With contributions by Sarah Barrie and Reece Gittins.

Palestinians arrived in Australia mostly through identifiable waves of migration. The first major wave followed the Nakba, the second occurred in the 1960s,*1 and the third and final one was triggered by the displacement of Palestinians from other Middle Eastern countries. The Israel-Lebanon War of 1982 sparked Palestinian migration to Australia and was followed by another surge in the early 1990s when 300 thousand Palestinians left Kuwait during the Second Gulf War.*2 Since 9/11, there has been a considerable decrease in the number of Palestinian-born persons migrating to Australia;*3 a trend that mirrors the Australian government’s increasingly stringent migration policy.

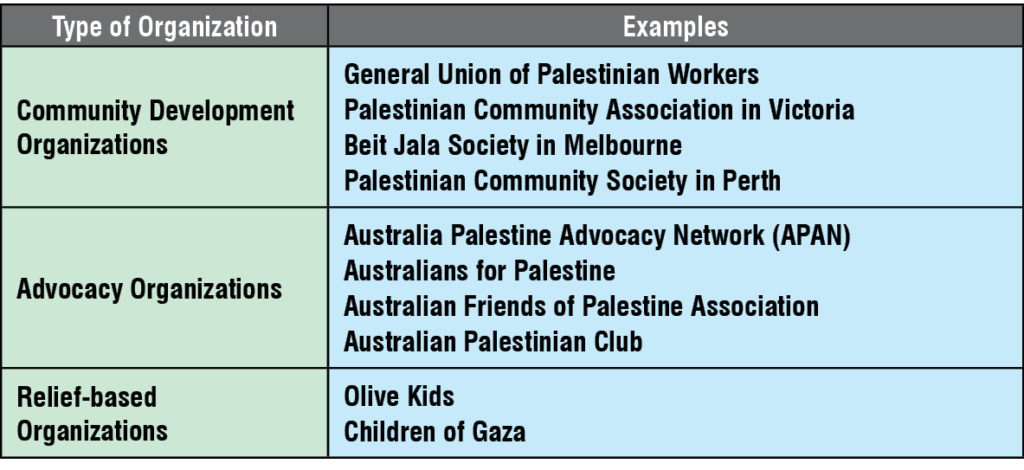

According to the 2016 census, there are 13,293 people in Australia who identify as having Palestinian ancestry, with 2,939 of these born in Palestine. Of those identifying as having Palestinian ancestry, the majority live in New South Wales (62.1 percent) and the next largest group in Victoria (21.4 percent). These figures, however, do not reflect the true size of the community with Palestinian heritage and roots, as many of them hold other passports and may not necessarily identify themselves as Palestinians. We estimate that the actual number of Palestinians in Australia currently sits between 20 thousand and 25 thousand people, with populations concentrated, for the most part, in the metropolitan areas of Sydney and Melbourne. Given this size, there exist several Palestinian organizations that either advocate for Palestinian issues or simply provide a space for the Palestinian community to associate and socialize.

Because being stateless frequently results in a lack of community participation,*4 measures that build on the Palestinian community’s social capital within Australia and encourage community engagement carry particular relevance. The concept of social capital “refers to the specific processes among people and organisations, working collaboratively in an atmosphere of trust, that lead to accomplishing a goal of mutual social benefit.”*5 Social capital is critical in efforts to hold communities together through the development of strong connections, relations, and interests within the community. Social capital may be developed through social networks within a community that aim to ensure that people “feel like members of an identified community that they both contribute to and benefit from.”*6 Social cohesion is a term employed to characterize a sense of community, an attraction-to-place, patterns of regular interaction among themselves, and a sense of trust and mutuality. Social capital is critical to empowering communities – this is, however, a non-linear relationship.

With such considerations in mind, the Embassy of the State of Palestine in Australia held six consultation workshops a few years back that resulted in the establishment of six state-based Palestinian-community coordination committees in New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Victoria, Western Australia, Queensland, and South Australia. These committees provide a forum in which existing Palestinian community organizations can all be represented and, importantly, consult and coordinate meaningfully with one another. The establishment of these committees has facilitated a more unified Palestinian voice that enhances the effectiveness of advocacy work by creating a shared strategic vision amongst Palestinian-Australians. Furthermore, the committees aim to empower Palestinian women and youth and increase their influence on the strategic objectives of Australia’s Palestinian community.

The Embassy of the State of Palestine in Australia supports Palestinian-community coordination committees in New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Victoria, Western Australia, Queensland, and South Australia.

This article highlights some of the key outcomes to date of these consultation workshops. The identified exogenous challenges center mainly around issues of discrimination from the wider Australian public and on the difficulty of competing with powerful Zionist lobby groups. Furthermore, the present lack of an enabling political environment in Australia was cited as a significant challenge.

An important exogenous factor identified and addressed is the discrimination many Palestinians face from Australian media (and some sections of the Australian public) due to their race and/or religion. It was noted that racism and/or anti-Muslim sentiment may make Palestinians less inclined to lobby for Palestinian causes out of fear of alienation or, worse still, reprisal from these elements in Australia.

The Palestinian community in Australia is facing a number of challenges, some of which are exogenous – such as discrimination from the Australian public, the strength of the Zionist lobby, and the lack of an enabling political environment – whereas others are endogenous and include issues of identity, issues surrounding political engagement, factionalism and political infighting, and leadership and technical and professional capacity.

The organizational capacity and the networks (including extensive media networks and political backdoors) of the Zionist lobby in Australia were noted as exogenous factors that make achieving the advocacy goals of the Palestinian community organizations considerably more difficult.

Consultation workshop of the Palestinian community in Sidney.

Meeting of the Palestinian-community Coordination Committee in Brisbane, Queensland.

A picnic held by the Palestinian community in Canberra.

The Palestinian community’s football team is being honored at the Representative Office of Palestine in Canberra.

Celebrating the Palestinian Community Achievers in Sidney.

Canberra National Multicultural Festival 2019.

The political environment in Australia is not conducive to engagement in Palestinian issues and concerns. As there are no Palestinian-Australians in Australia’s federal parliament, this lack of direct representation makes it difficult for advocates to entice parliamentarians to put Palestinian rights on the national political agenda. Other factors that contribute to the prevailing lack of an enabling environment include the relative unimportance of Palestine to Australian political decision makers and the insular, cautious character of Australian politics. Decision makers are inclined not to take any controversial foreign policy positions, lest these decisions impact Australia’s relationship with the United States (strategic) or China (economic).

The endogenous challenges facing the Palestinian-Australian community are at times mutually reinforcing and have played a significant role in impeding the formation of inclusive and effective Palestinian advocacy bodies in the past.

Regarding endogenous factors, the identity of Palestinians living in Australia is critical to an understanding of their community dynamics. Palestinians who were rehomed in Arab states “share with their host populations the Arabic language, the general contours of culture, a common historical experience, and often religion.”*7 The Australian experience is vastly different. Accordingly, one commonality among the Palestinian community in Australia is a shared experience of living in a country that is in almost all aspects entirely different from their homeland.

Palestinians living in Australia form part of the global Palestinian diaspora network that connects groups of people on the periphery through their shared experience of feeling connected to their homeland.*8 Consequently, the dream of returning represents a search for identity as much as it is directed towards a place and results in the formation of an imagined community that aims to maintain a connection to the homeland. For many, however, the lived reality is that of Australia being home.

A central aspect of Palestinian identity in Australia is collective memory, a form of shared experience, the object of which does not necessarily have to have been lived or personally experienced. Comprising a sense of nostalgia associated with a place or time, it is frequently passed on through familial heritage.*9

Australia naturally forms a large part of the identity of Palestinians born in Australia. The conflicting identity of being both a Palestinian Arab and an Australian is further complicated by other forms of identification such as class, gender and religion.*10 In a study conducted by scholars at the University of Sydney, one respondent cited that developing a strong sense of community was obscured by the fact that many Palestinians in Australia come from countries such as Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Egypt and Israel.*11 Nevertheless and importantly, the shared experience of forming an (imagined) community in Australia can be harnessed to form a more empowered and cohesive community with which young Australian-Palestinians can engage.

Identity issues may constrain the potential for capacity building and outreach. The distance from Palestine and Palestinian culture that comes with being part of a diaspora facilitates identity displacement and reduces the drive of Palestinian-Australians to involve themselves in specifically Palestinian causes. Furthermore, it was noted that tensions between religious and Arab-nationalist identities frequently cause friction within the community and undermine attempts at building shared visions and goals. Conflict between Australian and Palestinian identities was also noted as a factor preventing Palestinian community members from deeper engagement with Palestinian issues, a factor that is likely to worsen over time, as new generations of Australian-Palestinians are becoming increasingly detached from their ancestry. This highlights the importance of youth engagement in both, the organizations and the activities of the Palestinian community. Another common identity-related constraint was that the sometimes conservative and patriarchal attitudes among Australia’s Palestinian community may tend to marginalize women and female decision makers.

Among endogenous challenges, the observed lack of political engagement among Palestinian communities throughout Australia is attributable to a number of factors that include community members’ unawareness of the political rights they possess in a liberal democracy, cynicism that stems from the failure of past political processes and from what many view as the intractable nature of the conflict, family and work constraints, and cultural issues such as patriarchal attitudes and a tendency to ignore the voices of young people.

Factionalism and political infighting within the Palestinian community and the tribal nature of Palestinian politics was an issue highlighted in the study, as was the tendency for ego and personality politics to override issue-based politics, impacting the effectiveness of the Australian Palestinian community and its lobby groups.

The final endogenous challenge is leadership, specifically a lack of technical and professional capacity within the Palestinian community organizations. To mitigate the impact of this condition, capacity building programs such as leadership and advocacy training have been conducted. Also, databases of Palestinian professionals have been created to facilitate the exchange of knowledge and ideas, the results of which can be utilized within the programs of the various Palestinian community organizations. Furthermore, democratic and merit-based organizational processes in the committees are designed to elevate the most qualified community members into leadership positions.

To strengthen the Palestinian-Australian community, the coordination committees that were formed as a result of the conducted workshops will engage in community outreach work to increase awareness of Palestinian issues amongst both the Australian public and the Australian-Palestinian community – with Palestinian youth of particular importance. They hope to enhance the feeling of identity in the community that has Palestinian roots and to foster a positive perception of Palestinians amongst non-Palestinian Australians. Some of the activities noted at the consultation workshops include:

- Hosting social events, such as picnics, and commemorations of the Nakba and UN solidarity day

- Conducting Palestinian cultural exhibitions and facilitating cultural programs such as dabkeh and Arabic language lessons

- Performing charity work that helps the wider, non-Palestinian Australian public

- Developing interfaith dialogue

- Reaching out to Palestinian families, given the importance of the nuclear family in educating children and enhancing their knowledge of the Palestinian cause

- Conducting monthly meetings within Palestinian communities

- Creating physical spaces for the Palestinian community to meet

- Establishing a Palestinian community radio

- Campaigns that enhance the Palestinian identity among young people

- Highlighting the stories of Palestinian-Australians in the media

- Organizing special programs that help the Palestinian community cooperate with the Australian community in the pursuit of shared goals, e.g. disaster relief and more.

To foster gender and youth empowerment, programs aim to increase the influence of women and youth within the community by amplifying their voices. Youth engagement in particular is considered essential for preserving the Palestinian identity among new generations of Palestinian-Australians. Proposed activities include:

- Youth development programs such as trips to Palestine through the Know Thy Heritage initiative

- Conducting special meetings with Palestinian youth enrolled in Australian universities

- Gender mainstreaming programs

To facilitate the efficacy of Palestinian advocacy and lobbying, programs aim to promote shared visions and goals through co-operation between key stakeholders in the Palestinian community. Facilitating engagement in the defense of Palestinian rights is considered a key objective in the mandate of the committees. The proposed strategies and activities in this field include:

- Parliamentary lobbying and communicating with Australian MPs

- Attending annual diners with Australian politicians

- Participating in Palestinian cultural exhibitions and promoting Palestinian products

- Civil society outreach

- Media outreach and participation

- Creating focused campaigns on issues that resonate with the wider Australian public (such as children’s rights)

- Training sessions to enhance the communication skills of Palestinian community members engaging in lobbying and advocacy work, including in social media, and to impart knowledge of international law

- Support APAN with a unified and influential Palestinian voice

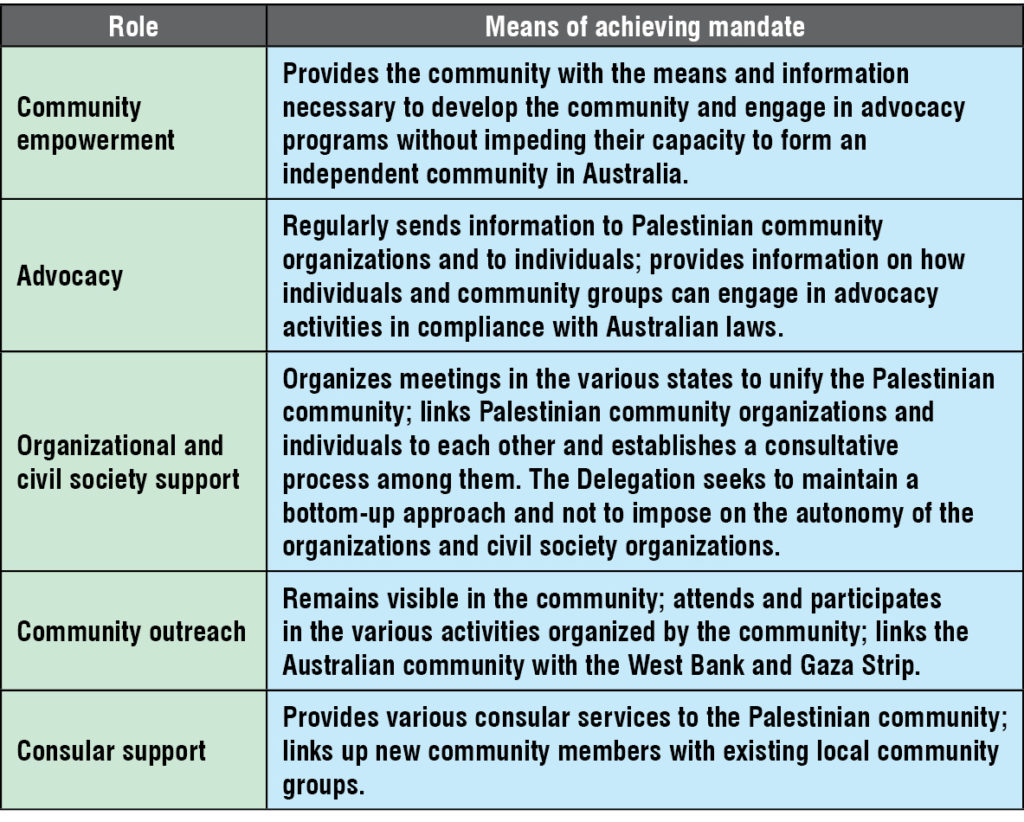

The Palestinian Embassy has a unique role to play in community development within Australia. The core role of the Delegation can be summarized as follows:

*1 Paul Tabar, Politics Among Arab Migrants in Australia (2009), Euro-Mediterranean Consortium for Applied Research on International Migration, available at http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/10793/CARIM_RR_2009_09.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y, p. 4.

*2 Ibid, p. 5.

*3 Department of Social Services, The Gaza Strip and West Bank-born Community (February 2014), The Australian Government Department of Social Services, available at https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/settlement-and-multicultural-affairs/programs-policy/a-multicultural-australia/programs-and-publications/community-information-summaries/the-gaza-strip-and-west-bank-born-community.

*4 Refugee Council of Australia, Statelessness in Australia (August 2015), Refugee Council, available at http://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/1508-Statelessness.pdf, pp. 3-4.

*5 Karen Fulbright-Anderson and Patricia Auspos (eds), Community Change: Theories, Practice and Evidence (2006), The Aspen Institute, available at https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/files/content/docs/rcc/COMMUNITYCHANGE-FINAL.PDF, p. 22.

*6 Ibid 33.

*7 Julie Peteet, ‘Problematizing a Palestinian Diaspora’ (2007), International Journal of Middle East Studies 39(4).

*8 Anat Ben-David, ‘The Palestinian Diaspora on the Web: Between de-Territorialization and re-Territorialization’ (2012), Social Science Information 52(4).

*9 Vijay Agnew (ed), Diaspora, memory and identity: a search for home (2005), University of Toronto Press.

*10 Ibrahim G. Aoude, ‘Maintaining Culture, Reclaiming Identity: Palestinian Lives in the Diaspora’ (2001), Asian Studies Review 25(2).

*11 Jeremy Cox and John Connell, ‘Place, Exile and Identity, the Contemporary Experience of Palestinians in Sydney’ (2010), Australian Geographer 34(3).