“Sometimes I longed to be able to write a novel and make Jerusalem its locale. I wished I could capture the mood and the spirit of Jerusalem, describe its houses and streets and the lives of its people.”

Thursday, June 26, 1947, HalaSakakini

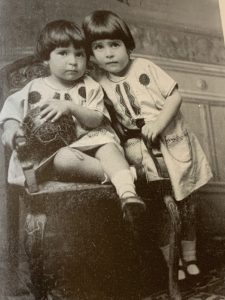

Qatamon is a southwestern, predominantly Greek Orthodox suburb of Jerusalem, west of the train station and up the street from the German colony. It is squeezed between the ostentatious Talbiya to the east and the sprawling, mostly Muslim, Al-Baqa’a to the west. Hala, the youngest of the three children of eminent educator Khalil Sakakini, was born in the Old City. In her account of the various houses that her father had rented, she brings alive sites and neighborhoods in the now Israeli-occupied West Jerusalem and populates them with insightful, stirring, and sometimes funny anecdotes from when it was still Palestinian. At first, her dad rented the romantic windmill off King George Street –lovingly referred to as the cottage, al-koukh – which had belonged to the Greek Orthodox Church. During the next few years, they rented various apartments in the German colony from German Templars before finally building their own home in the middle-class Greek Orthodox community in Qatamon.

January 6, 1948, the day after the terrorist blow-up of the Semiramis Hotel, witnessed the first wave of forced exodus from Jerusalem’s western suburbs: Talbiya, Al-Baqa’a, and Lower and Upper Qatamon. Throughout the day following the attack, terror spread. Palestinian residents were seen carrying their belongings and leaving Qatamon for fear that their houses would be blown up while they were asleep. Those who had relatives still living in the Old City took refuge with them until order prevailed. Many others held out. The neighborhoods organized night patrols to keep watch and alert each other in case of danger. As the Zionist terror escalated, more and more people left Qatamon until almost all the Arab population had disappeared. Overnight, thousands of professional Jerusalemites found themselves homeless and jobless, crammed within the walls of the Old City, living with their parents and grandparents.

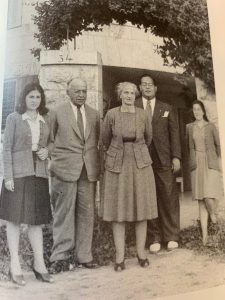

On April 30, less than four months later, Khalil al-Sakakini, with his daughters Dumia and Hala, fled for safety to Cairo. They were the last Palestinians to hold steadfast to their home in Qatamon. In her precious chronicle, Jerusalem and I, Hala al-Sakakini preserves the charmed way of life they had left behind. Erudite, sensible, and sentimental, the book chronicles Qatamon’s social life in the deteriorating political situation culminating with the fall of West Jerusalem in 1948.

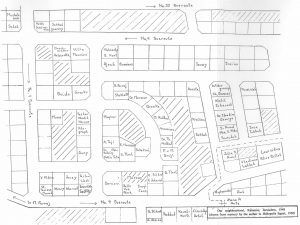

In Jerusalem and I, Hala al-Sakakini lovingly writes of her longing for Qatamon, her family, their friends, and their homes with red terracotta roofs surrounded by cypress trees, jasmine and honeysuckle bushes, flowering shrubs, and roses. Based on diaries, letters, and personal musings, the biography was redrafted in Cairo and finished in Ramallah.The diary, which she describes as a personal account, is a nostalgic reconstruction of a way of life she longs for. Written in English (as was customary for her generation and mine who were trained to pass the British matriculation exams), the book’s 150 pages are illustrated with many family photos and a hand-drawn map that pinpoints the homes, families, and shops in her immediate neighborhood.

Jerusalem and I draws a vivid picture of the way life in Qatamon used to be. We glean the cosmopolitan lifestyle of the period in Hala’s portrayal of the local – the exquisite characterization of her relatives, friends, and neighbors, the fuss and excitement in anticipation of Christmas and Easter, of the delicacies from Spinney’s, of the savory cheeses from the Greek delicatessen Zapheriades and the scrumptious cakes from Frank’s the German Templar bakery. In the style of Jane Austen, the book invites us to follow the interconnecting social relations. We are ushered into her social world composed of a litany of names whose memories linger in Jerusalem: Arnita, Awad, Tubbeh, Haddad, Farraj, Kreitem, Salfity, Sruji, Sfeir, Joury, Tleel, Kort, Ajrab, Damiani… As we leaf through the book and browse the family albums, a petit bourgeois, genteel way of life that has long since disappeared is brought to life.

Throughout the narrative of Jerusalem and I, the reader senses the depth of the trauma that Palestine and the Palestinians sustained. Victims of British Mandate oppression and helpless vis-à-vis the Jewish terrorist attacks, the direct danger and threat to life loomed large. Danger was imminent, and it was clearly present. As the tensions and threats escalated, social life centered on the radio, following the news and trying to locate the explosions and sniper exchange that rocked Jerusalem on an almost daily basis. Given her father’s sense of humor, fortitude, and charisma, neighbors gathered daily in their house for solace, strength, and well-being. Fear of the bleak future was dispelled with humor as they relentlessly held to their homes.

“Do we leave tomorrow?” was a question that became a common joke as they knew that sooner or later they would be forced to leave. The pitch of Jewish terrorist assaults and everyday fears take over the narrative after 1947. Throughout, the Sakakini family remained a source of strength for the few that stood their ground in their homes with one major preoccupation: waiting… waiting for the end of the internecine fighting and for the outcome of Jewish Haganah terror attacks, praying for the safety of loved ones and for the return of peace.

Believing the Arabic rhetoric, the classical Palestinian tragic flaw (hamartia), the neighbors huddled around Khalil al-Sakakini naively holding steadfast, waiting for the Arab armies to come to save them. No one came to their rescue: the emptying of West Jerusalem of its Arab residents was pre-arranged as a preliminary step to separate the area west of the river Jordan from Israel.

It is startling to note that throughout the book, the narrator, who is an educated professional and the daughter of the great Palestinian intellectual of the period displays no awareness of the various Zionist political parties nor of the various strategies to evacuate Palestine nor of the complicity of the Arab regimes in the division of Palestine. The Zionist Operation Nachshon, part of the plan to secure access to Jerusalem and evacuate the surrounding western villages, for example, is never mentioned, neither in her biography nor in that of her father.

Sadly, the Sakakini diaries of both father and daughter, which complement each other, reveal the tragic irony: namely, that the self-centered, personal preoccupations of the relatively privileged middle-class, cosmopolitan suburb-dwellers, both Christian and Muslim alike, inured them to the grievous threat posed by the Balfour Declaration and the role of the British Mandate in implementing it. Uppity and cocky, the educated middle class became marginalized, inadvertently accelerating the process of its own demise. Alienated from the overall social, political, and economic upheavals, ambivalent vis-à-vis the widening rift and intra-Palestinian civil disorder produced by the Husseini/Nashashibi political parties, they were ultimately ineffectual in responding to the international consensus on the need to create a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. The assimilation of Western humanist liberal aesthetics, values, and consumerism sequestered the Palestinians and rendered them individualistic, vulnerable, and defenseless.

“Reality” was misconstrued. The ensuing lacuna among educated Palestinian middle classes impeded their perception and appraisal of the imminent Zionist threat. They, with their savings, were the first to stampede outside Jaffa, Haifa, and other lost cities to initially comfortable hotels in Cairo, Beirut, and Damascus before they rented or purchased new properties in exile. With their exodus they left behind the uneducated rabble.

The underground terrorist Haganah, the core of the present-day Israeli army, targeted scrupulous Palestinians to spur panic and terror. Its end was achieved in various bombings in Jerusalem. In Hala’s narrative there is no mention of Jewish history in the making nor any account of the various political groupings. She is simply surprised that nice, civilized Europeans are capable of such atrocities.

The structural myopia, méconnaissance, of the Palestinian bourgeoisie was fostered by the misleading, highly distorted nationalist discourse and further confounded by the inter-Palestinian political rivalries between the Husseini and Nashashibi partisans. The Palestinian educated, professional middle class was misled by vapid rhetoric manipulated by local politicians seeking favor, power, and recognition of Arab foreign states who in turn had their own self-serving agendas. Concurrently, the inter-Palestinian conflict obstructed the development of a unified nationalist consciousness and ultimately a centralized administrative body. Consequently, they failed to set up their own intelligence centers that would research and systematize Zionist strategies in preparation for the takeover of Palestine. Apart from Abdel Qader Husseini who undertook preemptive action, Palestinian resistance remained sporadic and invariably reduced to retaliatory responses. The ensuing political chaos was augmented by the fact that the nationalist resistance parties were infiltrated by the rabble, undermining the credibility of the leaders and turning them into rabble-rousers.

From Qatamon, and the rest of the lost cities, the Palestinian educated middle class dispersed all over the world. The Nakba, in this context, was a major blow not only to the Jerusalem Christian community but to the Palestinian bourgeoisie, Muslim and Christian alike. It was the onset of the “brain drain” that led Jerusalem and other urban centers to devolve into backwater provincial towns. In the ensuing vacuum, the rabble assumed positions of leadership; the Robin Hood mentality in its negative sense has dominated the Palestinian sphere of political action.

The last days in Qatamon read like a tragicomic satire. Following the night of the Semiramis explosion, a neighborhood meeting was held at Khalil al-Sakakini’s home in Qatamon. The gathered men decided that they needed to protect themselves from Zionist terrorists. They had a few guns that they did not know how to use. As in a tragedy, we read with pity and horror the demise of the bourgeoisie in Sakakini’s chronicles. The first group dispatched to protect Qatamon produced frictions and problems with the residents that required Abdel Qader Husseini to interfere. They were replaced by the suave single guard, Mr. Abu Dayyeh (the Muslim guard from Dura), aided by a single assistant! Once he is shot down, the last residents are left defenseless.

On April 15, as the bombing intensified, Mr. Sakakini sent his library and manuscripts for storage in his sister’s house inside the Old City.

On April 30, at around six in the morning, Khalil Sakakini and his two daughters Dumia and Hala left Qatamon to take refuge in Cairo.They were the last Palestinians who held steadfast to their home in Qatamon. The road from Qatamon to Jaffa Gate had already been occupied by the Haganah and blocked. They had to flee from the back road through Beit Jala, past Hebron to Cairo. The trip took 13 hours.

Hala returns to visit her home and neighborhood following the defeat in the 1967 War and the total loss of Palestine. She describes her pain.

“We left our house and our immediate neighbourhood with a sense of emptiness, with a feeling of deep disappointment and frustration. The familiar streets were there, all the houses were there, but so much was missing. We felt like strangers in our own quarter.”

Al-huzon, nostalgic melancholy, permeates every step that Hala Sakakini takes. The specter of solitude hovers over each home as the residents of Qatamon abandon their homes for their lives; not a single family has been spared the wounds of death, injury, and grief. Nostalgia, melancholy, and an unfathomable sense of solitude; these thematics that we have come to associate with Jerusalem figure prominently in her account of the fall of Jerusalem’s western suburbs. The great diva Fairuz epitomized them in her songs of Jerusalem. Henceforth, Jerusalem has come to embody these feelings. Al-huzon dwells in Jerusalem.

By the early sixties, Jerusalem had developed the character now deeply impressed in me: a city of old people who cling to memories about a period of time in the past, when families lived together: a paradise lost and a civilization gone with the wind.