Civilizations that write history are often remembered by the cultural heritage they leave for future generations. Therefore, the preservation of audiovisual heritage should be considered a national duty. Yet, collecting and preserving the collective memory has to be done correctly and requires not only a clear vision for the future but also the technical and legal expertise related to archiving. Whoever controls archives and cultural collections decisively influences the writing of history – a principle that has been in evidence since antiquity.

Palestine has always been extremely culturally diverse. Exposed to many foreign influences and subjected to ongoing exploration and study, Palestine fortunately belongs to those places in the world that are well documented. Tens of thousands of pictures were taken around the turn of the century; the first moving picture that was filmed in Jerusalem dates back to 1896; and the first Palestinian commercial music discs were recorded already in the early 1920s. My search for this extremely valuable Palestinian heritage and memory from the very early days of audiovisual documentation revealed that they were to be found outside of Palestine, i.e., not in Palestinian hands! Why?

Five significant phases that are strictly linked to political changes mark the audio-visual history of Palestine: From the beginning of audiovisual documentation until 1948; from 1948 to 1965 – a phase without significant Palestinian audiovisual output (except that produced by UNRWA); from 1965 to 1982 – an extremely productive era in the shadow of the PLO; from 1982 to 1993 – a fairly creative phase, especially in the field of music in the occupied territories; and from 1993 until today – a phase marked by a wide spectrum of productions that reflect various cultural and artistic visions.

Until the 1940s, Palestine was considered a “cultural junction,” a place that offered a high level of intellectuality and cultural diversity, and that attracted explorers, journalists, musicians, and photographers to come and share their expertise. Even the British administration saw in Palestine a fruitful place to establish its first radio station in the region, the Palestine Broadcasting Service, in 1936, and later the second regional radio, the Near East Broadcasting Station, which became the basis for the Arabic section of the BBC. Photo collections and other visual findings of that time have been fairly well researched by such scholars as Issam Nassar and the late Bashar Ibrahim, who was one of the experts on the history of Palestinian cinema, along with George Khleifi and others.

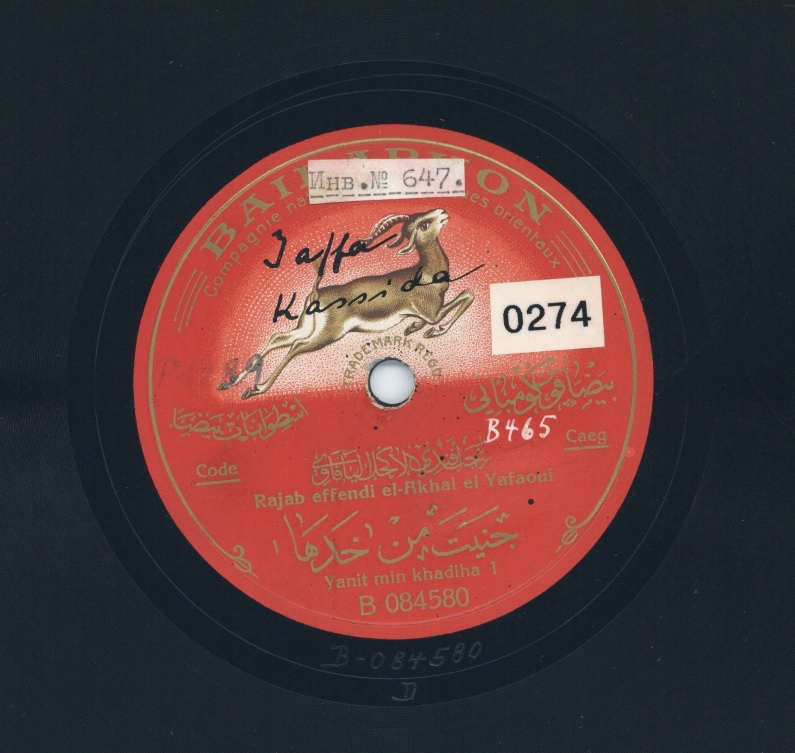

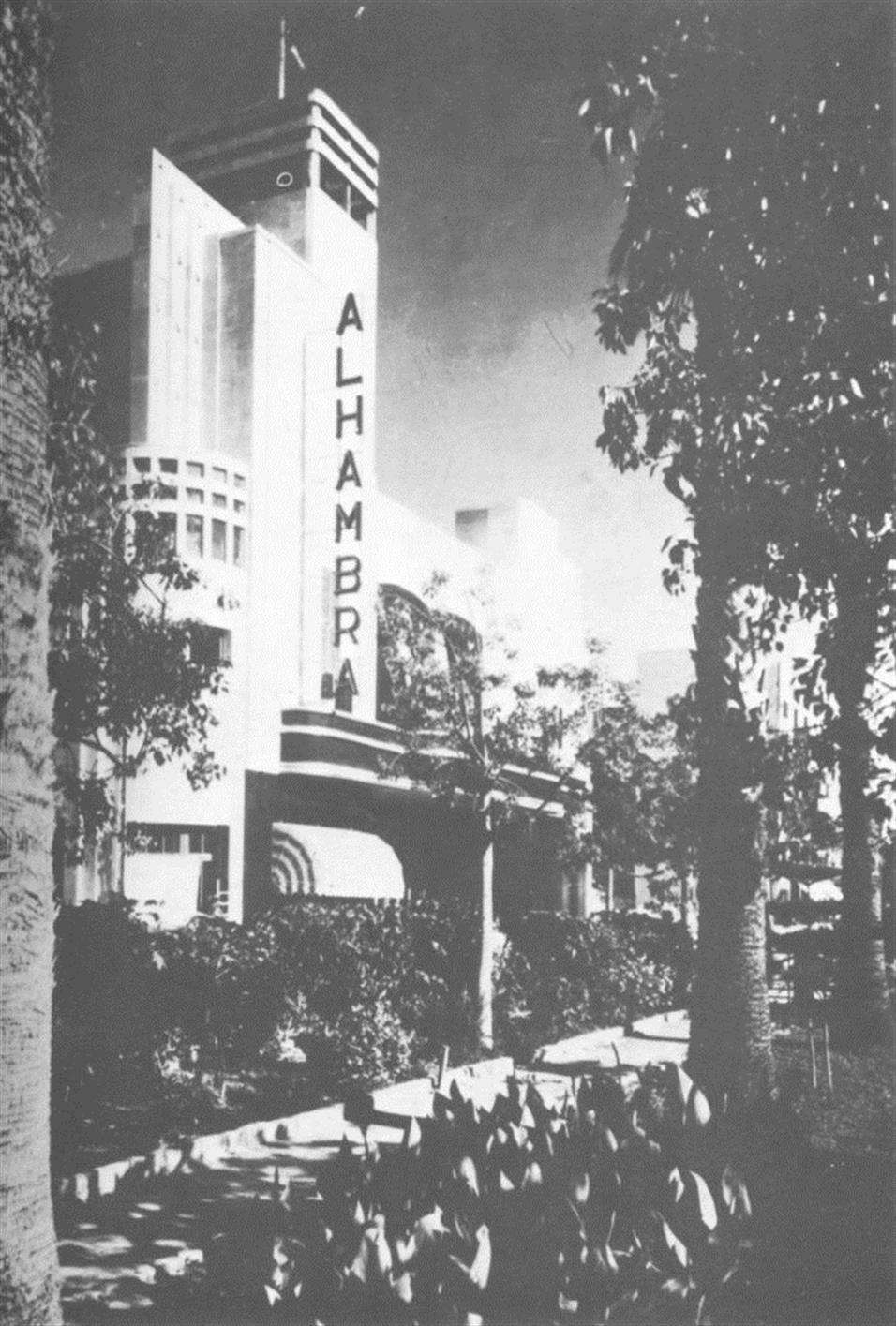

The auditory heritage of recorded sound before 1948, however, has hardly been researched. Other than the efforts of the Ramallah-based “Nawa” (Palestinian Institute for Cultural Development) and some scholars to search for and collect recordings, there is hardly any archived auditory material. Given my sound-engineering background, it was a real joy for me to go through the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv and find two shellac discs by possibly one of the first Palestinian singers to have recorded their music on commercial gramophone records. In the early 1920s, Rajab El-Akhal (from Jaffa), who happened to be the eldest uncle of my mother, Tamam El-Akhal, apparently recorded several shellac discs with Baidaphon, the only Arab-managed music publishing company at that time with its head office in Berlin, Germany. Another two musicians seem to have recorded their music at the same time, also with Baidaphon: Thurayya Qaddoura (from Jerusalem) and Nimer Nasser (like El-Akhal, also from Jaffa). Jaffa appeared to be a lively cultural hub that was also the home of the first Palestinian filmmaker, Ibrahim Hassan Sirhan, and hosted the first cinema (Alhambra) in the entire region, as well as the renowned Near East Broadcasting Station. On the cover of the Baidaphon discs, Jaffa is listed after Egypt and Berlin as the third center for music in the Arab World – even before Beirut and Bagdad, which indicates its importance as a cultural center.

All professionally archived collections of audiovisual materials (mainly photo collections) that refer to Arab Palestine before 1948 are today located in either European, US, or Israeli archives and are partly digitally accessible. There are some smaller collections that still can be found in Palestinian hands here and there, but these are basically private collections, such as various photo collections created by Palestinian and local Armenian photographers. In an attempt to create the first scientifically and publicly accessible Palestinian-controlled visual history archive, the newly created Palestinian Museum has launched a project entitled “Family Album,” which aims to digitally preserve private picture collections that have collective cultural value. Some of these can now be seen online.

During my research in various international archives, Germany turned out to be a real treasure trove. In addition to the above-mentioned two gramophone records from around 1925 that I found in the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, I discovered a huge photo collection in the archive of the University of Greifswald, at the Gustaf Dalman Institute, that consists of around 20,000 pictures of Palestine before World War I. Finding these treasures precipitated a mixture of feelings in me! But in the end, I realized that without Europe’s archive expertise, this part of our heritage would have probably been lost forever!

The big “cut” was the 1948 Nakba; not only because half the Palestinians were forced to leave their homes, but in fact, because all Palestinians have equally lost political self-determination – a fact that wasn’t less dramatic than the expulsion itself. Overnight, the Nakba put an end to this vivid cultural life and to its audiovisual output. Those Palestinians who had once lived together in one unified area found themselves again in four different geopolitical zones: within the borders of the Green Line but as Israeli citizens; in Gaza and the West Bank, beyond the Green Line and under non-Palestinian rule; in neighboring countries as refugees; in the diaspora. This unexpected reality truly threatened to rapidly dissolve the common and collective Palestinian memory.

After 1948, many Palestinian media professionals, especially musicians and radio professionals who had gained their know-how at the British-Palestinian radio stations and who had left their homes, continued their careers in the neighboring countries and thereby influenced the musical life and media landscape of the entire Arab world until the 1990s – including the Arabic-speaking section of the BBC.

Following the Nakba, it took years until the first Palestinian-made audiovisual production saw the light in the mid-1960s, when Fateh established its first photography unit in Amman and the PLO its Cultural Arts Section in Beit Hanina – Jerusalem. Soon after, other media and culture departments were established under the umbrella of the PLO, and it became feasible to produce complex audiovisual works, such as films. Some researchers refer to the first PLO film to be the one by Mustafa Abu Ali from 1968, entitled No to the Peaceful Solution. But I learned from my mother that my late father, Ismail Shammout, who made six films for the PLO, had indeed produced his first PLO-sponsored film in 1966. The film was shot in Gaza and dealt with the first days of the creation of the Palestinian Liberation Army (Jaish At-Tahreer Al-Filistini).

Since its creation, the PLO aimed to employ audiovisual media to communicate with the world and represent the Palestinian cause in a modern and civilized way. Thus, the 1970s and early 1980s became an extremely fruitful period. Thousands of professional pictures were taken, dozens of PLO films were produced, and hundreds of political revolution songs were recorded. Through these means the PLO subconsciously “rescued” a huge part of the musical and also visual heritage, thus reviving our common cultural identity.

The second “cut” came in 1982. This huge amount of audiovisual material created in the shadow of the Palestinian political struggle, mainly in Beirut, was systematically targeted and looted by the Israeli army during the 1982 invasion – and there are several reasons for this systematic robbery! Sadly, no Palestinian really knows the specific content of these extremely important collections that were looted from Beirut. There are no lists and no backups, only fragmented aural testimonies from people who were involved in Beirut. Recently, some copies of the PLO films that were publicly shown at festivals in Europe in the 1970s and 1980s were localized (again mostly in Germany) and digitized; they are now available in the archive of the Palestine Broadcasting Corporation.

According to Israeli historian Dr. Rona Sela, almost all the audiovisual PLO material is kept today in the Israeli Military Archive. Israeli law renders most of it inaccessible, including an enormous amount of non-edited original film footage, photographs, music, and other audio recordings that reflect an extremely important part of the PLO era.

The search for our audiovisual heritage remains a never-ending story, and every day new treasures are created or old ones rediscovered. Yet, in my opinion, what is urgently needed is the establishment of a national institution to professionally manage the preservation of our audiovisual heritage and provide access to the public. This requires not only technical expertise in archiving but also submission to functional legal archiving regulations. All these collections and foreign archives form a vital part of our common Palestinian history.