I had arrived early for my daily walk with my friend Abed. I took a seat on the stairway leading to Damascus Gate and whiled away the time watching the hubbub below.

“You could not have chosen any better position from which to enjoy the city!” An aged man patronized me from under his long camel-hair overcoat, abayeh, as he dashed past me. I did not recognize the presumptuous voice. “In Amman, they crave to be in your position,” he added without stopping. Before I could identify him he had disappeared into the crowds entering the city gate.

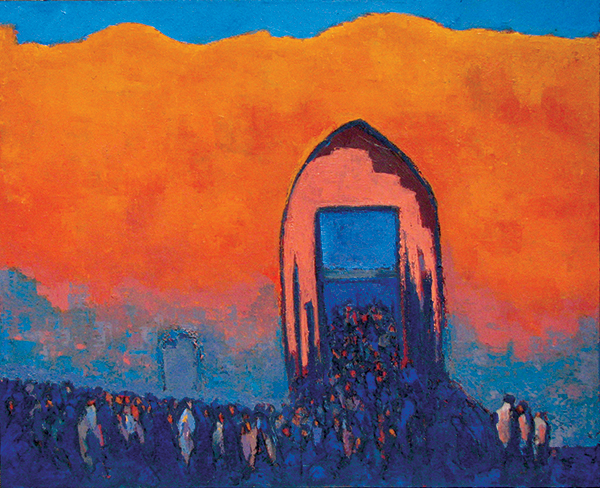

Each Palestinian has his/her favorite gate through which to gain access to al-balad, downtown, which among Jerusalemites refers exclusively to the Old City enclosed within the Ottoman Wall. Herod’s Gate has a welcoming, homey feeling and is used mostly by the residents of the area, as it extends over the eastern living quarter of the city, and the Friday pilgrims. New Gate is used by the residents of the northwestern quarter. Dung Gate is mixed and mainly used by Silwan residents. One rarely uses Jaffa Gate or Zion Gate. Saint Stephen’s gate is the ceremonial gate through which the Palm Sunday procession proceeds into Jerusalem, the gate from which the Nebi Musa procession leaves to go to the sacred sanctuary outside Jericho, and the gate from which the dead are ritually carried, after the prayers in Al-Aqsa Mosque, to be buried in the cemetery outside the eastern wall. It is a favored entrance for drivers celebrating the daily sunrise prayers since it provides an expansive parking lot. Damascus Gate, which is the most beautiful and grandest, is the most favored. People, merchants and pilgrims, crowd its gateway as they enter into the Old City.

Damascus Gate has two gates; one is on street level and one lies directly beneath it. The lower gate is used exclusively as a tourist site and leads to an old Byzantine piazza that lies underneath the upper Ottoman gate.

One approaches the Old City, al-balad, from the Ottoman Gate, which dates from the early sixteenth century. Peasants dressed in their colorful embroidered clothes squat on both sides of the cobblestone street. They come from adjacent Palestinian villages carrying their seasonal produce.

Behind the dilapidated facades of the Mamluk and Ottoman buildings linger layers of ancient history. Underneath the twists and sharp turns of the streets, the planning of Muslim Jerusalem did not stray from the grid of the Roman city plan as revealed in the Byzantine Madaba map. The Umayyad, Crusader, Mamluk, and Ottoman architects used the Roman plan and the various structures lying underneath the city as a point of departure when redesigning Jerusalem.

One enters Damascus Gate as though entering an enchanted cave. One walks on a street knowing full well that underneath it runs another street, from another period. It is dizzying, for the foundations of the Jerusalem homes are deeply rooted in Palestinian history throughout the ages.

The heart of Jerusalem beats in Al-Waad Street. On Fridays, the street becomes crowded with peddlers, beggars, and people on their way to pray. “From God’s bounty give me.” The litanies of the beggars pleading for charity resonate with the staccato advertising calls from the boisterous shopkeepers and peddlers, each pushing his merchandise. Bells from the belfries and calls to prayer from the mosques mix with music from the cafés and shops, and that of the haggling of shoppers and salesmen in a rapturous cacophony. Smoke rises from the grill of the kebab vendors. Through the smoke, Jerusalem exudes an unmistakably oriental air. The vendors, the beggars, and shoppers become figures within a tableau that recreates the magical splendor of Cairo, Baghdad, and Istanbul as depicted in One Thousand and One Nights.

Jerusalem flashes infinite pictures. One closes one’s eyes and its silhouette appears; light and shadow, day and night, sun and moon. Myriad moss-clad domes, like prehistoric turtles, perch on winding alleys, and weathered building-fronts huddle around the majestic Dome of the Rock.

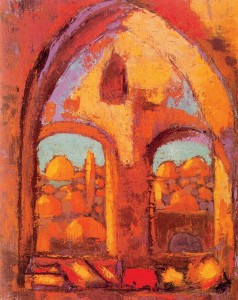

The Cotton Market, the covered bazaar, provides the most spectacular entrance to Al-Aqsa Mosque. The long dark tunnel leads to a staircase in deep shadow. As one stands on the dark landing, the gold of the Dome glistens in the bright sunlight. Climbing the dark steps, one is overwhelmed by the glow outside. Slowly the eyes adjust to the light, shining above one’s head. Through the small open entrance in the giant, leaf-green, painted gate, the deep-green pine tree, the silver-green palm tree, and the blue ceramics that cover the walls of the Dome of the Rock comingle in a sacred symphony of blue, green, turquoise, ochre, and gold.

The simple design and intricate arabesque decoration of the Dome of the Rock is a joy to the eye. But the artistic greatness diminishes compared to the feeling of being in the place where the Prophet Mohammed, may his name be blessed, led all the biblical prophets in prayer before his transfiguration during that pivotal evening Lailet al-Isra’ walMi’raj – The Night Journey.

This is when the doctrines of Islam, related to prayers, are believed to have been revealed; hence the oft-quoted Qur’anic verse, “Blessed be He who transported His slave by night from Al-Haram Mosque to Al-Aqsa Mosque whose environs we blessed.”

To the Holy Rock, Al-Quds, the Muslims first prostrated themselves in prayer. Henceforth, Al-Aqsa Mosque came to be known as the first qibla, direction of prayer, and the third noble sanctuary in Islam.

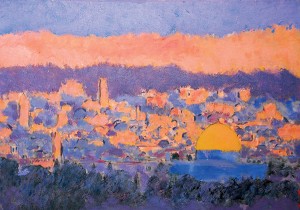

From the top of the Mount of Olives, Jerusalem appears like a mirage at the foothill of the mountain with its glorious minarets and proud steeples embracing the sky, enclosed within the city wall. The houses inside the walls seem sculpted from the mountains. Once inside one cannot avoid the deep sensation that the mountaintops are encroaching upon and enclosing the city from everywhere.

In fact, Jerusalem is built on a number of mountains that surround Al-Waad and Souq Khan al-Zeit streets. There is no escape. One has to climb up and down the stairs whenever one wanders inside the Old City. This kind of stairway, connecting the various parts of the city, is called aqabet (i.e., obstacle). Jerusalem’s labyrinthine alleys challenge us with these “obstacle stairways”: Aqabet Darwish, Aqabet Risas, Aqabet al-Batteekh, Aqabet al-Sheikh Lulu, Aqabet al-Qirami, Aqabet et-Tikyyeh, and Aqabet al-Saraya. All these “aqabat” are stone-paved stairways.

Jerusalem haunts me; sparks of light, images flicker, and a river of sadness flows, flooding the covered passageways embracing memories. Each of us carries an archetypal map of Jerusalem within our heart that corresponds to subjective visual imagery. The clarity, intensity, and proximity to the city determine our mood. Far from al-balad, its markets, alleys, mosques, and churches, one experiences a fall from grace: the Jerusalem blues. Jerusalemites, once severed from their city, languish in nostalgic melancholy (al-huzon). It is our burden, our joy, and our redemption. The vision of Jerusalem is a totalizing multifaceted experience of which each detail is a partial refraction of the whole: an open wound assuaged by its embrace once within the city walls.

Jerusalem alleviates the sense of existential loneliness. It heals and exhilarates. Sometimes, paradoxically, like feeling the Jerusalem blues, listening to Fairuz songs about Jerusalem, and feeling better. On another level, when I take a walk and stroll downtown (al-balad), I am aware that I am opening myself up to the archetypal spiritual energy of the Holy City, which rises up and completely fills me, transforming my own energy, so that I at some point incarnate and actually become Jerusalem, overflowing my body boundaries and becoming one with the universal spirituality it exudes. Jerusalem is my source of inspiration. I am inside her. She is outside me. A writer and a painter, I alternately move between the two forms of expression. To write or to paint is the question.

I walk the flagstone street in Aqabet al-Qirami, past the last surviving shrine of Al-Qirami. I watch a pious lady lighting a candle and slipping it through the metal rails of the shrine window. I try to visualize the Jerusalem of the eighteenth century. I hearken to hear its echoes. Was the road paved with flagstones then? Did the streets have lights? I see my great-grandfather fumble in the shadows, cane in hand in his colorful brocaded gown and green turban on his way to the dawn prayers at Al-Aqsa Mosque.

♦ As I stand immobile facing Damascus gate, the hubbub of life within the Old City is conjured involuntarily into my mind’s eyes. The existential perception of and proximity to the Ottoman wall is cognitively meaningful in relation to the city as a whole. The perceived part of the wall is a metonymic displacement of the whole. Each neighborhood, street, minaret, and steeple is a metaphor of the holy city.

I peer at the distant horizon through a covered passageway cascading past Aqabet al-Khaldieh towards Al-Waad Street. I focus my gaze on the nearby homes. The two cupolas on top of the adjacent house bathe in light. Behind the cupolas, a bluish mass of shadows cascade noiselessly on the other rooftops. In the distance, beyond the domes, the yellow cupola of the Dome of the Rock shines under the golden sky of Jerusalem.

Colors, sounds, and smells combine to give the city its unique character. Each neighborhood has its own distinctive scent. Even before one enters Zalatimo Pastry Shop, the smell of clarified butter and honey signal that one has arrived. The sweet aroma reaches one’s nose from far away and is easily distinguishable from the hundreds of smells that saturate the commercial thoroughfares.

The first scent that assails one upon entering Damascus Gate, immediately after walking down the stairways, is that of the toasted coffee from Izhiman’s Coffee Shop at the juncture of Al-Waad Street and Suq Khan el-Zeit. The aroma of freshly roasted and ground coffee dissolves into that of freshly baked bread and sweet, crunchy, warm, round ka’ek and toasted sesame seeds that soon merges with the pungent aroma of pickles, olives, and cheese in Al-Hidmi Grocery. Gradually the smell of pickles gives way to fragrant rose water. Deep beyond Suq Khan el-Zeit, the Spice Market enthralls with Jerusalem’s bouquet of cardamom, coriander, cloves, cinnamon, cumin, fenugreek, nutmeg, pepper, saffron, turmeric… The lofty quarters of Jerusalem are redolent with incense. Musk oils and perfumes from Muslim sanctuaries and myrrh and frankincense from the Christian monasteries and churches rise from the city into a misty fragrant haze.

From the Mount of Olives at sunrise, a lavender cloud hangs over Jerusalem. The rising sun quickly dissipates the deep purple morning mist into deep blue that by the early morning hours turns into cerulean blue. The same panoramic vista abounds with religious symbolism. In this image, sacrosanct to every Palestinian, the houses pile high, one on top of the other, behind a great wall that surrounds the city. In the depiction Jerusalem is a still life; a stone sculpture of domes of various shapes and volumes on top of squares punctuated by minarets, belfries, crosses, and crescents. The golden Dome of the Rock dominates the picture. To its left, the lead dome of Al-Aqsa Mosque hides behind cypress trees. In the middle of the city rises the dome of the rotunda that enshrines the Holy Sepulcher of Jesus.

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher is a complex building that contains numerous churches. Roman Catholics, Armenians, and Greeks share rights of access and partition the space – within and without, including the roof – with the Copts and Syrians.

The Saturday of Light is the most joyful ceremony. On this occasion that commemorates Jesus’ resurrection, Christians of the Eastern Churches crowd into the Holy Sepulcher. Each person stands within the boundaries of his/her own sect. People stand for hours waiting for the eruption of the Holy Fire through a small window in the tomb of Jesus. At noon, the electric lights are dimmed. The Church soaks in shadows and a hushed silence hovers. Myrrh and frankincense drown the cavernous rotunda. The bells begin to ring rapturous religious melodies. All of a sudden the light flashes in the darkness. In the wink of an eye the light moves from candle to candle throughout the Church and the pilgrims become a procession of light. The aroma of burnt beeswax saturates the air. The walls of the Church resonate with traditional Eastern liturgical chants, and the bells continue to pound. Young men, lifted on shoulders, pass the flame among the awestruck crowd. Amidst the ululation and singing, the Holy Fire, in candles and lanterns, floats overhead from hand to hand to be carried to the Eastern churches all over the earth. Holy Saturday is a Jerusalem symbol.

Like in a kaleidoscope, the Jerusalem images combine and recombine to form a repertoire of iconic images with seasonal, religious, and ethnic ritual character. Each of us carries our own Jerusalem in our heart.

The ubiquitous picture of Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives is found in the living room of every home throughout Palestine, in Jordan, and in the diaspora. On the opposite wall, beautiful Arabic calligraphy, a verse from the Qur’an, hangs in a golden frame. In other Palestinian homes hang other pictures opposite the picture of Jerusalem: icons of the Virgin Mary carrying in her arms the baby Jesus, or a cross or Saint George thrusting a spear deep into the dragon.

♦ Jerusalem has and continues to be the center of strife. The rise and fall of the various civilizations have left infinite traces. Their remains were used as elements, absorbed and assimilated in the cultural ethos of the nations that followed. The facades of the houses, palaces, theological colleges, mosques, monasteries, churches, temples, zigzagging streets and alleys are silent witnesses to its central position as a crossroad of Judeo-Christian-Muslim spirituality.

The picture of Jerusalem, with its soft texture and its shining surface is not a still life, a city of stones. Of paramount symbolic significance, the image is of iconic value. It is the source of our being, pulsating life and warmth. It is our wound and cure. The picture of Jerusalem aligns us with a spiritual mood and energy and helps us connect to the ideas and energies it is associated with. It helps us achieve states of clarity, focus, and/or calm and helps us connect with God. Palestinians severed from their homeland endure the trauma with nostalgic melancholy. The iconic image is the palliative balm pending the return home.

The words of my friend, Abdulrahman Hashem, from Amman, eloquently sum up the feelings stirred by the first sighting of Jerusalem from Mount Scopus. “Jerusalem is the echo of a mother’s voice in the ears of her baby. It is the womb of humanity.”

Jerusalem floats as a vision of gold. Yellow ochre, cream, grey, pink, and red bounce off the meleke and mizzi stones and give the Holy City a magical luminescent painterly quality. Sunlight on the cream-colored limestone edifices gives them a golden ochre hue. The light reflects off the facades of sumptuous Mamluk and Ottoman edifices, dissolves the spectrum of lustrous colors, and soaks Jerusalem’s labyrinthine alleys in a haze of translucent amber honey. Shades of pale blue lurk beneath the edges of the stairs, navy blue in the gaping tunnel-like doorways that becomes deep purple piling under the cavernous covered passageways. The glow of the daylight yields to night. By the time the muezzin calls for evening prayer, the stones drown in soft grey-blue under a lapis lazuli sky. By night the domed roofs huddle together under mysterious deep-purple-blue to be dispelled by the golden ochre light of sunrise.

Jerusalem remains a mirage veiled in mystery… a dream committed to a vow of silence. My vision of Jerusalem is intensely personal. Nostalgia, longing, and an unfathomable sense of loneliness envelop Jerusalem in a halo of huzon – sublime melancholy; a bittersweet refrain whose echo reverberates behind every step in Jerusalem. The energy overflows into art. The sensation coalesces into words that dissolve into pigments of light and shadow. The image solidifies into lines, volumes, and color. The feelings become a painting.

Strange how one completely buzzes with creative energy while being the creative field, the afterglow resonates and then one must renew and re-engage with Jerusalem in order to become creative energy again. In Jerusalem timeless awareness requires time. Time requires timeless awareness. The alternative, far from Jerusalem, is the dark nihilistic abyss or unremitting, unbearable anxiety: the Jerusalem blues.

» Dr. Ali Qleibo is an anthropologist, author, and artist. A specialist in the social history of Jerusalem and Palestinian peasant culture, he is the author of Before the Mountains Disappear, Jerusalem in the Heart, and Surviving the Wall, an ethnographic chronicle of contemporary Palestinians and their roots in ancient Semitic civilisations. Dr.Qleibo lectures at Al-Quds University.