Most probably, everyone in Palestine has heard about Ismail Shammout, the son of Lydda, who, at the age of 18, during the Nakba, was forced to flee from his birthplace and take refuge in a refugee camp in Khan Younis in the Gaza Strip. Today, he is one of the most renowned Palestinian artists. Why is Ismail Shammout considered the pioneering Palestinian artist? Why is he different from others? What art did he create? And what did his art achieve?

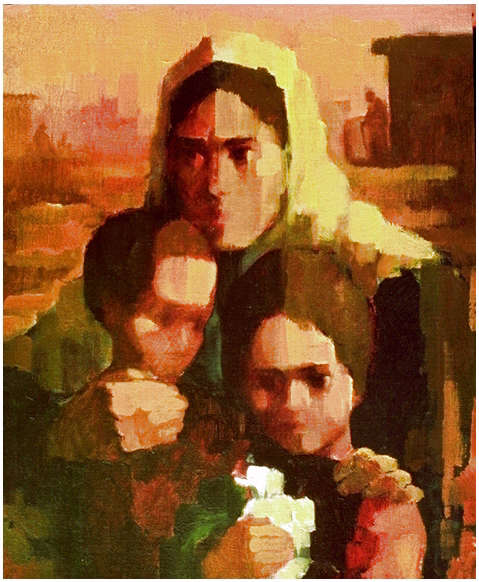

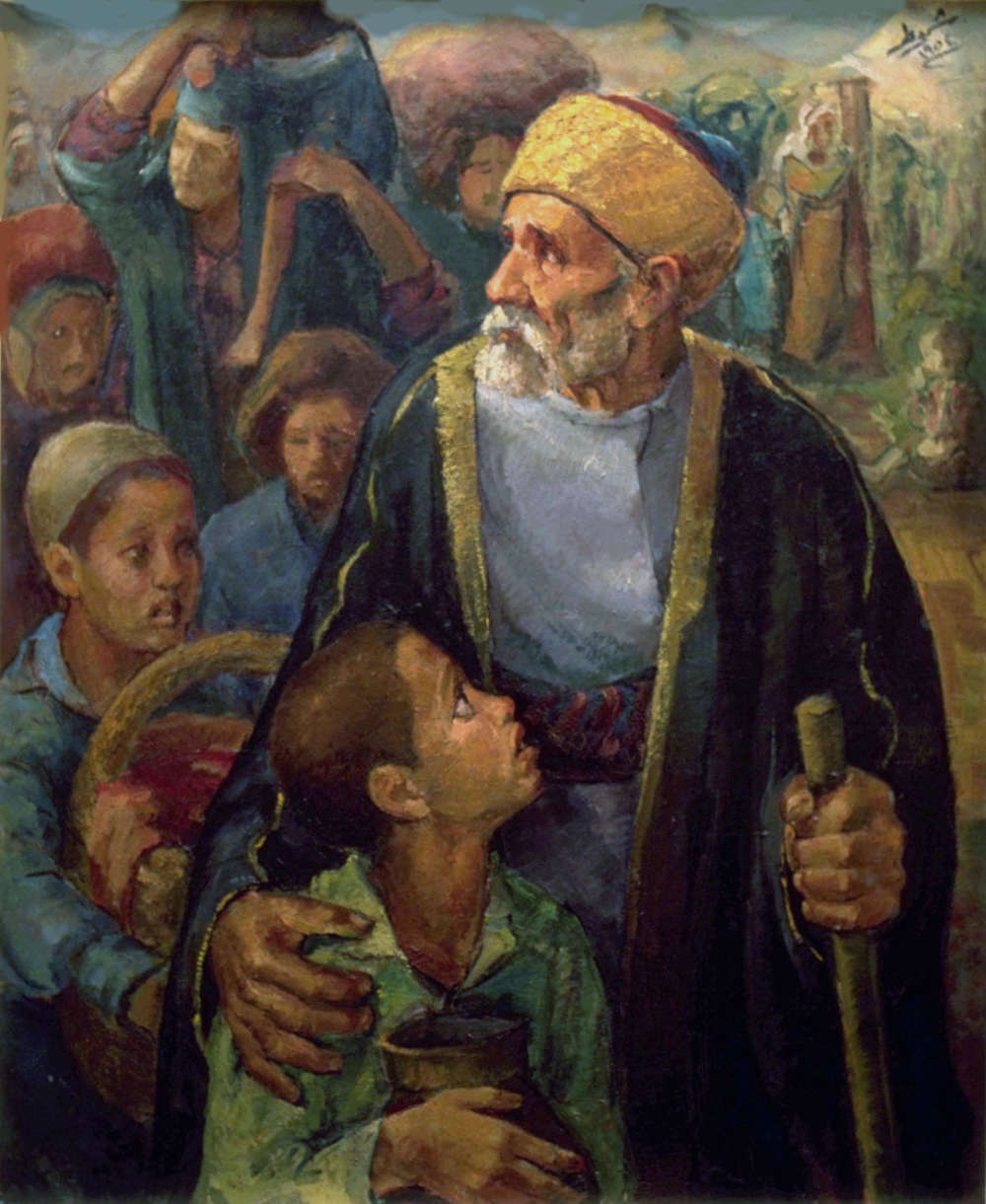

Even as a child, Ismail was very talented and had a strong belief in the power of art. For this reason, and despite difficult socio-economic circumstances, he left his family and the camp in 1950 to pursue his studies in art at the College of Fine Arts in Cairo. Throughout his studies, he worked perseveringly to express and document the tragedy of the Nakba that had so deeply affected him, his family, his town, and his people. He transformed his painful reality into a potent symbolic icon that reflects important aspects of the Palestinian nation-building process and illustrates the history of its most recent development since the Nakba. Studying the titles, dates, and the mood and spirit of his paintings offers a glimpse into how the Nakba was perceived and thus a deeper understanding of the cause of the Palestinian refugees and the mystery behind the strong insistence on the right of return, even after 70 years of exile. Shammout’s documentation of the Nakba is of utmost importance in preserving and imprinting the images of the reality of what happened in 1948 on the minds of future Palestinian generations. In the painting Where to? (plate 1) Shammout records the tragedy as he lived it, how people left their homes, taking nothing with them except their children, thinking that they will be back (plate 2). Any one of the young boys in Shammout’s paintings could be a portrait of himself, and they represent all the youngsters who had to flee with their parents and grandparents. In July 1954, these two paintings were among his graduation exhibition, in which he exhibited more paintings of the same tragedy, together with some artworks by his colleague then and later his wife, Tamam al-Akhal. The fact that the exhibition was inaugurated by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel-Nasser earned Shammout a good reputation and provided him with great encouragement. Thus, he traveled to Rome, where he joined the Academy of Fine Arts.

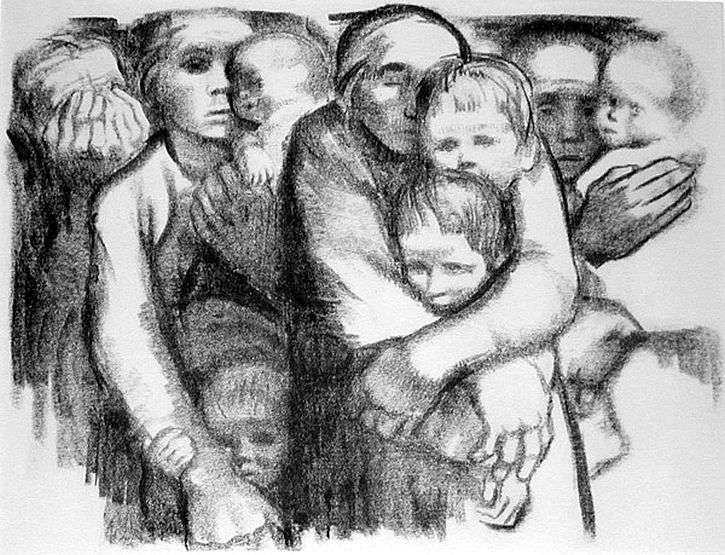

Yet this appreciation does not sufficiently reflect the respect he earned among artists and critics of the historic international art scene. Similar to artists of the German Expressionism movement, Ismail Shammout succeeded in expressing his own emotional experience in order to evoke moods and ideas, document calamities, and expose injustice. In fact, Shammout’s works bring to mind those of Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), a German artist who depicted the effects of poverty, hunger, and war on the working class at the turn of the nineteenth century and during the two world wars. In 1922, Kollwitz noted, “My art has purpose. I want to be effective in this time in which people are so helpless and destitute.”i Both Shammout and Kollwitz believed that art has a mission as a powerful agent that can have an effect on society; art is superior to agony and calamities, prevails over injustice, and thus can serve as a beacon that points us towards an improved human condition and a better future.

Both Shammout and Kollwitz employ realism in their works. They depict historical events and document incidents as they happened, without exaggeration. Both excel in expressing subjective emotions and personal responses, showing the suffering of people affected by human tragedy. They evoke strong emotions in the viewer because their artworks are simply breathtaking. Their use of lines, light, and shadow – in some cases color – captures the spirit, mind, and heart of the viewer, making their works unforgettable and effective in the long run.

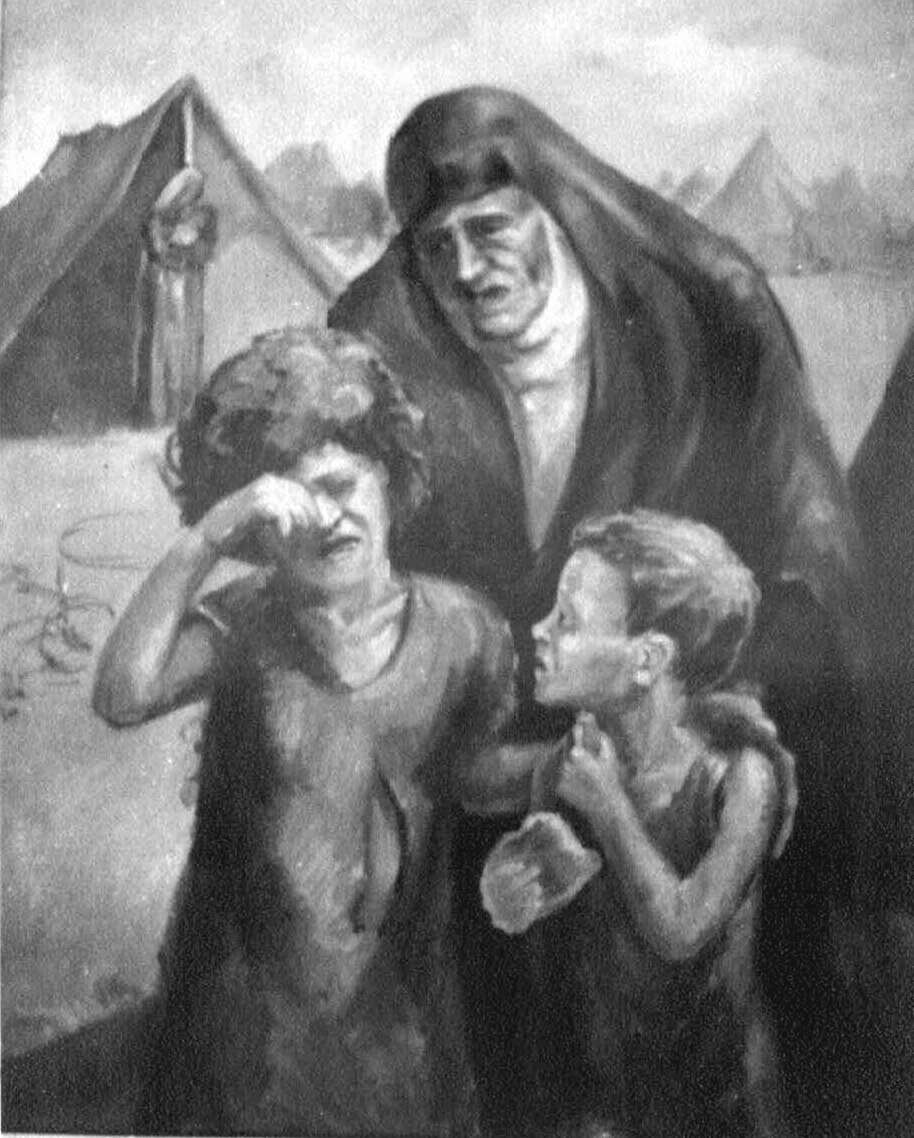

Great empathy for the suffering of women and children is conveyed by the work of both Shammout and Kollwitz. After World War I, Kollwitz created Mothers (plate 3) in 1919, and The Survivors (plate 4) in 1923, both featuring desperate mothers holding their surviving children. In 1952, following the Nakba, Shammout painted Where’s my father? (plate 5) showing two children asking a grieving grandmother about their absent father. In 1967, following An-Naksa,ii Shammout painted My Children (plate 6), which depicts an alert woman tightly holding her two children as if she is fearing something on the horizon. And in 1976, Shammout produced several paintings that represent the Tel al-Zaatar Massacre (plate 7). When comparing these artworks, one cannot disregard how similar they are in depicting the deep sorrow and pain of the women and the fear and confusion of the children. Yet, in these same works one can also feel the steadfastness of the women – mothers who are strong enough to hold their children and continue to live for the sake of their children’s survival. It is worth mentioning that Kollwitz had two sons, the younger of whom, Peter, she lost in October 1914 on the battlefield in World War I, while Shammout lost a young brother while fleeing from Lydda during the Nakba. Both experienced the pain and sorrow of death during war.

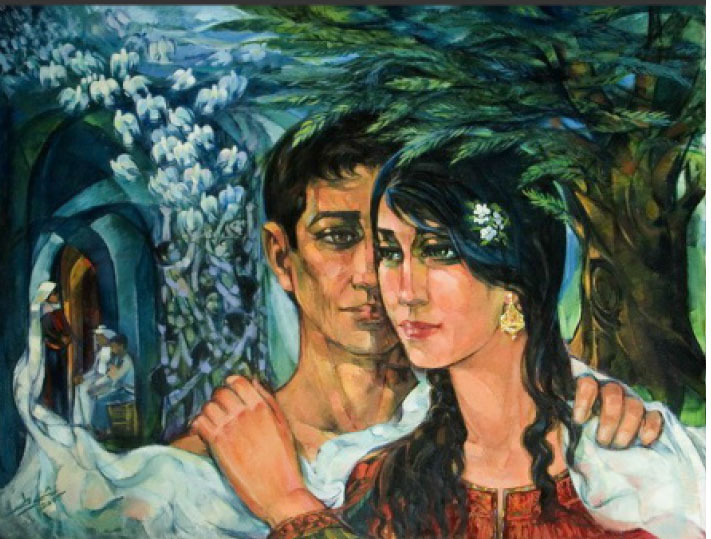

Throughout more than forty years of creativity and production, Shammout as well as Kollwitz depicted scenes of people in battle in dramatic and powerful ways, such as in Massacre of Deir Yaseen (plate 8) by Shammout and Outbreak from the series The Peasant War (plate 9) by Kollwitz. Their works documented important historic tragedies that neither photographs nor news could document. But at the same time, they also celebrated love, joy, and beauty, such as in one of Shammout’s latest works, Love and Dreams (plate 10), and Kollwitz’s Mother with Child (plate 11).

Plate 7

Plate 8

Plate 9

“The most noble of goals are those that take human beings as their focal point and strive to release them from injustice, giving them life and beauty, and opening new horizons for future aspirations.” Ismail Shammout and Tamam al-Akhal

Plate 10

Above all, I believe that their artworks are remarkable and immortal because they both succeeded in expressing what was beyond the tragedy and beyond history; they excelled in capturing the emotions, the passion, and the spirit of the people, which makes their masterpieces effective and valid for any afflicted nation no matter where or when.

Plate 11

For additional information or to view more works of Ismail Shammout or Käthe Kollwitz, please visit http://www.ismailshammout.com/

and http://www.kollwitz.de/en.

i The Trout Gallery at the Art Museum of Dickinson College, Käthe Kollwitz exhibition brochure, Pennsylvania, 2017.

ii The occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 1967.