Palestine occupies a central location in the southern part of the Levant between Eurasia and Africa, a narrow stretch of fertile land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and is part of the Middle East and the Arab world. The modern State of Palestine lies within the 1967 borders, with East Jerusalem as its nominated capital.

Despite its small size, Palestine has extraordinary geological features, namely, its coast, mountains, desert, the Jordan Valley, and the Dead Sea, which is the lowest point on earth. Its diverse topography has led some to call it “the small continent.”

Palestine, Filastin, is known in historical sources by various names: the land of Canaan, the land of Retnou, and the commonly used Holy Land. It is also known as the land of prophets; the home of the three monotheistic religions, Islam, Christianity, and Judaism; the birthplace of Jesus Christ; and the place of Prophet Mohammad’s heavenly journey to Jerusalem.

The name Palestine is derived from the ancient name Philistines, identified with Peleset, one of the ancient sea-people confederations mentioned in the Egyptian sources in the Medinet Habu temple, dating to the eighth year of the reign of Rameses III, around 1185 BC. The Philistines were depicted on the temple of Ramses III and were portrayed as warriors and prisoners with their chariots, ships, and distinctive headdress in the naval and land battles against the sea people.

The land of Philistia was mentioned in the Bible as a geographic name, including the Pentapolis, the five Philistine cities (Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath). The Philistines appear in the Assyrian historical sources of the ninth century BC. Palestine was mentioned in the early Greek sources both as a geographic name, Palaistinae, and as a people, Palaistinoi, and as a geographic name in the histories of Herodotus from the mid-fifth century BC. The Hellenistic sources from the third century BC mentioned Palaistin. The term was used to describe the entire area between Phoenicia and Egypt.

The current Arabic name Filastin (فلسطين) is derived from the ancient name and appears on coins and in ancient historical texts of this period, still preserved as the current Arabic name Filastin.

Throughout the millennia, Palestine has been a meeting place for successive civilizations and a cultural bridge between East and West. It has played an important role in human history as evidenced in its rich and diverse archaeological, historical, and religious heritage.

Palestine contains thousands of archaeological sites and historical buildings that are distributed throughout the entire country and range in date from the Stone Age to modern times, reflecting the wealth and cultural diversity of the land.

Systematic archaeological excavations in Palestine began at the end of the nineteenth century, yielding vast quantities of archaeological objects. Archaeological research and excavations that were carried out in more than 1,000 archaeological sites during the last century have revealed much information about past social and economic systems in Palestine – the way people lived, cultivated the land, built their homes, exchanged their products, and managed their resources.

The prehistoric period in Palestine is divided generally to three main periods, Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic. The Paleolithic period dates to more than one million years ago and is associated with hunting and food gathering; it is represented by the prehistoric caves of Um Qatafa and Irq el-Ahmar in Wadi Kharitoun, east of Bethlehem. In the cave of Um Qatafa, the first evidence of human use of fire in the Near East was found. The material culture of this period consists mainly of flint tools.

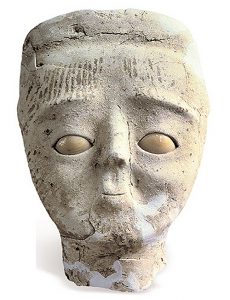

The Neolithic period in Palestine, represented at Tell es-Sultan in Jericho, marks the transformation in human history from a prehistoric subsistence pattern based on hunting and gathering, to a new subsistence pattern based on domestication of plants and animals. The farmers in the early Neolithic settlements built houses and invented pottery.

Evidence of the transitional Chalcolithic period has been surveyed and attested in a wide range of archaeological sites in Palestine. The material culture of this period indicates an economy based primarily on agriculture and animal husbandry. This period witnessed the second revolution, indicated by the use of secondary animal products and the copper industry for the first time in human history.

The Early Bronze Age marks the emergence of the first urban culture in Palestine. This is characterized by the establishment of large urban centers that were based on agriculture and trade metallurgy, religion, the invention of the alphabet, writing, and literature. These urban centers, described as the Canaanite city-states, are represented in Jericho, Tell el-Ajjul, Tell es-Sakan, Tell et-Tell, Jerusalem, Tell Dothan, Tell Taannek, etc.

The Iron Age witnessed the appearance of the ancient Hebrews and Philistines. The Philistines appear in the biblical narratives as inhabitants of the southern and coastal areas, with their king Abimelech and in the duel between David and Goliath in the course of struggle between the Philistines and the Israelites. It is also accepted that the Philistines were the first to introduce iron to Palestine. In 722 BC, the northern part of Palestine was under Assyrian rule. In 539 AD, Palestine fell under Persian rule.

In 330 BC, Alexander the Great conquered Palestine. The Hellenistic rule during the Seleucid and Ptolemaic periods lasted for three centuries. During this period Palestine was a place of cultural interaction between Orient and Occident. It witnessed the rise of urban planning as evidenced in the Hellenized cities in Palestine.

The Roman period in Palestine dates from the conquest of Pompey in 63 BC to the adoption of Christianity as the imperial religion in 330 AD. This period witnessed great cultural changes with the establishment of the new cities of Aelia Capitolina, Neapolis, and Sebastiya, and the introduction of a network of road systems marked with milestones, in addition to major water projects, represented by the Jerusalem water aqueduct and Solomon’s pools from the first century AD.

During the Roman and Byzantine periods Palestine was divided administratively into three districts, known as Palestina Prima (first), Palestina secunda (second), and Palestina tretia (third). Palestine flourished during the Byzantine period, as evidenced by the large numbers of settlements, churches, and monasteries. Palestine was depicted on the Madaba map in the sixth century AD, showing the main Palestinian cities of Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Jericho, Nablus, and Gaza. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem are a living testimony to this period.

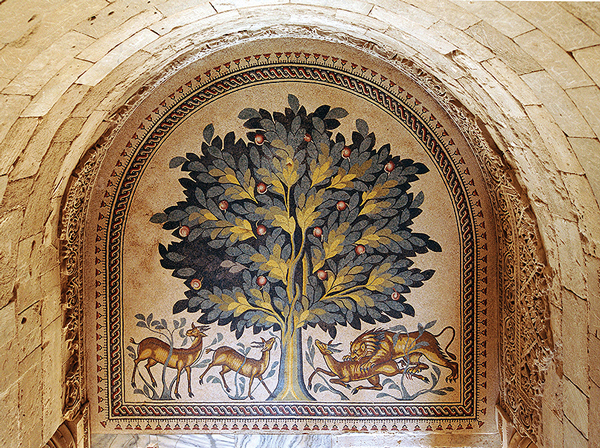

Palestine fell under Islamic rule in 636 AD after the Battle of Yarmouk. The Umayyads were the first Muslim dynasty to rule Filastin after the Rashidun Caliphate. It was renamed Jund Filastin, following the Roman administrative division of Palestine. Ramla was established as a political capital of the province and Jerusalem as the spiritual capital. Historical and archaeological sources have shown how life thrived during the early Islamic period, as evidenced in the huge construction program in Jerusalem, especially the Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock. The Dome of the Rock was built by Caliph Abdel-Malik ibn Marwan in 691, and the Aqsa Mosque by Al Walid I, 705–715 AD. Moreover, this period witnessed the foundation of new cities such as Ramla and the construction of monuments and palaces such as Hisham’s palace at Khirbet el-Mafjar in the Jordan Valley.

Palestine came under Abbasid rule between 750 and 969 AD. The Abbasids continued the policy of their predecessors in Jerusalem and fortified the coastal area. Following a short presence of the Fatimids in Palestine between 969 and 1099 AD, the country was under Crusader rule for almost two centuries, with the establishment of the Latin Kingdom and Jerusalem as its capital. The Crusader presence began to retreat after the Battle of Hattin in 1181, led by General Saladin, and in 1292 the last fort in Acre met its end through the Mamluks, who ruled Palestine until 1516. During this time, Palestine witnessed a period of prosperity as evidenced by tremendous architectural development, especially in Jerusalem and other urban centers.

In 1516, Palestine became a province of the Ottoman Empire. Construction flourished in Palestinian cities, as evidenced in the rebuilding of the wall of Jerusalem by Suleiman the Magnificent. Palestine produced olive oil, cereal, cotton, and glass. Local and regional trade routes were served with khans and castles. The water supply to Jerusalem was improved by the renovation of Qanat es-Sabil and Solomon’s pools south of Bethlehem.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, some local powers rose in various parts of the country and established autonomous political powers under the Ottoman rule. This period was interrupted in 1831 with the nine-year Egyptian occupation by Muhammad Ali, and Ottoman rule was re-established again until World War I, when Palestine fell under the British Mandate, which lasted till 1948.

The population of Palestine at the end of the Ottoman period was predominantly Arab (more than 94 percent). The Zionist colonial project in Palestine was implemented under the British Mandate, following the Balfour Declaration in 1917. Palestinians revolted against British and Zionist policy in 1930 and 1940. In 1947, the United Nations adopted a resolution for the partition of Palestine into two states: one for Arabs and one for Jews, with Jerusalem to be put under a special international regime. Israel was established as a settler-nation project in 1948 and immediately took over approximately 26 percent of the territories of the Arab state. In 1967, it occupied the rest of the land in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip.

The modern history of Palestine is marked by great political upheavals, the most significant of which was the Nakba in 1948, the exile and the struggle for independence. More than 900,000 Palestinians were driven from their homes. After six decades of this great tragedy, Palestine is still the homeland and a living memory for millions of displaced Palestinian refugees who live in the shatatt (diaspora).

The Palestinian resistance moved through several stages, from Palestinian revolts against the British colonial power to the establishment of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), to the Intifada, the declaration of independence of Palestine in 1988, the (interim agreement) Oslo Accords, and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority on part of the Palestine territories. This situation enabled Palestinians to start a process of state building, based on principles of democracy, freedom, and tolerance. In 2012 the United Nations General Assembly acknowledged Palestine as a non-member state and as a full member in international organizations.

Palestine is distinguished by its rich and diverse cultural and natural heritage, the abundance of its archaeological sites, its unique and sacred landscape, and the historic cities of Jerusalem, Gaza, Hebron, Bethlehem, Ramallah, Al-Bireh, Jericho, Nablus, Jenin, Tulkarem, and Qalqilya.

Palestine’s unique geopolitical position, its multi-layered history, and its identity as a cultural mosaic place it at the core of human history.

» Dr. Hamdan Taha is an independent researcher and former deputy minister of the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. He served as the director general of the Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage from 1995 to 2013. He is the author of a series of books as well as many field reports and scholarly articles.