In the dusty hilly terrain to the south of Hebron, on dry bedrock ground where shrubs can barely find a way to grow, stands a small house built from concrete blocks. The concrete is surrounded by a metal structure that supports a suspended layer of fabric. It is hard to call it a concrete house, yet it is not a tent. It is something in-between: a draped house that I will call the “Concrete Tent”. The fabric covers the concrete from all sides but reveals it at the front. Obviously, at the moment the photograph was taken, the house was partially undraped and the blue painted door left slightly open. Perhaps someone has just entered inside or left. Their recent presence in the scene is a reminder of an on-going daily life. In front of the house, there are pieces of rock, a pile of concrete blocks, and sparse patches of dry green growth. To the right, a child’s slide is angled, its end directed towards the hard bedrock. Behind the Concrete Tent there is a swing, and further to the back, in the near horizon, there is an Israeli patrol on the watch.

♦ In 1997, Israel declared the status of unregistered lands as state lands on the basis of a distorted interpretation of the Ottoman Agrarian Law. In Area C, around 34% of the lands gained that declaration, 30% were declared as “military firing zones”, 20% classified as “survey fields”, and others designated as “nature reserves” and “national parks,” which left Palestinians with less than 1% for construction – with most of it already built up. Construction in the remaining part is only possible with a permit and within the borders of an approved master plan. However, the Civil Administration has rejected most master plan proposals and declined almost all building permits, leaving 340 peasants and goat-herders in Susiya on the brink of eviction today.

On 4 May 2015, High Court Judge Noam Solberg rejected a petition for an interim order that would freeze the implementation of demolition orders issued against homes in the village of Khirbet Susiya, a tiny encampment of tents and shacks. Here, a few hundred people are still hanging on to what is left of their ancestral lands; in face of the Israeli Civil Administration which could uproot the entire village of eighty structures at any moment. However, after negotiations with the representatives of the village, the final hearing at the Supreme Court as to whether the Israeli Defence Forces could carry out the deed – initially scheduled for August 3 – was postponed given the outrage and escalating tension that followed the burning of an eighteen-month-old boy in Duma, near Nablus in the West Bank. This continued deferral of a decision preserves the ambiguous legal context that has allowed the continuation of a trend which caused the inhabitants of this village to be evicted three times in as many decades. The enforced uncertainty brought about by this situation threatens to push Susiya’s case into an open conflict. Today, the whole village lives on the brink of eviction, awaiting a fateful decision from the pending court hearing.

The Israeli-Palestinian story of build-and-destroy is not new to the conflict. In Susiya, as is the case in other villages within Area C, this story has been well rehearsed on the claim that Palestinian structures have been built without permits and are thus rendered illegal. In fact, Palestinians living in the area do apply for permits, but almost none are ever issued. Thus, the urban informality and illegality of structures is the consequence of a condition brought about by Israel’s discriminatory policies that leave Palestinians who need shelter with no other alternative but to build without permits.

The political geography of urban informality has been conceptualised by Israeli theorist Orel Yiftachel as gray spaces positioned between the “lightness” of legality, safety, and full membership (white spaces), and the “darkness” of eviction, destruction, and death (black spaces). In the Palestinian-Israeli context, Yiftachel associates “Gray Spacing” with the ethnocratic practices of Israel against the indigenous Palestinian Bedouins in the Negev desert. However, an application of the concept inside the Green Line, as I suggest, can also illuminate the urban colonial practices of Israel against the Palestinian peasants, fallahin, in Area C. In this article, I extend my analysis over a spectrum of scales across which the conflict of Susiya unfolds in an attempt to reveal what delineates the borders of the entire village as a “gray space:” how are these borders maintained, and what whitening and blackening practices shift them? Moreover, what is the role of fallahin as both the planners and architects of the village within these processes?

To answer these questions, I base my research on the image of the Concrete Tent that begins this article. At first glance, the most striking element in the Concrete Tent is the tension between the fabric and the concrete that together form its envelope, one of the most primitive elements in architecture. The envelope separates the inside from the outside. Thinking of it as the border, the frontier, the edge, and the liminal brings about the shift that contemporary studies have made in understanding these synonym concepts as complicated, contested territories rather than mere lines. The envelope, as I argue, is no longer a surface but rather a device fully loaded with political content. The hardness of the concrete and softness of the fabric reveal their expressions and political agency. While concrete expresses permanence, formality, and illegality; fabric expresses temporality, informality, and ‘imagined’ legality. Although building without permits in Area C is prohibited regardless of the construction materials, fabric tends to be more tolerated by the Israeli authorities. Thus, the logic behind veiling the concrete with fabric suggests that it is used to exit a regime of visibility. It positions fallahin outside the gaze of the state authorities by blurring the figure of a concrete house as a demolition target against the background of the village in conflict.

The interesting constellation shown in the photograph of the Concrete Tent, where the concrete reveals itself from underneath the fabric while an Israeli patrol is standing in the horizon and watching, also suggests that this practice of the fallahin is not completely secretive. It is rather a tactic that allows Israel to mobilise tolerance – understood here as a mode of incorporating the village’s presence within a system that refuses to recognise it – within this volatile zone of conflict. The architecture of fallahin becomes a time-management tool for postponing demolition orders.

The logic of the Concrete Tent’s envelope should also be analyzed in relation to the broader urban context of Susiya. Both the concrete and the fabric, as I suggest, unfold upon the surface of the earth and play roles in border-making processes. While the concrete delineates the borders of the black space, where practices of eviction and destruction take place, the fabric as a more temporary material delineates the borders of the white space, as it allows the state to perform a gesture of tolerance. However, it does not eliminate the present threat of destruction and removal. Thus, the fabric’s act of veiling-unveiling, or draping-undraping the concrete marks a flickering at the border between black and white spaces. However, this is not to say that if the concrete is completely concealed, the village lies within the white space and is safe; neither is it to say that exposing it puts the village at the instant threat of destruction. In fact, the complex relation at stake is regulated by the space in-between the two materials, which I argue produces a gray zone. The grayness here marks the shifting and unresolved tension between state ‘tolerance’ and fallahin strategies for preservation.

When the space of in-between unfolds upon the surface of the earth, it meets the complex legal pattern of Area C inscribed on the ground. An understanding of this pattern requires drawing back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Israel-Palestine witnessed a shift from the application of international Belligerent Occupation Laws (that were based on different conceptions of security) to the Ottoman Agrarian Land Laws. According to the new adopted laws, any piece of land must be cultivated for ten continuous years in order to come under private ownership. Moreover, if a land is not cultivated for three continuous years, it directly comes under the possession of the sovereign.

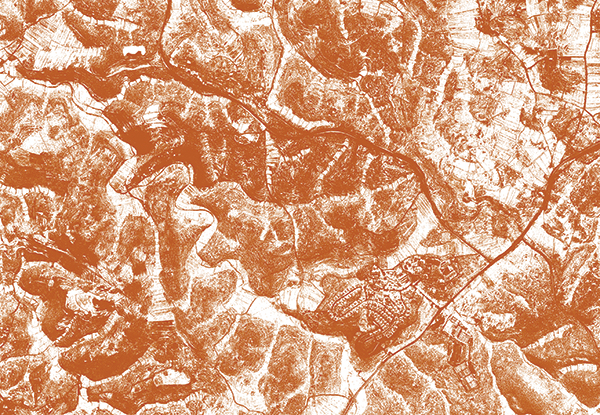

In the late 1970s, Israel based a large scale topographical-mapping and land-registration project on these laws. It was run by the director of the civil department of the state prosecutor’s office, Plia Abek, who started her work by touring the mountains of the West Bank in a helicopter. The project was undertaken from the air, using aerial photometry that would by-pass the problems of doing surveys in hostile terrains. It aimed to define uncultivated lands (which either haven’t been cultivated for three years, or have been cultivated for less than ten years) to which Israel could lay claim. As a result, uncultivated state land existed in a wide range of scales: from large tracts of desert, to smaller islands of rock puncturing the private fields of the peasants. The borders between cultivated Palestinian lands and uncultivated Israeli lands followed a clear topographical logic, but stayed blurry on the ground. The suitable soil erodes down from the summits of the mountains to the valleys, leaving the rocky summits to be declared as Israeli lands – and the cultivatable valleys for Palestinians. Thus, the gray space of Susiya is complexified by the multiplication of internal borders between rocky and cultivated lands that are, in fact, borders between Israeli and Palestinian jurisdictions. However, on the ground, the military orders that are applied to Israeli state lands remained in effect for the Palestinian valleys below and between them. Thus, the materiality of the Concrete Tent here can be understood in relation to the legal pattern of the ground. The harder the ground, the less cultivable it is; the structure must be softer and less permanent in order to be tolerated.

The architecture of the Concrete Tent, as I have proposed in this article, is not a subject of research, but a research tool itself. By analyzing its materiality, I unpacked the agency of fallahin architecture in delineating the borders of the spaces they inhabit. The veiling of concrete by fabric, as an oppositional strategy to the Israeli regulations in Area C, allowed Israel to utilise tolerance as a vehicle for sustaining life in Susiya. Moreover, it revealed how Susiya’s current conflict is rooted in Israel’s adoption of the Ottoman Agrarian Land Laws that in turn have allowed cultivation to become a colonial tool. Today, the whole population of Susiya inhabits the threshold of eviction, living an open-ended story of build-and-destroy.

Resources:

- Eyal Weizman, (2007), Hollow Land, London: Verso.

- Oren Yiftachel, (2009), “Critical Theory and ‘gray space’: Mobilization of the colonized”, CITY, Vol. 13 (Issue 2-3), 246-263.

» Hania Halabi is an architect and a researcher from East Jerusalem who has completed her Masters in Research Architecture at Goldsmiths University of London.