The preservation of cultural identity contributes to a sense of belonging and ownership, especially when it falls within as diverse and multicultural a context as that of East Jerusalem. The Old City of Jerusalem builds upon different eras that have been marked by historical milestones and cultural exchange, which together form a unique identity that cannot be found elsewhere in the world.

The occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) is exceptional in having approximately 7,000 archaeological sites, many of which are internationally known and recognized. Most Palestinian cities, towns and villages have archaeological sites beneath or close to their historic centers that reflect their cultural identity and continuity. Some of these sites have helped change historical assumptions, perceptions, and theories, and added new aspects to international cultural history, such as the UNESCO inscriptions of “Palestine: Land of Olives and Vines – Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir” and “Birthplace of Jesus: Church of the Nativity and Pilgrimage Route, Bethlehem.”

When in 1981, Jordan nominated Jerusalem (“Old City of Jerusalem and its Walls”) as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it was the explicit, agreed-upon understanding that inscription should in no way be regarded by any state as a means of registering political or sovereignty claims. The World Heritage Committee’s inscription of Jerusalem on the List of World Heritage in Danger constituted their acknowledgment of the existence of genuine danger to Jerusalem’s religious properties and architectural heritage. Threats of destruction in the Old City are on the one hand due to uncontrolled urban development and on the other hand exacerbated by a general deterioration in efforts towards conserving the city’s monuments. Such neglect is apparent in the prevailing lack of maintenance interventions, which persists despite disastrous impacts that are caused by tourism.

The safeguarding of the monumental religious and cultural heritage of the Holy City of Jerusalem has been among UNESCO’s main concerns since 1967, and particularly since the site was inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger in 1982. Unfortunately, the architectural heritage of the Christian, Armenian, and Muslim quarters of the Old City is facing alarming deterioration, destruction, and negligence due to a lack of resources and the current geopolitical situation.

Over the past ten years, UNDP has worked actively in supporting the culture and tourism sectors in the oPt through the restoration and rehabilitation of cultural heritage sites and the upgrading of touristic facilities and networks. In a number of donor-funded programmes, UNDP has restored and preserved several historic sites in the old cities of Bethlehem and Hebron as well as seven historic and archaeological sites in the northern West Bank; UNDP has furthermore upgraded Ein es-Sultan spring in Jericho, restored Al-Basha Palace in Gaza, and constructed the Cultural Palace in Ramallah, among other projects – all part of ongoing efforts to develop the cultural infrastructure of the oPt. Moreover, UNDP is currently implementing a housing-rehabilitation project in Jerusalem’s Old City, with the aim of improving the physical living conditions of its residents.

As part of UNDP’s ongoing partnership with the European Union, a safeguarding project is currently being implemented near Souq Al-Qattaneen (Cotton Market), which leads to one of the gates of the Haram Al-Sharif (Al-Aqsa Mosque Compound). This intervention covers the restoration of cultural heritage sites in the Old City of Jerusalem through the rehabilitation of two historic compounds, namely Al-Madrasa Al-Kilaniyya, as well as Hammam Al-‘Ayn and Hammam AlShifa.

Al-Madrasa Al-Kilaniyya – owned by the Islamic Waqf and situated in the central section of the Muslim Quarter near Bab Silsila, one of the main entrances to the Haram Al-Sharif – is a very fine example of Mamluk religious architecture. The typology of the madrasa (school) is enriched by the presence of a turba (Islamic funerary building), and its main facade is among of the most distinguished in the neighborhood. The building’s architectural integrity is seriously threatened due to structural additions and damages to its precious stonework that reflect an overall state of widespread decay, caused by its present usage as an overcrowded housing complex. This rehabilitation also responds to pressing social needs by improving housing conditions for resident families (the building holds ten housing units) and carries a multiplier effect on the Bab Silsila residential neighbourhood: it provides an opportunity to raise awareness of and develop par ticipation and ownership within the neighborhood community, in particular with regards to the conservation of historic sites.

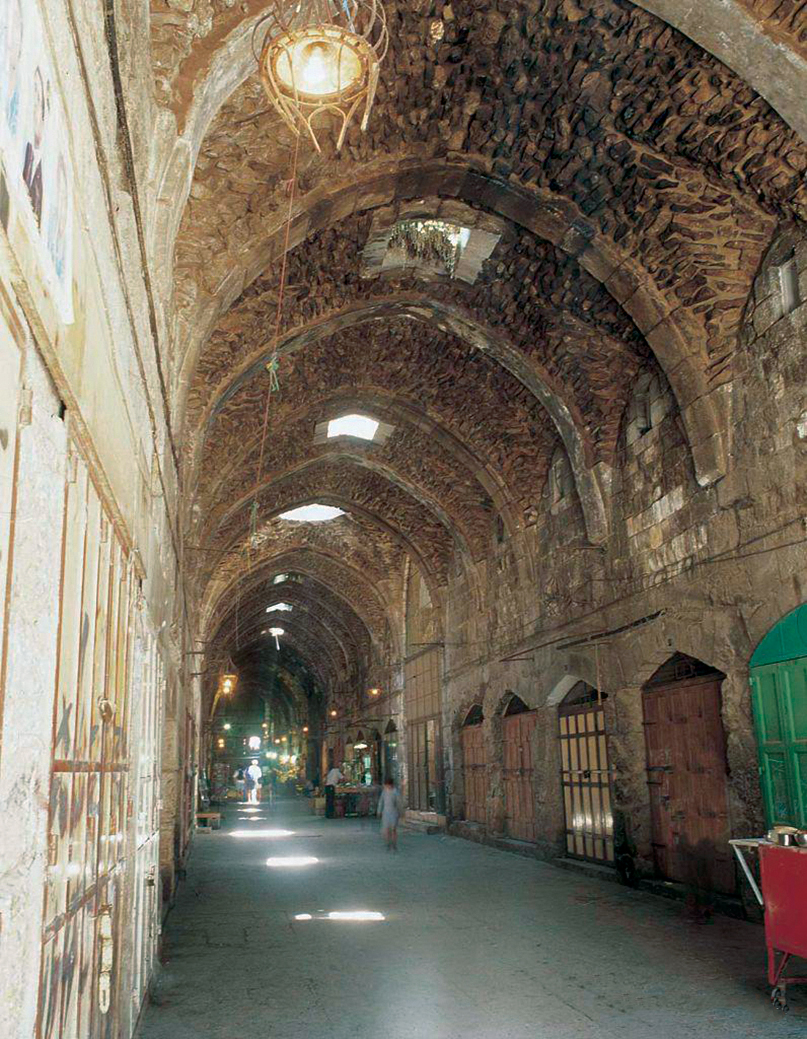

Hammam Al-‘Ayn and Hammam AlShifa are also owned by the Islamic Waqf, but rented to Al Quds University. They are located in Souq Al-Qattaneen, a large commercial center that comprises a long, covered market street with shops on either side, monumental entrances at each end (one of them leading to the Haram Al-Sharif), living quarters above the shops, two public bath houses known as Hammam Al-Shifa (the Bath of Healing) and Hammam Al-‘Ayn (the Bath of Spring), and a khan or caravanserai (traditional resting place for travellers).

The plans of such bath-houses showed little variation in the Mamluk period and were derived from Roman baths. From a changing room, bathers progress through cold and warm rooms to the hot room. The bathing rooms are roofed by domes perforated with little circular windows through which shafts of light penetrate the steamy atmosphere. Latrines are generally isolated from the changing room by a long passageway.

The architectural integrity of these buildings is seriously threatened and exhibits an overall condition of disintegration and decay that is due to their disuse. The rehabilitation of these baths also contributes to the preservation of identity of urban culture for the area and its residents and visitors alike, since hammamat (plural for hammam, bath) are integral in the collective memory of the Arab Islamic world, and specifically in the Old City of Jerusalem. While one hammam will be restored in order to be used as a cultural center or museum for Al-Quds University, the other will be brought back to life and made to work again within its historical and social context: it shall provide people, especially young people, with the opportunity to use the hammam and take baths and steam baths. Thus, this intervention shall also reconnect the building with its unique social function as a gathering place in the neighborhood.