The seeds of Palestinian Liberation Theology (PLT) go back to the days of the Nakba, 71 years ago. About 750,000 Palestinians were driven out or fled in fright from their homeland in the face of the brutal onslaught of the Zionist underground militias. These militias were carrying out a premeditated plan to rid the country of its Palestinian Arab citizens.

When I look back today, I can discern a three-fold Nakba. It was a human Nakba of enormous magnitude. It was an identity Nakba that made us strangers in our own land, and it was a theological Nakba that pulled the ground out from under our feet and added to our feeling of being utterly lost. Our lives were like a ship whose anchor had broken loose and was drifting aimlessly. For the next 18 years, we, the Palestinians living in the newly formed Israeli state, were placed under very strict military rule that controlled every aspect of our lives.

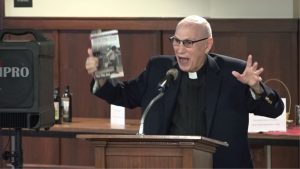

When eventually the curfews were eased and we were able once more to go to church, everything was the same – the liturgy, the Bible readings, the sermon, and the hymns; whereas outside, our lives had been turned upside down. In his book, Justice and Only Justice, a Palestinian Theology of Liberation, Rev. Naim Ateek, the father of PLT, who himself, together with his family, had become an internal refugee in Nazareth, describes what happened.

“The establishment of the State of Israel was a seismic tremor of enormous magnitude that has shaken the very foundations of their beliefs…The fundamental question of many Christians, whether uttered or not is: ‘How can the Old Testament be the Word of God in light of the Palestinian Christian’s experience with its use to support Zionism?’” (pp. 77–78)

It is said that theology is a bridge that leads humans to God. For Palestinian Christians, this bridge had collapsed, and we were caught in the crack, unable to go back to our former theological thinking while groping to find a meaningful way into the future. Whether it was Western feelings of guilt or the theology of Christian literalists, or the ideology of Jewish Zionism, the Bible was used to legitimize the tragic fate of the Palestinian people.

Israel was not established without the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages, the creation of some 750,000 refugees, and the destruction of the national and political life of the Palestinian people. Our faith seemed to clash with the reality of our lives.

My generation grew up under the influence of Western-dominated theology, especially during the British Mandate period when many schools were run by British missionaries. Scripture was taught through their lenses and, whether consciously or unconsciously, it was done in a way that supported the policy of the British government towards facilitating the establishment of the “Jewish homeland” in Palestine.

At the beginning of Naim Ateek’s ministry in the Anglican Church, he was determined to find answers to the many theological questions that alienated people from their faith at a time when they most needed consolation, hope, encouragement, and direction in their lives. He took time off to read the Bible with Palestinian eyes and reflect theologically on the tragic experience of the Palestinian people through the eyes of faith. Our faith crises intensified after the 1967 Six-Day War when the rest of historical Palestine – the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip – fell under Israeli occupation. Religious Zionism flourished, and it was evident that they would hold onto the land “that God had given them.”

Naim Ateek formed a committee of concerned Christians from the various local churches, who after a series of workshops organized an international conference in order to put this Palestinian reading of the Bible in the context of liberation theologies around the world.

After the conference, the founding members decided to start a ministry among Palestinian Christians to help them come to terms with their faith in the light of their experience, and to draw on their faith to work for justice, peace, and reconciliation.

Bible study was the mainstay of this new ecumenical ministry. We tried to discern what God was saying to us here and now, and to “develop a spirituality based on justice, peace, nonviolence, liberation, and reconciliation for the different national and faith communities” (Purpose Statement of Sabeel).

Right from the beginning, PLT stressed that there could be no liberation for one side with the enslavement of the other, and that the well-being of one side would be bound to the well-being of the other side. A way had to be found for sharing the land in order to turn the present curse into a blessing for all.

Some theological anchors of Palestinian Liberation Theology

One of the most stimulating ideas that affected the Palestinian Christians was the discovery that Jesus himself was a Palestinian who lived and died under the Roman occupation. Such a discovery connected Palestinian Christians with their first-century ancestors. It made Jesus accessible to them in his humanity and his relationship to the land, the people, and the powers. Jesus was a tangible person, and his ideas and teachings began to unfold in greater clarity for Palestinian Christians. Such relevance produced two important outcomes.

First, Jesus began to be seen as a paradigm of faith. Christians could look to him and model their lives after him. Jesus experienced the harshness of life under an oppressive occupation similar to the way our people were and still are experiencing oppression.

Second, Jesus Christ became a criterion for measuring, judging, testing, and evaluating people’s actions today. Jesus Christ inspired us to action; and like him, many of our people were ready to use his nonviolent methods. Jesus became the hermeneutic for interpreting the Bible, especially problematic texts in the Old Testament

A further anchor was the priority of justice and the recognition that a lasting peace can only be built on justice. Justice is the business of the church, and the church has to take a stance on truth and justice. The time is ripe for the government of Israel to admit the wrongs and injustices it has committed against the Palestinians and to accept sharing the land of Palestine with them. The Palestinians, with their diversity of religious backgrounds, are the true indigenous people of the land.

Looking back at the journey of the last 30 years, it is true to say that whenever we proclaim the Gospel, we are in essence proclaiming liberation. In a sense, we see liberation as the essence of our Christian faith. Liberation is a comprehensive word. In both the original Hebrew and Greek, the meaning includes salvation, deliverance, and rescue, as well as well-being and healing. In fact, the concept of a theology of liberation emerged from a context of oppression and injustice. Wherever oppression, domination, and injustice are found, it is natural for human beings to seek freedom and liberation. From this perspective, Jesus Christ is our liberator.

In the context of Palestine and Israel, liberation theology developed formally more than 40 years after the Nakba; yet its roots were probably unconsciously hidden in an earlier time as it was ripening and maturing in the Palestinian soul and mind. We are sure that some clergy as well as laity were practicing some form of liberation theology without naming it. Indeed, all along many people were engaged in the resistance struggle. Many chose armed struggle; others chose peaceful and nonviolent means. Many were imprisoned and deported, while some lost their lives. It is possible to say that the flame of truth and justice has never been extinguished. People were aware of the military might of Israel as well as the ability of its security forces to apprehend any suspect and neutralize those who were perceived as a threat. In spite of this, people resisted by various nonviolent methods.

At the same time, due to the conflict over Palestine, the faith of many people was shaken. For those who continued to cling to faith, their theology reflected a sense of despair and resignation. It was a passive waiting on God. PLT, therefore, was the spark that ignited the fire that started doing two things. First, it burned the chains of the oppressive theology that shackled many of us; and secondly, PLT was the light that guided us on our way to fathom a deeper understanding of God in Christ and to discover the wonderful message of the Bible about a loving God who loves all people equally and wills justice, peace, and liberation for all.

Finally, from the very beginning, PLT was committed to nonviolence and emphasized three essential gradational points: justice, peace, and reconciliation. Justice must be done first. It is justice that can produce peace, and peace is what can open the door for reconciliation.