“It’s the end of the world as we know it. And I feel fine” (R.E.M., 1997)

As the Palestinian National Authority prepares to cope with the possible spread of the CoViD-19 pandemic throughout the West Bank, all sectors of Palestinian society are mobilizing to face an unprecedented national emergency. Of course, the Palestinian people have been living a series of emergencies for the past 70 or more years. But these were man-made and part of the struggle with Zionism and settler colonialism, much different from the current crisis that is shaping up as a confrontation between nature and humanity on a global scale. In all those episodes, the shocks to society and economy were no less significant than those to human life, and often persisted well after the dust of war had settled.

Nevertheless, Palestinian social discipline has been growing (though perhaps not as fast as the virus is spreading), uninformed panic avoided, and general trust in government leadership so far has been unusually widespread. Sure, experiences of intifadas, wars, and constant confrontation with Israeli settlers and authorities have taught the Palestinian people a thing or two about social solidarity, adapting to rapid and unexpected change, and resilience. And our healthcare system has been re-tooled regularly to deal with war and emergencies. Thus, however much the epidemic spreads in Palestine in the coming weeks, and however well the healthcare system can bear the burden, we can hope that Palestine has an edge over other countries in its ability to pull together as a people and do what must be done to weather the storm.

While the public health aspects of this crisis are perhaps partially in the hands of fate, the shape, if not scale, of the socio-economic impacts and outcomes can already be envisaged, and possible responses considered. Indeed, any analysis of the Palestinian economy can only resort to terms such as vulnerable, fragile, shocks, volatility, and dependency. Economically speaking, we have been here before, with the waves of Israeli invasion and closure of the West Bank and Gaza Strip after 2000, which resulted in a precipitous fall in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the West Bank, by 40 percent over three years, and the impoverishment of tens of thousands. By 2003 the Palestinian economy was two-thirds the size it had been in 1999, and recovery from that low point took many years and was complicated by the collapse of the PNA’s administrative capacity, political and social division, and the halt of donor aid and Israeli tax transfers. It was only by 2010 that the economy had regained its pre-2000 level of output, employment, and relative stability.

In the current crisis, we may well be facing losses of this magnitude, though in the space of less than a year. However extensive the shutdown of the economy might have to be, it is possible that some of the most economically harmful dimensions of previous crises may be mitigated by a well-functioning PNA, social solidarity, and discipline. While donors may at best maintain recent levels of external financial resources needed to fund government operations in Palestine, a full-blown epidemic will call for much more. Indeed, were the crisis expected to be short-lived, the resilience of the Palestinian society and economy is such that a fast recovery could be possible, making up for the lost income of the current slow-/shutdown. The shocks of the second Intifada came in waves over three years. Current expectations point to at least a two-month duration of the state of emergency before normal economic activity may start to pick up again. In the meantime, measures to combat the virus through geographic quarantine (Bethlehem, Beit Jala, and Beit Sahour) and sectoral closure (tourism, education, and most branches of trade and services) have already curtailed output, consumption, movement, and investment across the West Bank. A (best case) economic impact scenario would certainly entail a moderate decline of Palestinian GDP in 2020, as opposed to a sharp decline in case of a more extensive and prolonged fight against the virus.

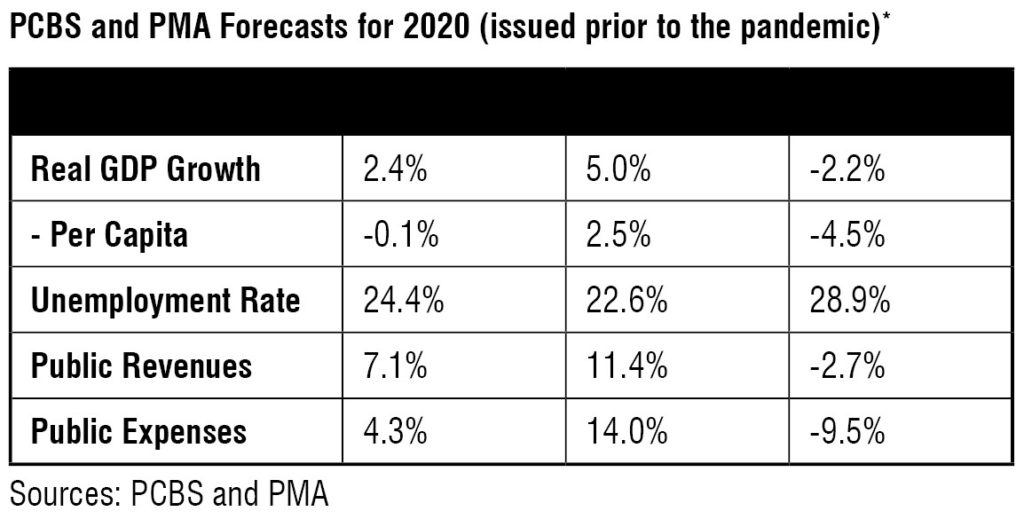

The current expectations and state of emergency (two-month pandemic) at best will result in an economic situation similar to the pessimistic scenario in the economic projections issued by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) and the Palestinian Monetary Authority (PMA) for 2020 (see the table below). The scenario envisages a political/security deterioration that would result in a 2.2 percent decline in real GDP, and a 4.5 percent decline in per capita income, with an increase in unemployment and public deficit. That means that a recession of limited impact (by whatever cause) would shave at least 5 percentage points off the previously expected performance for 2020, equivalent to less than $1 billion.

Hence, while the reasons for reversal might be different than those assumed by PCBS/PMA, we cannot escape a recession (at best) this year. Its scale will be determined by Palestinians’ collective ability to minimize the impact of the pandemic and to spread the economic losses so that nobody is left behind in efforts to buffer the severity of the shocks over the next months.

The scale of the upcoming recession in Palestine will be determined by the collective ability of Palestinians to share the economic losses so that nobody is left behind, as efforts are being made to buffer the severity of the inevitable shocks to our economy.

The multiplier effects of the crisis on consumer sentiment and preferences are already depressing private demand for goods and services, including imports. Economic supply has also been hit as economic establishments are being shut down in an attempt to control the spread of the virus, and employees are being laid off, particularly in small and medium enterprises (employing 90 percent of the labor force). The impact of the inevitable global recession/depression has yet to reach Palestine, and it will further depress Palestine’s economic performance. However, this is a crisis whose shape and scale are unpredictable, globally and in Palestine, and any projection of just how bad it could get can only be a guesstimate. However much we may succeed in evading the worst of the CoViD-19 impacts, manage to mobilize financial resources to combat the disease efficiently, and be able to shore up a battered private sector economy – a mild recession in the single-digits looks increasingly unlikely.

Could the economic impact be as severe over only a few months as the shock of eighteen years ago? Yes, it seems, regrettably, that the economic retraction in one year could be as bad as the experience over three years during the second Intifada if Palestine is not able to preempt the worst-case scenarios we are witnessing throughout the world of a generalized outbreak and near-total lockdown.

The ability to recover from the economic impact once the health crisis is over will depend to a large extent on the flow of aid and support from abroad – unless other means can be generated to finance public expenditure and support the economically most vulnerable, small and medium businesses, and NGOs.

The economy today may be more structurally sophisticated than before, as safety nets, financial intermediation, and liquidity can provide more coping tools and the government can provide greater security. But government finances were already strained before the crisis. Some 150,000 Palestinians depend on jobs in Israel (which will now be cut by as much as two-thirds) to generate income for the poorest families, and the sector of our economy in which many livelihoods depend on trade and services activities is currently shuttered.

So the financial resources to meet the immediate challenge of pandemic mitigation and the longer-term challenge of saving a faltering economy are going to be hard to secure in the coming months. Indeed, the PNA does not have recourse to the sort of fiscal stimulus measures that most countries are enacting, in the trillions of dollars. The first measures announced by the PMA to delay debt repayments and the government’s agreement with employers and workers to not release employees, but to only pay half of the March/April salaries, show that all parties have begun to cooperate to mitigate shocks and smooth adaptation to this new situation. But it remains to be seen how much of the burden of the recession private sector employers can bear (and for how long) without having to lay off thousands. So much more will need to be done if the pandemic is prolonged, or recurrent, if we are hoping to avoid a double-digit recession. Only through extraordinary measures might international financial institutions such as the IMF be obliged to treat Palestine like other vulnerable developing countries facing the crisis and extend emergency loans to the PNA to enable it to keep the economy open.

In immediate measures to deal with the economic crisis, the PA has announced that debt payments are being postponed and agreed with the private sector not to dismiss employees but to pay only partial salaries for the months of March and April.

Once this totally unexpected crisis is behind us, many things will have to change both globally and in Palestine. The aftermath of this pandemic will affect the way we conduct business, what and how much we consume, and how we interact socially. Some commentators have already pronounced this crisis as the death knell of the last thirty years of globalization. It is not surprising that it took a global crisis of this magnitude to challenge humanity’s hubris and complacency about its superior status, its disregard of nature and ecology, its materialistic way of life, and people’s assumptions about the conduct of social relations. In Palestine too, this crisis will have an impact like none other we have lived through, but thankfully always survived.

In the midst of the 2008 global financial crisis, a senior US presidential adviser, advocating a strong fiscal response, famously said: “You should never let a good crisis go to waste.” It can only be hoped that we all will draw some lasting lessons from these difficult times – about our way of life and consumption, public hygiene, social cohesion and interactions, and our relationship with Mother Nature.

Our way of life will not be the same after we emerge from this crisis, affecting how we conduct business, consume, interact socially, and deal with nature. It might not all be for the worse!

In the case of Palestine, so closely intertwined with the virus conflagration in Israel, we might have hoped that the next months would teach us, or Israel, something new about our apparently inescapable economic relation – between 40,000 and 70,000 Palestinian workers in Israel have been allowed to stay in Israel for at least a month, with public health and livelihoods trumping security for the moment. But if first reports of Israeli treatment of those workers are accurate, whereby employers have neglected to provide decent shelter, and cases of infected workers are being deported to Palestine, maybe some things won’t change that easily.

The end of the world as we know it? Maybe that’s not such a bad thing!

*The baseline scenario assumes continued circumstances as those that prevailed in 2019, and the optimistic growth scenario assumes improved political conditions.