Saint Nicholas is one of many saints adored in Beit Jala, my hometown. His church, built atop the cave where he lived, has a golden dome that distinguishes Beit Jala from any other town in Palestine. But across the street from St. Nicolas is a place much more captivating: a building that hosts a group of women who years ago decided to create a union to organize their various activities surrounding homemaking and children.

One could easily dismiss this place as just another initiative doing what women have been doing all their lives: cooking and taking care of children. But in the alleyways of this little town, St. Nicholas and its grandiose dome made far less an impact on me as a child than the place across the street, where the work of women filled my nose with aromas of halba (fenugreek), sambusak, and cakes that I can still smell and taste today.

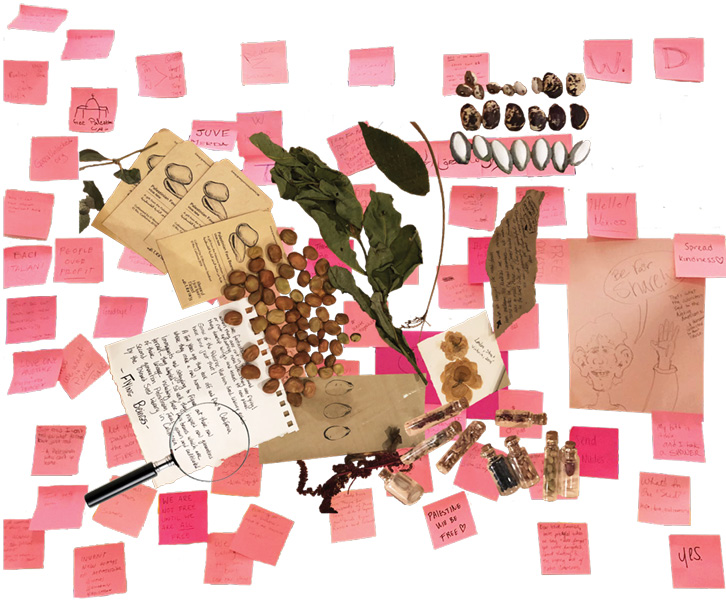

With little interest in church ceremonies, I always found myself sneaking through the back door of the Women’s Child Care Society to sit in the kitchen and watch the women work miracles with their hands. Flour flew like pixie dust across the top of their elongated steel counters as they turned it into dough with which they played, converting it into small triangles of spinach-filled pastries. Spinach, dandelion, and whatever wild greens were in season – they would lay them in small heaps onto the thinly rolled dough and gently wrap them into perfectly matched pockets. How they managed to make them all look identical is still a mystery to me. A grown woman, I have come to appreciate this place more and more as a visionary attempt by women, such as my Aunt Salwa who still runs the place, to claim their own space and find their power in the thing over which they have declared full dominion: the kitchen.

The kitchen was also my mother’s queendom. The only other person allowed to meddle in its pots and pans was her mother, Wadia’. Though it is not nice to make a poor mention of the dead, my grandmother Wadia’ was not the warmest of grandmothers. She was a genius in the kitchen and a master in the garden – a perplexing fact, considering her lack of tenderness as a person. All that aside, I owe it to Wadia’ that I love soil and know a thing or two about raising rabbits; but most of all, that I have mastered the art of making riqaq o addas: a Palestinian country dish that is cooked primarily in the fall, during the olive harvest season.

Riqaq o addas is a noodle-and-bean dish made of two ingredients: flour and lentils. Riqaq denotes a thin dough, and addas means lentils. I would sit and watch Wadia’ instruct my mother on how to stretch her dough and slice it into small strings to make what looks like the Italian version of riqaq, tagliatelle.

But the days of using a knife to make these long strands were over by the time my mother started making them for us. It was a memorable day when my mother purchased a hand-operated apparatus that swallowed the sheets of dough and turned them into symmetric ribbons that descended from the stainless steel machine with each cranking of its handle that was gently operated by my mother.

Even though riqaq o addas was not necessarily my favorite dish, it was for sure one that I looked forward to because I knew that the kitchen would turn into a lab that day. And I would become the observant scientist whom my mother would try to kick out of the way, allowing me to practice more mischief as I attempted to make my way back to the counter where she prepared the meal.

“I don’t want you in the kitchen. Go make a life for yourself!” That was my mama’s mantra. Maybe she wanted to give me a life different from hers, a life in which I would pursue my dreams and make them a reality. She didn’t see the magic in the kitchen. Her life goals had nothing to do with dough or lentils. She wanted to be a nurse, build a hospital, create her own wellness center, and who knows what else. But somehow, she cooked every meal like a master chef and never bought ready-made foods – all the while insisting on leaving me out of the kitchen as a way, I suppose, of saving me from traditions that would suffocate my dreams.

Ironically, it was the kitchen that was always part of my aspirations. It still is. I try out every dish possible from palatal memories, sometimes from instructions that she gives me over the phone while tending her garden in North Carolina. I experience many failures. Some days, I don’t cook the vegetables long enough; on others I cook them for too long. Though sometimes futile, the days when I am able to recreate a taste of my long-gone childhood are worth every failure. Alas, I am not one to shy away from failure. In the kitchen and in life, I cherish it the way I cherish my harsh grandmother for showing me who I want and don’t want to be.

What today is an old-fashioned pasta-making machine for me was once a magical instrument that spat out light-yellow threads that I would sew into a fantastical world that didn’t exist. But who cares? I was a tiny creature trying to dip my fingers into the bowl of wheat and water so I could experience the bouncing dough.

And I want to be a better cook, be it in creating my food or my dreams. The older I get, the more I conclude that there seems to be no distinction between success and failure. Both provide the sweet and the sour – precisely like riqaq o addas that is cooked with wild sumac berries that are tangy and sweet at the same time. We seek them and adore their sour taste with great reverence because we know they are necessary.

“Where is your riqaq-making machine?” I plead with my mother to remember where she might have stored it before she left Beit Jala. Unproductive searches led me to go back to the basic cutting blade and my hands. I mix the flour with the water and add a sprinkle of salt. While I knead the dough, I let the sumac berries soak in hot water, and the lentils get tender as they boil in a different pot. Kneading, I have started to feel, is not for the faint of heart. Perhaps I should join a gym or start weight lifting. My lazy back begins to crack. It seems that our mothers and grandmothers were not only cooks, they were also athletes.

“I won’t give up. I am not going to sit down,” I whisper to myself as I start to see the dough molding itself in my hands. With each twist of my hands, I feel as though I am kneaded into stories of lives that I can only imagine. My mother, grandmother, and grandmothers before them must have used this process to release their burdens into mounds of dough. Maybe they survived not with grief but with smirks in their hearts as their men ate their bread, underestimating the power of knowledge the women had in turning grains into bread.

“The hearts are secrets,” we say in Arabic, so I capitulate to the fact that I may never know if they felt sorrow or power. I must know my own heart’s secret. I am feeling elated as I make my dough.

“Yes. I can.” And so I do. I spread my dough, and I start rolling. As it gets thinner, I am transported into my mother’s body. My hands start to look like hers, and I am suddenly making all the moves and dancing with the tempo of her rolling pin. I am honored to be using the utensil that shaped my mother’s cookies and bread for so long. Scratched and brutalized by years of hard work, the wood looks more alive than it has in years. It is joining me in this return to life. Water, wheat, and salt: the minerals of this earth that once was drowned by the ocean. How do we assert our claims over things that existed before we ever did?

The smell of boiled lentils intensifies as I forget that they were even there. I rush to turn off the stovetop and begin to strain them. Steam fills my nostrils, and I become irritated by my lack of swift attention that has rendered them mushy.

“I bet this never happened to my mother,” I say to myself. “It’s really a simple dish, you see,” she always says, “you don’t need anything to make it. Peel some garlic, sauté it with a bit of olive oil, add the lentils and water, and then add the pasta.” Her instructions always came with a caveat of things she thinks I should somehow know because she forgets how she always kicked me out of her kitchen. “Oh, and of course, don’t forget to strain the sumac and add its juice to the pot.”

I remember every step this time. I finally feel like I am getting it right. My riqaq o addas is going to turn out wonderful. I feel confident as I slice more fresh garlic and place it in a pan full of olive oil. I am making qadha, a signature of many Palestinian dishes. Even bad cooks can fool their audience with qadha: an infusion of olive oil with garlic, using heat to bond them together before adding the mix to the dish in its final stages of preparation.

It doesn’t feel like fall yet. A heatwave that has struck our area is making this dish unfit for this time of year. The sun glares through my kitchen window, and I see its reflection in the golden dome of St. Nicholas. He is still celebrated in my town, in the fall, when he is thanked for being the protector and savior.

Be that as it may, I never felt especially protected by him. It was always the women cooking in the backyard of his church, the master chefs of their homes, and the goddesses like my mother, who sacrificed their dreams so I could have my own, who gave me a feeling of protection.

But that is not who we talk about when we talk about visionaries. We think of people like my mother as “just a homemaker” or “a stay-at-home mom,” as if they were somehow average and not pillars who have shaped our worlds by acts of protection such as feeding us pure food and pure love, represented in their swollen hands, broken backs, and relentless struggles both inside their kitchens and beyond.

How, for so many years, the world reduced the work of mothers around the world to a side job is truly society’s greatest failure. We are still trying to recover from it! And it can only be rectified when we start to understand that the food on our table is not the product of mundane activities but of rigorous physical and mental processes that require discipline, courage, and determination to make our lives a little more tender and a whole lot more tolerable.

But then again, they were just women doing what women always did. And unlike St. Nicholas, they were real and visible, and their power, if acknowledged, was a force to be reckoned with!