Lessons from My Father

By: Diana Safieh

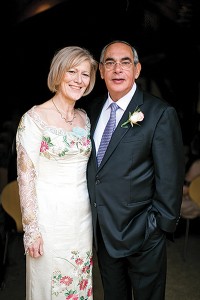

There is a side of Afif Safieh, my father, that cannot be accessed through ordinary means such as the Internet. If all you are after is a rundown of his CV, then just Google him, or read his book if you would like to learn more about his politics. I am fortunate enough to have grown up with him as my live-in hero and would like to share the lessons he taught me. These lessons have served me well, and I believe that they are also the principles that have guided him throughout his career. So please allow me the privilege of being sentimental at times. And given that he was not previously informed about this article, I would also like to apologize to him if this tribute makes him self-conscious.

There is a side of Afif Safieh, my father, that cannot be accessed through ordinary means such as the Internet. If all you are after is a rundown of his CV, then just Google him, or read his book if you would like to learn more about his politics. I am fortunate enough to have grown up with him as my live-in hero and would like to share the lessons he taught me. These lessons have served me well, and I believe that they are also the principles that have guided him throughout his career. So please allow me the privilege of being sentimental at times. And given that he was not previously informed about this article, I would also like to apologize to him if this tribute makes him self-conscious.

The theme for this month’s issue is diplomacy, and nothing tests this art like raising two daughters. Although he was already abundantly diplomatic before Randa and I came into this world, we would still like to take some credit in the development of his negotiating, mediating, and peace-making skills. I still don’t know how he managed to convince me, at age six, that it was my idea to choose books instead of that pony. But I am grateful to the man who taught me that education is the ultimate, the only thing you can take with you wherever you choose or are forced to go. Lesson number one: always be open to learning more.

Like so many second-generation Palestinians, many of whom, like us, are of mixed heritage, my sister and I had to navigate the complexities of being culturally, physically, and generationally different from both our parents, while living among customs that were neither theirs nor ours. Because of my father’s career, we also moved from country to country fairly often. Having been denied the right to return to Jerusalem after 1967, when he was just seventeen years old and studying in Belgium, my dad showed us that developing resiliency and the ability to adapt to new situations and challenges should only ever be viewed as an advantage. Lesson number two: it is not a case of belonging neither here NOR there, but of belonging here AND there.

My father has also taught me a perhaps surprising amount about what it means to be a woman. While preparing us for the specific constraints we would face as women (ambitious and opinionated ones at that), he always instilled in us the conviction that we have just as much right as boys and men to achieve whichever life goals we desire (apart from one, to return to our homeland, but that is not gender-specific, and my dad is still working on this). This should not be viewed as an enlightened perspective, yet sadly we still live in a world where women face glass ceilings, walls, and locked doors in many aspects of life. Lesson number three: do not limit your ambitions to what society dictates is possible for your gender, age, religion, or ethnicity.

I remember the time when Randa came home and told us that she had made a new friend whose parents were Zionists. My dad’s reaction was to tell her to “never let that be an issue between you.” Far more accepting of people than I could ever hope to be, he holds the belief that those who respect the basic human rights of all people should be able to find mutual ground, be it in the political sphere or in friendship. Lesson number four (and this one is a difficult one to abide by): always judge people by their own actions, beliefs, and words, and not those of their family, people, or nation.

On the issue of his own faith, having been brought up in a Christian family, my father will be the first to say, “I have my doubts, but also doubts about my doubts.” Although I seem to have inherited those doubts, the Christian ethos of serving humanity was also passed down. Regardless of what we believe happens after this life, we can all agree that we are here for a short time, and if that time is not used to improve the situation of one person, one people, one cause, then it risks being wasted. Whether it was as president of the General Union of Palestinian Students, visiting scholar at Harvard, general delegate to the United Kingdom, the Holy See, the United States, or Moscow, it is not just because I am his daughter that I say he has fought tirelessly to raise awareness about the plight of the Palestinian people. He has been faultless and irreproachable in representing us all, regardless of our various religious or political views.

Solid guidance from my father gave me the will and strength to pursue a career in the humanitarian sector. I have the privilege to work for the London fundraising branch of St John of Jerusalem Eye Hospital Group, the only charitable provider of eye care in the occupied Palestinian territories. From the time I was a child, he taught me that every job would have elements that are boring or difficult. These tasks are infinitely more bearable if it is for a cause you love. As I have just been admitted as a Serving Sister in the Order of St John for contribution to the hospital, the biggest honor, in fact, is that I will be joining my father and great uncle as members. They were also made members of the Order of St John for the support that they have given to the hospital. As we like to joke around the dinner table, my father will now also be my brother. Lesson number five: always do something significant.

In addition to mentoring me, my father has advised and guided many young Palestinians who now hold positions of positive influence and change. I would list them all if I hadn’t been set a word limit.

Those of us lucky enough to know him personally can confirm that he conducts himself in his private life as he does in public. He handles difficult situations, and difficult people, with dignity, grace, and respect, always finding common ground and a means of communicating effectively. Although the life lessons mentioned have been duly noted, I am still working on learning how to apply them one hundred percent of the time. Given more time with my father, I hope to succeed.