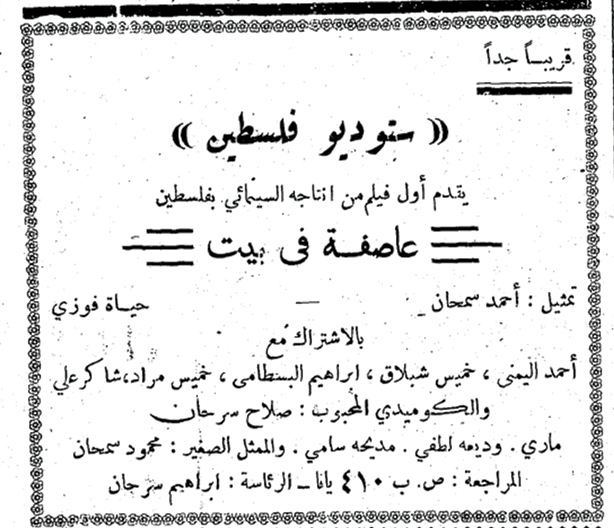

Palestinian cinema, like so many other aspects of our lives, has been and still is heavily affected by the Israeli occupation. History shows that the first Palestinian film was produced in 1935 by Ibrahim Hassan Sirhan, who in 1945 established the Arab Film Company, believed to be the first Palestinian production company. Unfortunately, its life was cut short in 1948, and the films that had been produced are nowhere to be found today. In the two decades following the Nakba, Palestinian film production was timid, if existent at all. It was not until the late sixties, after the Naksa of 1967, that Palestinian cinema emerged again. Over a few years, more than sixty films were produced, most of them Palestinian revolution-related documentaries.

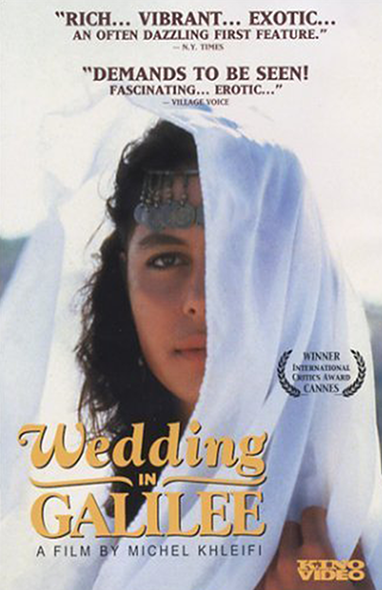

From the late seventies until the First Intifada (1987) the cinema scene in Palestine witnessed the production of more documentaries about resistance and the occupied land. In 1987, Palestinian cinema received international attention when Michel Khleifi’s Wedding in Galilee was awarded the International Critics Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. After a short hiatus during the uprising, the cinema industry in Palestine revived and emerged again after the First Intifada. Several Palestinian films have since received international critical acclaim, among them Chronicle of a Disappearance (1996) by Elia Suleiman.

Cinema plays a powerful role in modern society. It is not only a form of art and a contributor to a nation’s economy but also an important educational tool. Films can influence society’s values and habits, and as tools for cultural guidance and enlightenment they can elevate culture within society’s consciousness. Cinema documents narratives and preserves collective memory. In the Palestinian context, films also have a political function and can be considered as a vital means of resistance, using creative and artistic expression in order to depict the experience of Palestinians both in the diaspora and under occupation.

Today, there is a rising need for locally-produced Palestinian films, as Palestinian cinema is affected by many challenges that stand in the way of it emerging in the regional and international film scene. Most important among these challenges are the lack of a cinematic infrastructure, lack of funding, poor viewership, and the restrictions that are associated with the occupation.

The lack of cinematic infrastructure is among the largest obstacles for the Palestinian filmmaking industry on its way to full blossom – despite the talent shown by local filmmakers. As there are no local film schools, nor film studios, the Palestinian filmmaking industry lacks high-quality filmmaking equipment and crews. As a result, Palestinian filmmakers find themselves faced with two bitter options: outsourcing, by hiring an international crew (with high salaries), or renting equipment from Israel, an option that many filmmakers find unacceptable for ethical and political reasons.

Independent Palestinian filmmakers find it very difficult to fund their projects, partly because there is hardly any formal funding available, as cinema and culture-related projects rank low on the Palestinian Authority’s list of priorities, and as international filmmaking grants come with many restrictions – such as compliance with requests to hire an international crew in return for receiving the grant, acquire a certain percentage of the production cost from local or regional entities (i.e. the Palestinian Ministry of Culture, Palestinian production companies, or Arab Funds. funds; financial support from these entities is rare and difficult to obtain), or allow for interference with the content and changes to the plot to make sure it corresponds to the foreign policy of the country issuing the grant. The prevailing funding difficulties, however, not only prolong the production cycle but also make the building of an infrastructure for filmmakers almost impossible. The scarcity of funds not only affects filmmakers, but filmrelated organizations and events as well. In 2011, Al Qasaba International Film Festival was discontinued due to a lack of funds, and in 2016, Cinema Jenin had to close its doors due to accumulated debt.

The absence of a cinematic culture, poor audience responses, and a lack of demand for independent films is another challenge Palestinian filmmakers are faced with. As a matter of fact, these are challenges for most indie filmmakers. With films that are produced by Hollywood, Bollywood, and other commercial companies occupying our screens, the average viewer has become used to consuming what is being provided and is not searching for content outside his or her small screen.

Last but not least, the occupation exerts a strongly limiting influence on Palestinian cinema. With restrictions on movement and the geographical separation between the West Bank, Jerusalem, Gaza, and the areas occupied in 1948, scouting locations and shooting a film can be a tremendous challenge because many locations are inaccessible for filmmakers with a Palestinian ID.

But regardless of all these challenges, the Palestinian film industry is moving forward. It is able to do so with the suppor t of organizations that are paying close attention to films and to the role they play in the socio-political development of Palestine. Through their various programs, these organizations aim to revive the cinema culture by creating cinematic development, encouraging the cultivation of an extended viewership, and building film capacities. Such programs include, for example, the Women’s Film Festival by Shashat, Days of Cinema by Filmlab:Palestine, Haifa Independent Film Festival, and the Red Carpet Human Rights Film Festival.

Another important program is Ramallah Doc Pitching, which is presented as a collaborative effort between the A.M. Qattan Foundation, the Consulate General of France in Jerusalem, the Goethe-Institut in Ramallah, and Filmlab:Palestine. Ramallah Doc Pitching suppor ts the filmmaking industry in Palestine by providing Palestinian documentary filmmakers with the opportunity to pitch their project ideas to a forum of international film producers and TV representatives; it furthermore assists many Palestinian directors in securing pre-buy deals and post-production grants.

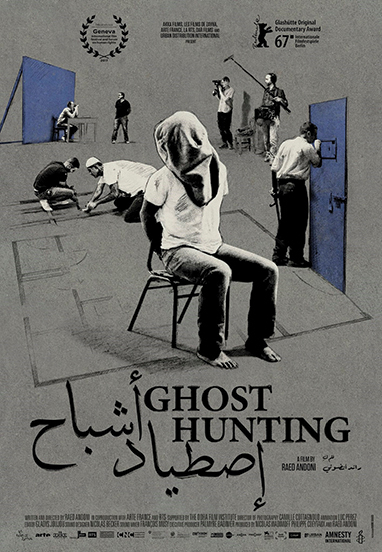

Following the second Intifada (2000), the cinema scene in Palestine has witnessed a number of notable productions. Most of these films depict life under occupation and war and the relationship of Palestinians to their homeland – presented, however, in a more complex and unique aesthetic and with at times controversial plots. Many of these films have succeeded in making their way into international film festivals, such as Raed Andoni’s docudrama film Ghost Hunting, which premiered at the 2017 Berlin International Film Festival and won the main documentary prize. Other notable film productions are Love, Theft, and other Entanglements (2015), a drama by Muayad Alayan; The Wanted 18 (2014), an animated documentary by Amer Shomali; Infiltrators (2012), a documentary by Khaled Jarrar; and Roshima (2015), a documentary by Salim Abu Jabal.

The directors of these films – along with the big names who have left their mark on the Palestinian cinema scene, locally and in the diaspora, such as Michel Khleifi, Elia Suleiman, Hany Abu-Assad, Rashid Masharawi, Annemarie Jacir, Mai Masri, and many others – have overcome the challenges the Palestinian filmmaking industry is facing and have helped in shaping the current cinema scene with their critically-acclaimed productions. It is important to note here that a number of organizations not mentioned above are supporting the film industry in Palestine, yet it is far from enough to fulfill the needs. Palestinian filmmakers have the talent and the unique narrative – they are missing the support of formal and informal local entities.