The planning and building crisis in Area C dates back to the early 1970s, when shortly after the 1967 war, the Israeli authorities abolished all Local Planning Committees, essentially the Palestinian village councils, along with all District Planning Committees. As a consequence, Palestinian representation was eliminated from the hierarchy of the planning regime and all planning decisions were concentrated in the hands of the Israeli Higher Planning Council (HCP). After the signing of the Oslo Accords, the Palestinian authority received the right to plan in only forty percent of the West Bank (Areas A and B), while planning in the remaining sixty percent, known as Area C, was under the mandate of the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA). The latter, concerned with the geographical containment of Palestinian localities in Area C, adopted outdated plans from the British Mandate era and special plans prepared by the Israeli military during the 1980s that delineated the village boundaries as the basis for their decision making. These so-called blue lines were drawn tightly around the existing built-up areas in a process that never consulted the local communities. The ICA and felt justified to consider new buildings outside the blue lines as illegal structures and since 1993, very limited numbers of permits were issued for new buildings outside these borders, while demolition orders were generously delivered and executed in Palestinian communities in Area C.

In 2011, in a step aimed at opposing and stopping the Israeli policy of unjustifiable demolition and forced displacement of the Palestinian population in Area C, the Palestinian Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), supported by the Palestinian cabinet, adopted an alternative planning approach. Based on the prevailing Jordanian Law number (79) – which states that each local council has the right to initiate planning in its village and which is binding for both Palestinians and Israelis in the occupied West Bank – the MoLG was able to argue that plans initiated by the local councils and prepared with the local communities should be reviewed by the ICA to grant them approval and authorization as statutory documents, thus considering new expansion areas as legal zones for building and development.

♦ For almost two decades, basically since its creation, Area C has been excluded from any statuary planning initiative of the Government of Palestine (GoP) in the West Bank whose planning was concentrated in Areas A and B. In 2011, in order to circumvent the occupation authority’s policies of forced eviction and demolition that were based on the pretext that the land in Area C was uninhabited, the Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), supported by the Palestinian Cabinet, started to follow an alternative planning approach by drafting local outline plans and implementing them under certain conditions without necessarily securing direct and overt official Israeli approval. This process was undertaken together with the local communities to make sure that their needs and aspirations are properly addressed.

Since 2011, the MoLG has commissioned private Palestinian planning firms to draft 108 spatial outline plans targeting around 100,000 persons and covering the 116 most affected localities in the West Bank, irrespective of whether they are close to the Green Line, settlements, the Apartheid Separation Wall, or even inside restricted military zones. The plans are funded by six different channels: by the Palestinian government, Belgium, France, and the UK, while the EU funded the detailing of a number of the already prepared plans. Seventy-seven of the local outline plans were submitted to the ICA. However, as the discussion phase requires an unreasonable amount of time due to the requirement of obtaining the approval of all subcommittees in the ICA, approximately half of the submitted plans are stuck in the technical discussion phase. Only three plans have succeeded in receiving a positive final authorization when – after three years of discussion sessions moving back and forth – plans for the villages Imneizil in the Hebron district, Tas Tirah and Al-Dabah mear Qalqilya, and Wadi Al-Neis near Bethlehem received approval. Another five plans have been announced for public objection for more than a year now – six times longer than the conventional time span; seven plans have been rejected, as it is claimed that these communities are illegal and do not exist as individual villages.

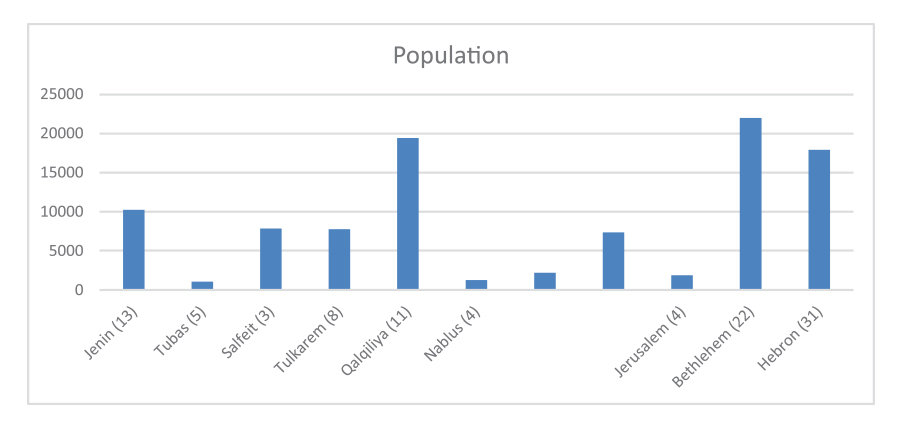

Impact of planning initiatives across the West Bank (2015):

Table 1: The Popuation per Governorate that Benefitted from

Development Plans

With the number of plans in each governorate indicated between brackets. (Source: Ministry of Local Government, 2015)

Despite the fact that only three plans were approved, the MoLG considers this initiative a breakthrough: it has built the capacity of over one hundred Local Government Units (LGUs) across the West Bank and has increased their awareness of their rights to the land and to adequate service provision. It also illustrates a remarkable success in terms of emphasizing the importance of participatory planning, as all plans were prepared directly with the local communities. Whether authorized or not, the plans are fully adopted by the local communities as the tangible result of their efforts in conceptualizing their development needs and aspirations and in then reflecting them in form of local outline plans. Currently, 108 local outline plans have been endorsed by the local councils and the MoLG; they are used not only as a basis for fund raising, but also for the implementation of development and infrastructure projects for plans which have been submitted to the ICA for a period of more than eighteen months (which currently is the case with sixty-one plans). The latter practice has been implemented since late 2014, following an agreement between the MoLG and the European Union, when several projects were nominated to receive funds before their local outline plans had been formally approved.

Thus, several villages have been successful in creating facts on the ground according to the plans, either by constructing an individual building, such as a school or kindergarten, or by establishing water networks. “The outline plan of Um Arrihan was a tool to implement several infrastructure projects, most importantly electricity,” said the Mayor of Um Arrihan. “The initial plan prepared by the ICA was only for 56 dunums (5.6 hectares), but after two years of training and capacity building with MoLG, I was equipped with the knowledge to make a legal argument against the Israeli planning proposal. After three sets of negotiations with the ICA, where we presented our alternative plan drafted by the International Peace and Cooperation Center (IPCC), we achieved a plan covering 122 dunums (12.2 hectares) that reflects the needs of the community for the next fifteen years; and we no longer receive demolition orders inside the planned area.”

For almost two decades, basically since its creation, Area C has been excluded from any statuary planning initiative of the Government of Palestine (GoP) in the West Bank whose planning was concentrated in Areas A and B. In 2011, in order to circumvent the occupation authority’s policies of forced eviction and demolition that were based on the pretext that the land in Area C was uninhabited, the Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), supported by the Palestinian Cabinet, started to follow an alternative planning approach by drafting local outline plans and implementing them under certain conditions without necessarily securing direct and overt official Israeli approval. This process was undertaken together with the local communities to make sure that their needs and aspirations are properly addressed.

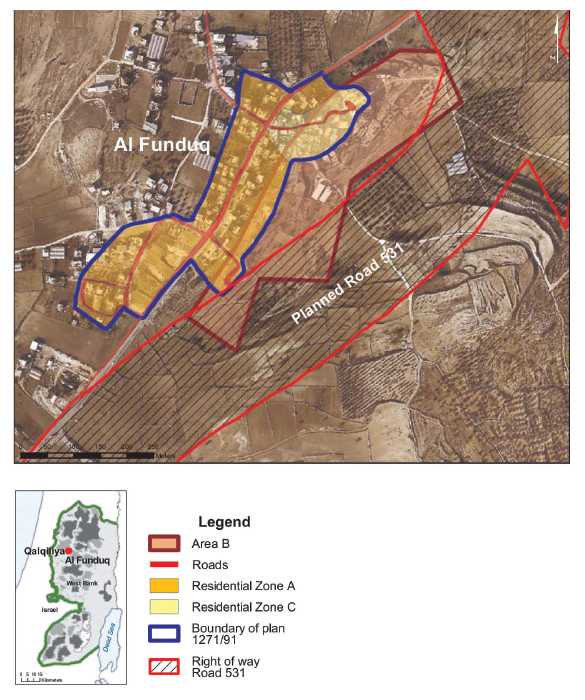

The special outline plan for the village of Al-Funduq and the route of Road 531, which has not been constructed

In summary, this planning initiative was a step towards achieving development goals, reclaiming the right to the land, and asserting Palestinian sovereignty. As any pilot initiative, it had its successes and failures. On the one hand, it has empowered the local communities, incited them to be proactive, and illustrated that people should be the core of any planning intervention. On the other hand, the authorization process requires an unreasonable effort in time and procedures and the localities whose plans were rejected are still suffering from the threat of demolition and other risks that include stop work orders, the confiscation of equipment, or forcible displacement by the ICA for those living inside restricted military zones. It is also critically important to deal with these plans as temporary solutions, as temporary documents that need to be updated regularly in order to accommodate the emerging needs of the communities. Finally, in each governorate, these plans should be linked to the national vision and to regional development trends in order to achieve cohesive planning in all Palestinian land, regardless of the geopolitical divisions.

» Wafa Butmeh is an Urban Planner in UN-Habitat based in the Ministry of Local Government. She graduated from Birzeit University in 2013 as an architect with emphasis on urban planning.

» Jihad Rabayaa, Head of Geographic Information System (GIS) at the Municipality of Ramallah and of the Surveying Department\Ministry of Local Government, has been working with the MoLG since 1995.