily lives and activities of Sufis in Jerusalem, and it flourished during the Mamluk and Ottoman eras.

There were three types of Sufi institution. Linguistically, a zawiya is a corner. In practice, it is a location in which people are brought together, and the term was used to indicate places where Sufis congregated or found shelter.

Khanqa is a Persian word that means home and was used to indicate places where Sufis sought seclusion to worship and recite the Qur’an. In Mamluk literature, khanqa described a mosque and a Sufi home, possibly with a school or dormitory attached to it.

Some Sufi buildings were known as ribat, an Arabic word that indicates steadfastness along borders and strongholds. If the ribat was inside a city and not on a border stronghold, then it referred to a building allocated for the poor, sometimes for widows or divorced women. Over time, these three Sufi types of home came to serve more or less the same categories of people. Regardless of the names given to Sufi buildings, there were no significant differences architecturally or in the administrative and financial operations of these buildings. However, the ribat is distinguishable in that it was a shelter for the poor, referred to as mujawirin (neighbors).

The stations of this trail include Zawiya al-Adhamiyya, Khanqa al-Dawadariyya, Zawiya al-Qadiriyya, Ribat al-Mansuri, Zawiya al-Qirarmiyya, Khanqa al-Salahiyya.

♦ Palestinian Dresses

› Dresses of the Jerusalem Region

› The Ghabani style is noted for its use of Syrian silk embroidered with beautiful motifs in yellow silk thread.

› The Abu Kutbeh style is distinguished by its green and red silk fabric, representing paradise and fire.

› The Al-Asawri style is known for its black-and-red-striped or black-and-yellow-striped silk.

The Demographic Mosaic

Throughout Jerusalem’s history, pilgrims and travelers as well as remnants of dynasties and rulers added to the local mix of people, often maintaining and preserving the city’s rich and diverse cultural heritage identity. Every corner has a story to tell and a secret to discover and explore. The people who live in these various corners are welcoming, although visitors must exercise courtesy and respect as they ask permission to enter.

Stations on this trail include the Indian Corner, the Afghani Corner, the African Community Center, the Assyrian Community, the Armenian Quarter, the Coptic Patriarchate, and the Ethiopian Church.

All are welcome and encouraged to visit the Old City and its surroundings to discover its secrets, to delve into its various historical and cultural fragrances, and to engage and interact with its indigenous community and the pluralism it offers.

» Jerusalem Tourism Cluster is a member of ATHC (Al-Quds Tourism and Heritage Committee), which is the umbrella body that encompasses all the tourism-related organizations that work from Jerusalem (namely, Jerusalem Tourism Cluster – JTC, Tourism and Arts Jerusalem Cluster – TAJ, The Arab Hotel Association – AHA, The Holy land Incoming Tour Operator Association – HLITOA, The Arab Guides Union – ATGU, and the Jerusalem Chamber of Commerce), in addition to delegates from the cultural, educational, and community-based-organization sectors.