The exact date of the birth of Jesus Christ in the Grotto of the Nativity is not known, but there are historical indications that the grotto was localized in the middle of the second century AD. The exact location was agreed upon in the third century AD.

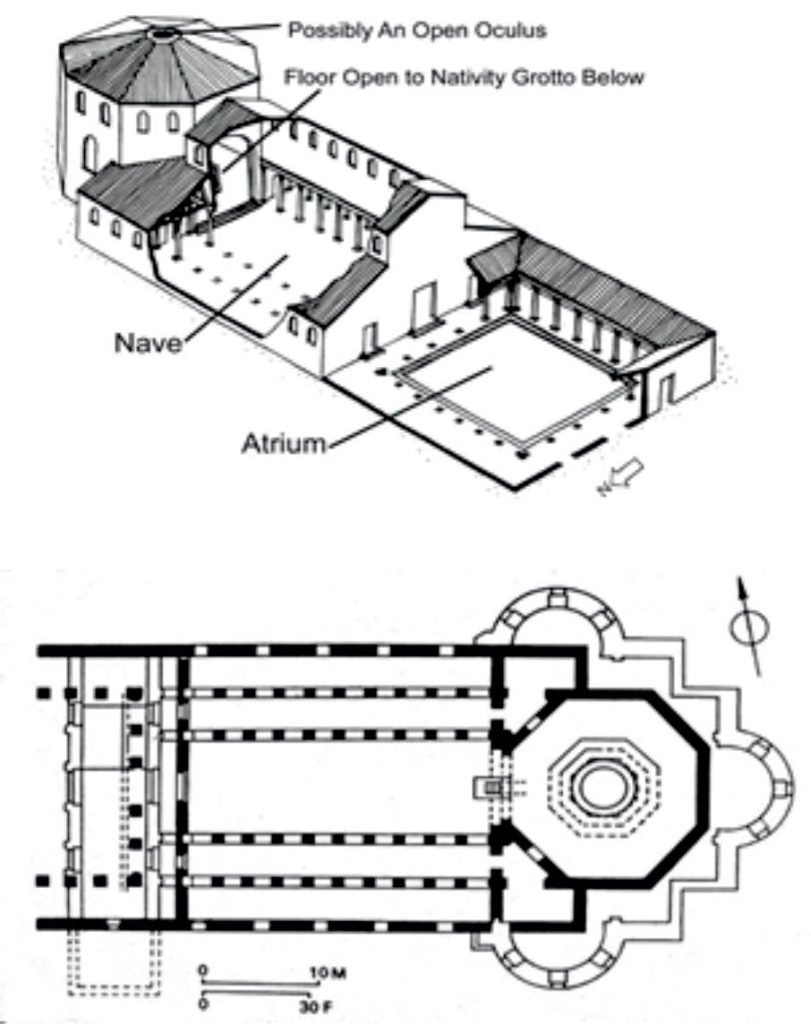

Emperor Constantine built a basilica over the cave to provide a sacred passage to the holy site. Work began in 327 and continued until the year 333 AD. The basilica was officially inaugurated on May 31, 339.

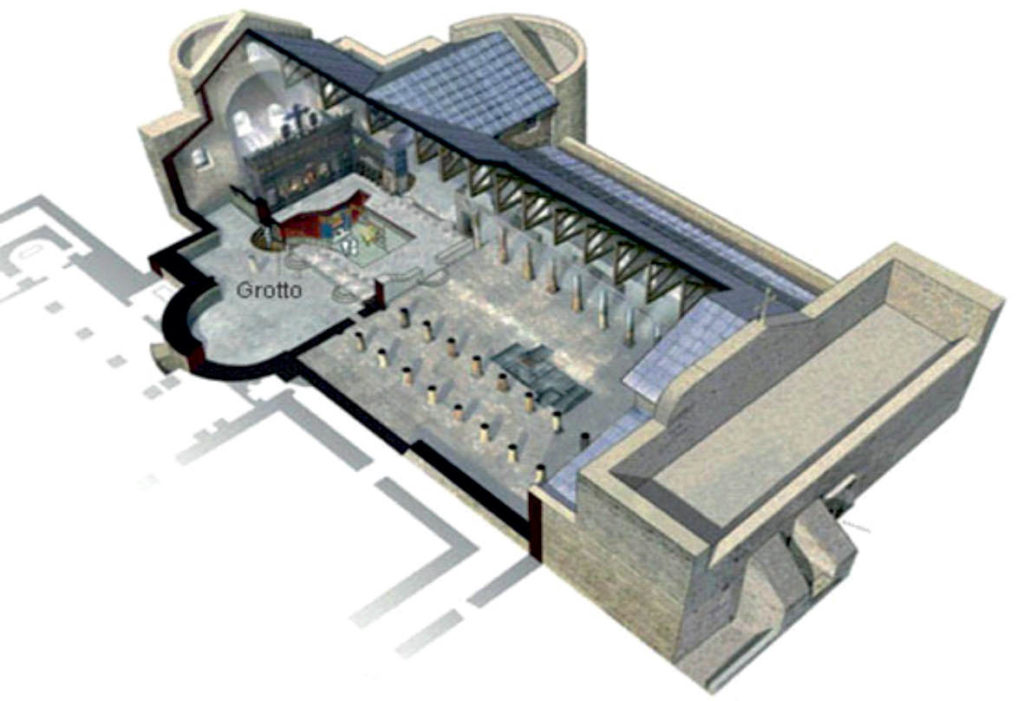

The five-aisled basilica’s wide middle aisle ends with steps leading to the platform of the altar (bema), above the cave, within a raised memorial octagonal structure. Abundant areas of floor mosaics, seen even today, contain geometric designs, flora, fruit, various types of birds, and some writings, including the name of Christ in Greek. The size and the artistic level of the floor mosaic reflect the distinctive position of the church and its central symbolism. The mosaic floor is located approximately one meter below the current church level as seen in the original examples that are present today. The walls of the church of Constantine were most likely dressed from the inside with marble slabs.

The church was burned and destroyed during the Samaritan revolt in 529 AD, as evidenced by the traces of the fire discovered on its floor. Later, Emperor Justinian ordered that the church be rebuilt in all its magnificence and grandeur. The basic structure of the present church is the same as that built by Emperor Justinian. Recent studies conducted prior to the current restoration work confirmed that the walls of the church, the columns, and the architrave (Lebanese cedar) all date back to the time of Justinian. It is certain that the present church was built before 560 AD, the year of Justinian’s death.

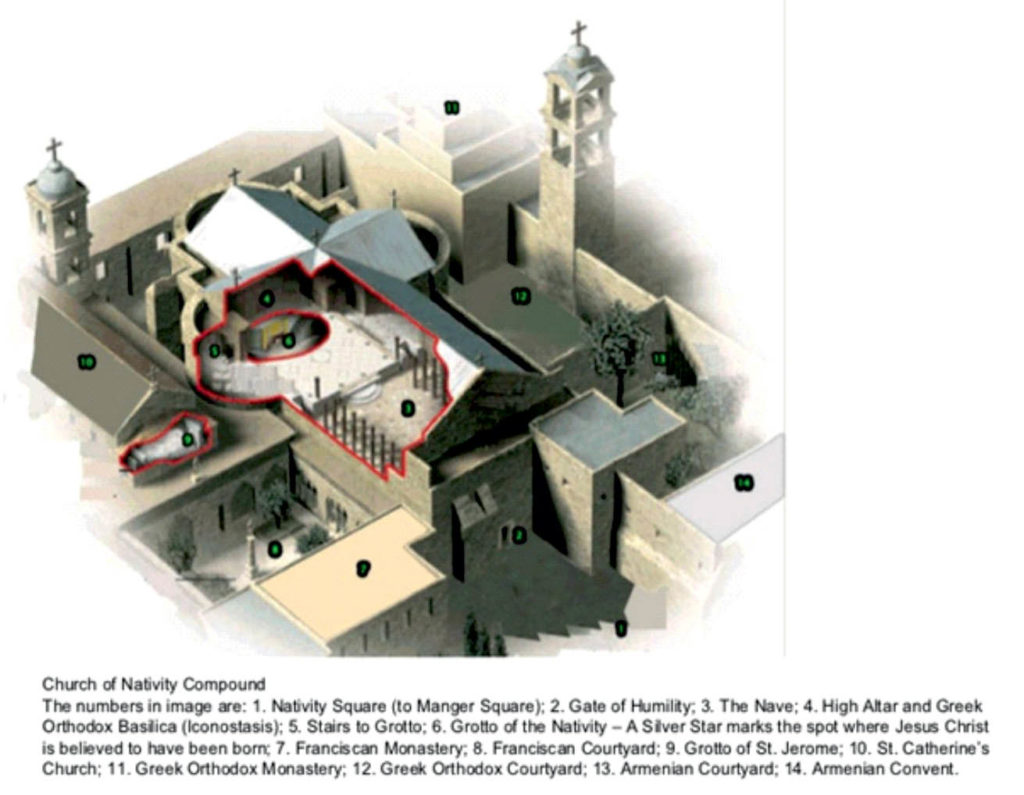

Blocked with stone walls today, the original church commences with three large gates, the largest being the middle gate, which was made smaller twice: the first time during the Crusader period and the second during the Ottoman period. The small door (referred to as the Door of Humility) leads to the narthex (the entrance hall) and then to the five-aisled basilica. The ceiling rests on 50 columns, each rising to 5.40 meters (including the base and the capital). All the columns were made from local pink limestone. The capitals were decorated with gilded Corinthian motifs. Above the columns are some beautifully decorated wood architrave with friezes of flora and Corinthian motifs, and geometric forms dating back to the Justinian era. The outer walls of the main building were constructed of well-dressed local limestone blocks, each up to one meter long and up to 40 centimeters in height. The church’s saddle roof was covered from the outside with lead sheets, almost as it is today. Before the Crusaders’ intervention in the church, the interior ceiling was also decorated. With time, all the wood of the roof was replaced. Today, the oldest piece of wood in the roof structure dates back to the year 1164 AD. Some of the wood in the ceiling dates back to later periods – sometime between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries.

A huge baptismal font, from the Justinian period, was found in the southern aisle, made from the same pink stone as the columns. Inside the large font, another smaller baptismal font was recently discovered. It was made out of a late Byzantine capital that was carved out in order to create a basin. The Justinian font has an inscription written in Greek: “For the memory, comfort, and forgiveness of the sins of those whose names God knows.”

The church survived the Persian invasion (614–628 AD), during which the Persians, in alliance with the Jews, destroyed a large number of churches in Palestine. Legend has it that the church was spared out of respect for an image on the church façade of the three Magi, who supposedly came from Persia and who were dressed in Persian attire.

The third important stage in the history of the church began during the Crusader period in 1099, when King Baldwin, the second king of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, chose to be crowned in the church on December 25, 1100. The Crusaders added two bell towers, reduced the entrance to only one door, and closed the rest of the main and side gates with stones. Two marble staircases were added to the Grotto of the Nativity, one on the southern side and the other on the northern side.

Prior to 1169 AD, the Crusaders had a series of frescoes painted inside the church. The frescoes expressed religious stories painted with a Latin European flair, obviously in an attempt to influence the heritage of the church. Later, some of the frescoes were replaced with glass mosaics.

A good collection of Crusader frescoes can still be seen in the church and its various chapels although not all are from the Crusader period; some date back to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. However, the most attractive among the paintings are those of the saints depicted on the columns. It is worth mentioning that the artwork left by the Crusaders in the Church of the Nativity could be the most important legacy of Romanesque art and could also be considered among the most important medieval drawings in the world.

Although the history of the drawings on the columns is debatable, that of the wall mosaics is not. There is an inscription in Latin and Greek that dates them. The text mentions the name of the king of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, Amalric (who ruled from 1163 to 1174) and the name of the Byzantine king Manuel I Komnenos (who ruled from 1143 to 1180), as well as the name of Raul, the Latin Bishop of Bethlehem. The inscription indicates that the mosaic was a joint endeavor between the Byzantine Empire and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, a very important and unique example of such cooperation. The text also mentions the name of the artist who created the mosaics, Monk Ephraim. The mosaic works ended in 1169. The emergence of the name Ephraim as well as the name Basil (Syriac) confirms that the artists who worked on this beautiful mosaic were Arab Christians and Syrian Palestinians.

Unfortunately, not all these mosaics survived, but certainly, what remains attests to their exceptional size and location. Normally, the most symbolic and most sacred places in churches (Byzantine churches, for example) are decorated with wall mosaics. Those in the Church of the Nativity, however, are not typical. The mosaic motifs include scenes of the family tree of Christ as described in Matthew 1:1–17 as well as in Luke 3:23–38, which includes many plants, trees, and other architectural forms.

In 1187, Saladin reconquered Bethlehem, but the church did not suffer any damage except for the loss of the bell towers. Saladin restored the presence of the Greek Orthodox, Melkites, and other Oriental sects, in particular, the Armenian Orthodox, as before the Crusaders. Extensive rights were awarded to the Armenians and were expressed through the installation of an exquisitely decorated wooden gate (the Armenian Gate), which links the narthex to the central aisle of the basilica. This gate was made in 1227 AD and decorated with Armenian crosses. The wood-carved gate motifs are fully integrated in Islamic art. Two inscriptions, one in Armenian and the other in Arabic, mention al-Malik al-Mu’zzam ‘Isa (Ayyubid ruler of Palestine) and the King of Sicily, Hethum (who ruled from 1226 to 1270).

During the Mamluk period (1250–1517), most Christian denominations were able to worship jointly within the church, but they no longer had the financial means to carry out the necessary restoration work. Gradually, most of the marble slabs that covered the interior walls were lost.

A good proportion of the wood of the ceiling was replaced in the fifteenth century, which actually proves that the roof of the church was largely restored. The restoration work was completed in 1479, with funding from the Duke of Burgundy and the King of England. But subsequently, the church gradually lost much of its glow and decoration.

The beginning of the Ottoman period was not promising for the Church of the Nativity. The deterioration of its structures continued as it lost more marble. The Crusader door, which is also an abbreviation of the Justinian gates, was narrowed and took on its current size.

Minor restoration work took place, but the physical condition of the church, especially the roof, continued to deteriorate until it became an endangered structure. This world monument with its unique spiritual value, structures, and decorations was at serious risk. This is when the current restoration project was initiated.