By Nahla Beier

First of all, it’s not “humuz.” The last syllable sounds exactly like the moss on rocks in your backyard. And the first letter is not a soft “h” but more like a guttural, throat-clearing sound, though softer than the German sound you make when you say “Nacht.” Obviously, you can enjoy hummos mutely; you just might be interested in how it is pronounced by those who have been eating it probably since Ishmael harvested the first beans by Hagar’s well and mashed them up for his toothless mother.

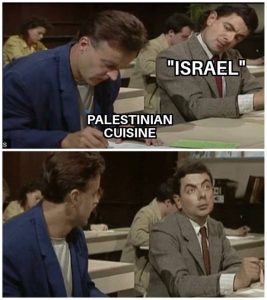

Which brings me to my second point: Hummos is not Israeli, no matter what your favorite celebrity chef or the latest cookbook from Barnes & Nobel proclaims. It is Arabic, hence a food I am qualified to tell tales about. Another thing, we Arabs don’t flavor it with jalapenos or sun-dried tomatoes or basil. We don’t make it out of white beans or pinto beans or black-eyed peas, and we don’t dip carrots or broccoli florets or celery sticks into it. Arabs mash hummos only with tahini, lemon juice, and garlic; we dip into it, or rather, scoop it up with pita bread, and we drizzle only good olive oil on it. We eat it as an appetizer, have it for breakfast with warm kaek (sesame bread), and jazz it up for supper by adding spiced ground lamb and fried pine nuts.

A friend of mine asks me to bring hummos to her numerous gatherings – parties, wakes, and fundraisers. Occasionally, I think of claiming a wider range of culinary achievements, but it is a versatile food that complements happy and sad occasions, it looks festive decorated with olives and parsley, and she really loves it, and I really love her, so I make hummos. So here I am setting the bowl on her sideboard and arranging triangles of pita bread around it when an unfamiliar couple approach, watch me pour golden oil in the moat around the central hummos hill, and dust the sides with paprika.

“Did you make the ‘hamas’ from scratch?” the man asks. I think of pronouncing it correctly for him, but he winks at me, then explains his “nuanced” understanding of my language to his confused partner: “I said ‘hamas’ instead of ‘humus.’ It’s the name of terrible people.”

Now for happier stories. My father often woke up early to buy “the best hummos in Jerusalem” every summer we visited. My mother had died young, so my American husband never tasted her hummos. But Baba swore that Abu Ali’s came close, and by the time we were up and ready for a bite, he had set a table laden with labneh ( yogurt cheese), saber (cactus fruit), za’atar (ground thyme mixed with sesame seeds and spices), pita toasted on the gas range, and in the central place of honor, a plate of soupy hummos mixed with whole chick peas. We argued about the etymology of the word “msabbaha” as oil dribbled down our chins.

“It’s from the root word ‘sabaha’, to swim,” I suggested. “See, the chick peas look like fish swimming in a sea of hummos.”

“I’m sure it comes from ‘masbaha’, worry beads or rosary,” Baba countered. “Notice how the peas resemble a string of beads studding the hummos?”

My husband contently scooped more beaded beige into his pita wedge, venturing no opinion.

So many ways in which hummos weaves itself into the fabric of my life, if a beige, gooey mass can be pictured as somehow weaving. “It’s an excellent source of protein,” I tell guests who have never tried it, “and so cheap to make. A can of chick peas is 92 cents.” “It’s also rich in calcium,” I elaborate, not that they seem to need encouragement. “Palestinian women don’t drink milk, yet they get enough calcium from the tahini to ward off osteoporosis.”

Hummos was a dish I taught my American students to make when they came seeking Arabic culture. We formed teams and creatively decorated the final product with olives and parsley, while music of the oud blared in my kitchen. The winners partook of Arabic coffee and a reading of the coffee grounds with the teacher. “I see a lot of hummos in your future,” I predicted, peering intently into their cups.

My children broke my heart by initially hating hummos. “But my students love it, and your cousins virtually live on it,” I wailed, deeply betrayed. But then their palates developed, or their guilt over neglecting their culinary heritage deepened, and they blossomed into hummos connoisseurs. My youngest told me, grinning, that he had recently taken some that he had labored over to a party, and his host said, “Yeah, Man! You’re the real deal!”

It made my day.