Emile Habibi was born on August 29, 1922, in Haifa, and lived to become one of the best-known authors in the Arab world. He started his early adult life working in an oil refinery while pursuing by correspondence a degree in petroleum engineering from London University. He never graduated but rather moved on to work at a radio station. During the Mandate era he was a leader of the Palestine Communist Party and supportive of the 1947 partition plan. During the Nakba he bravely stayed and fought in Haifa – at a time when many of his contemporaries fled or were forcefully expelled. After the Nakba, he became a leader in the League for the Liberation of Palestine that became the Israeli Communist Party (Maki), but in 1965 he broke off and co-founded Rakah to protest increasingly pro-Zionist tendencies within the party. The Soviet Union recognized Rakah as the official communist party, denouncing Maki for having defected to the bourgeois-nationalist camp. Habibi served in the Knesset for many years both in the 1950s and again throughout the 1960s.

In the 1950s, Habibi became editor-in-chief of Rakah’s Arabic-language newspaper Al-Ittihad (The Union), which called for a secular, democratic, multi-ethnic state and the unity of Arabs and Jews. With the literary supplement Al-Jadid (The New), Al-Ittihad promoted the emerging Palestinian resistance poetry of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Habibi started to write short stories during this time partly in order to document Palestinian existence through the creation of literature and to resist Israeli attempts to eradicate Palestinian identity. His works explore the conflicting feelings and loyalties of Arabs who, like him, were able to stay in their homeland that had become Israel. Irony is one of the main features of his work whose popularity extends throughout the Middle East. Of his seven novels, The Secret Life of Saeed the Pessoptimist (Al-Waka’i al gharieba fi ikhtifa Said Abul Nahs al-Mutasha’il) is the most famous and includes elements of tragedy, comedy, and fantasy. Habibi explains the struggle of Palestinians who live in Israel, adopting the viewpoint of the stock-character villain Saeed who is pulled into political action without intention. The novel has been translated into more than a dozen languages, including Hebrew.

In 1990, the Palestine Liberation Organization granted Habibi its highest honor, the Al-Quds Prize. When in 1992, he received the Israel Prize for Arabic Literature, his acceptance caused quite a stir among the Arab academic community. Habibi commented on the controversy by noting: “A dialogue of prizes is better than a dialogue of stones and bullets.” His acceptance of both prizes reflects his belief in the possibility of coexistence, a belief that is not shared by everyone. But Habibi asserts: “[My accepting the prize] is an indirect recognition of the Arabs in Israel as a nation. This is recognition of a national culture. It will help the Arab inhabitants in their struggle to retain roots in their land and win equal rights.”

In 1956, Habibi moved from Haifa to Nazareth, the place where he was to spend the rest of his life. He passed away in 1996, at the age of 74. His will requested that he be buried in Haifa, the town he had defended during the Nakba, and that his tombstone include the phrase “stayed in Haifa.”

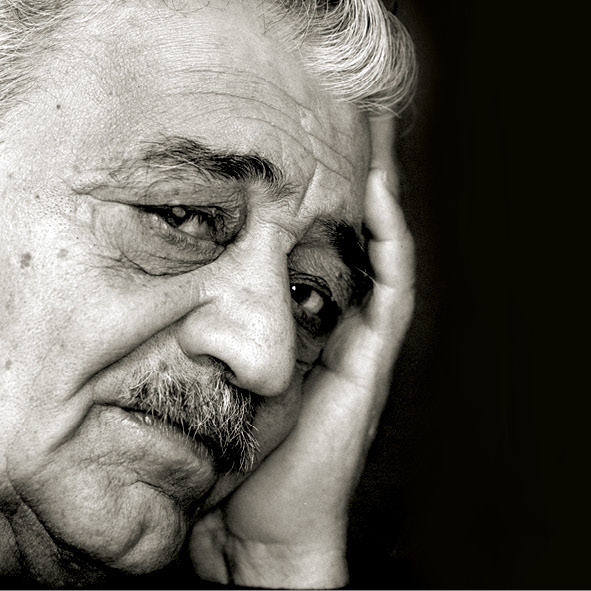

Personality of the Month