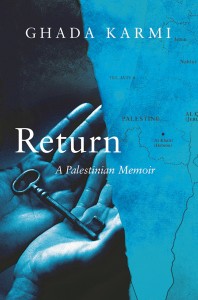

By: Ghada Karmi

Verso, 2015, 319 pages $30.00

Reviewed by: Mahmoud Muna,

The Educational Bookshop, Jerusalem

Written by the trained Palestinian doctor of medicine, writer, and political analyst Ghada Karmi, this is the long awaited sequel to her best-selling book “In search of Fatima – A Palestinian Story.” In the first volume, exploring her identity as a Palestinian having grown up abroad, she depicted her childhood that she spent from the first up to her ninth year in what was then Palestine, after which – as a consequence of the Nakba – her family emigrated to the UK, where they lived thereafter in a Jewish neighbourhood of London. In this new book Return – A Palestinian Memoir, she takes us on the rest of the story, describing how she returned to her place of birth to pursue her quest for identity and belonging.

Written by the trained Palestinian doctor of medicine, writer, and political analyst Ghada Karmi, this is the long awaited sequel to her best-selling book “In search of Fatima – A Palestinian Story.” In the first volume, exploring her identity as a Palestinian having grown up abroad, she depicted her childhood that she spent from the first up to her ninth year in what was then Palestine, after which – as a consequence of the Nakba – her family emigrated to the UK, where they lived thereafter in a Jewish neighbourhood of London. In this new book Return – A Palestinian Memoir, she takes us on the rest of the story, describing how she returned to her place of birth to pursue her quest for identity and belonging.

Indeed, she explains that “by 2005 [she] had lived in England for more than fifty years, and was fairly integrated and at ease in [her] adopted country. It was [her] home as much as anywhere could be. But [she] was of that generation of Palestinians who still retained a memory of the homeland (…) and still knew it as their real country.” She therefore applied for a job with the Palestinian Authority (PA), that was then in charge of both the West Bank and Gaza, and was attached as a consultant to the PA’s Ministry of Media and Communications in Ramallah.

Presenting her view on the events she witnessed and participated in over the period of time that she worked with the ministry, Karmi gives us the interesting perspective of a Palestinian having mostly lived abroad, of an activist in her country of adoption who comes back to her homeland in order to place her experience and skills in its service while looking for her own roots. However, the return may not have been as easy as she had hoped.

What is striking in Karmi’s new book is, as in her previous novel, her honesty, her sincerity, and the reality that she presents. Hence, she depicts her frustration when she considers the functioning of the ministry, the funding of which depends mostly on foreign aid and which is paralysed by internal rivalries. Her descriptions of the Wall and its destructive effects on human lives, of the situation in Gaza, or of her visits to Amman, where her father lives, also constitute instructive elements that enable the reader to better understand Palestine and Palestinians today.

This individual quest therefore reflects a larger reality: the effects of having been uprooted and of the changes that time and occupation have brought to Palestine. It is a very warm and personal memoir, beautifully written, unpacking the new realities in modern Palestine.

As she remembers a conversation that had taken place a few years in the past with one of her friends according to whom “Palestinians have to learn to let go,” Karmi recounts that she had replied “For us, the past is still the present.” This observation gives the entire book a bitter note, for the return she had so longed for was eventually made impossible by what she found; her “return” concerns a past that has, in fact, disappeared.