A Journey into the History of the Palestine Train

More than one hundred years ago, there was a railway in Palestine; about one hundred years ago, Qalandia International Airport was built; and the history of Jaffa Port spans more than three thousand years. Today, Palestine is fragmented, torn, and divided. No civilian aircrafts land here, and its small port in Gaza receives only fishermen’s boats. The railway was dismantled and looted when the trains stopped running on the eve of the Nakba war. Later on, the trains were placed in the Israel Railway Museum in Haifa.

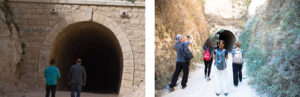

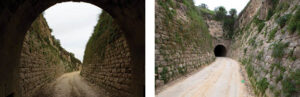

To the east of Tulkarem, the small village of Bal’a hides among olive groves and almonds. On the road leading east to the village of Atara, a strange sight confronts you: an old dirt road with high stone walls adorned with weeds popping up between the stones. It twists a little to the left. Walk a few meters, and you will be surprised to see the dark opening of a narrow tunnel (32.325759°, 35.148817°). I have stood in front of that tunnel trying to hear the train, roaring as it slithers like a snake, blowing thick white smoke, on its journey to Silat al-Dhahr, Arrabeh, Burqin, Jenin, Afula, and Megiddo, all the way to Haifa.

This 220-meter tunnel was part of the Ottoman military railroad that used to connect the northern Sinai with Syria, passing through Beer Sheba and running north through the central valley with lines connecting to Gaza, Jerusalem, Jaffa, Nablus, and Haifa, before the main line veered eastwards, south of Lake Tiberias. It linked with the Hijaz Railway that connected Medina, Saudi Arabia, with Damascus, Syria, via modern-day Jordan. Construction started in 1900, during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II.

In the village of Bal’a, west of al-kharq (the tunnel), as the villagers call it, Abu Raiq, 84, still remembers the roar of the train when it passed nearby: “The train was made of connected farakin (wagons); the first was the motor. It used to pass through here every day, sometimes carrying livestock, sometimes cargo, and sometimes passengers. Sometimes it was long and sometimes short, with three to seven wagons, depending on the load. Its color was a kind of brown, and it was very loud. I’ve never taken the train.”

Nowadays, Palestine is divided into three statelets with limited means of transportation. Lod Airport is inaccessible, Qalandia Airport has been closed forever, and the Palestine Railway Company terminated in the wake of the Nakba when the homeland was occupied, its people were expelled, and a new entity was built on its ruins.

Abu Raiq smiled wistfully when I asked if he wished to see the train making its way across the hills of Bal’a and entering the tunnel again. “There is no time left for me to see this happen,” he said with sorrow. “It’s impossible, or perhaps it would be one of the miracles among the signs of judgment day.” And off he went to the mosque for afternoon prayer.

For more information and guidance on the trail that leads from the tunnel to the Masoudiyeh train station near Sebastia (a 12-kilometer hike on flat terrain), please contact Bassam Almohor at almohor@gmail.com, or through WhatsApp: 00972-52-458-4273 or Facebook @palestinestreetlife.