Before the British Mandate, passports of Palestinian women did not include personal identification photos. In order to confirm the identity of a woman passport holder, officers used to simply call out the woman’s name and that of her husband, or of her father if she was single. After photography was discovered with the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839 and became an enormously significant manifestation of modernity, it spread across the Arab cities in the second half of the nineteenth century. In fact, at that time, the Middle East and Palestine were among the most photographed regions worldwide, as photographers from around the world came to visit and document this area that abounded with picturesque scenes, and Ottoman photographers delighted in taking photos of the sultan and his military officials.

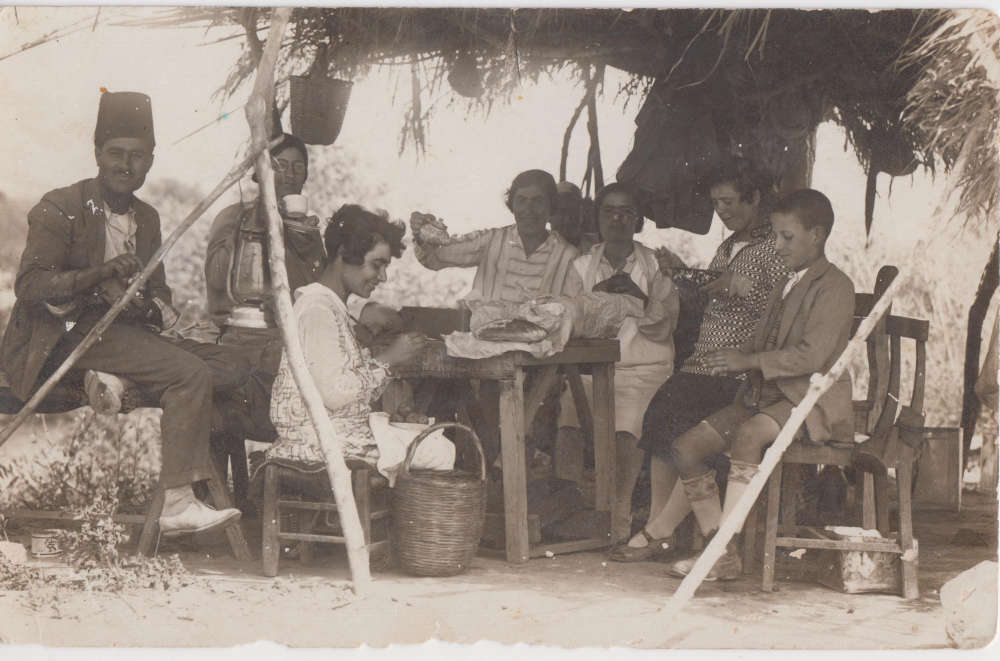

taken by Karimeh Abboud in 1926.

The first school of photography in the Arab world was established in Jerusalem by Yessai Garabedian in the 1860s. In his position as bishop, known as Esayee of Talas, Garabedian could not engage in photography himself, but he could teach, and his studio taught the most important photographers of Palestine at that time. Palestinian photography, however, was almost entirely monopolized by men until Karimeh Abboud broke the norm.

Karimeh was born in Bethlehem in 1893, to a family of Lebanese descent. She started to engage in photography in 1913, after her father had given her a camera for her 17th birthday, and she began to take photos of natural scenery, cities, historical monuments, family members, and friends. She received instruction in the craft of photography from an Armenian photographer in Jerusalem. When Karimeh studied Arabic literature at the American University of Beirut, she took photos of archaeological sites and may have received instruction from local photographers, as Beirut was also an important center of photography. Back in Palestine, Karimeh opened her first studio as a professional photographer. Her photographs of women of Bethlehem encouraged conservative families to photograph their women without embarrassment, and she was soon able to open a photo coloring studio.

When the family moved to Nazareth, Karimeh opened a studio there. As the first woman photographer, her work was in high demand, and eventually, she was able to establish four photography studios, located in Nazareth, Bethlehem, Haifa, and Jaffa. She drove her car from city to city, making her also one of the women pioneers in the Arab world to obtain a driver’s license. She travelled to Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan on working missions, mostly shooting personal portraits. However, her work also documented towns with their churches and mosques, archaeological sites, and landscapes.

An important personal trait of Karimeh was her interest in children and social occasions. She would leave her work in the studio to photograph children on the streets. She also took photos of social celebrations and events. Whereas most professional photographic work at the time was done in studios, carefully designed, and frequently with the intention to create an image that would leave the impression of an elevated reality and give the subject increased status, Karimeh would take her photos in people’s homes, setting up makeshift sceneries and backdrops. This also had an effect on the general mood of her subjects, as Karimeh’s portraits are frequently characterized by an element of spontaneity.

Karimeh passed away in 1940. There is no doubt that she is among the most important personalities to bring about change in the field of photography in Palestine. She focused on Palestinian and Arab women in her photography and helped to change perceptions by showing that Palestinians are not simply nomads living in tents. If one compares fashion and hairdos in Paris during her time, one will find photos of confident Palestinian women with similar styles in Palestine, proving that Palestine kept up with modernity. This historic documentation would not have been possible or available without the work of Karimeh. And it is important to consider Karimeh’s context: We are not talking about a photographer in London or New York; this is a Palestinian woman at the turn of the twentieth century who dared to break stereotypes in the Middle East.

Ten years of research and interviews conducted by Ahmad Mrowat concluded that more than 4,500 studio and outdoor photographs taken by Karimeh Abboud are extant today. Three cameras were used during Karimeh’s career. About 3,500 of these photographs along with original cameras are in the possession of Ayman Metanis who currently resides in Canada. The location of the remaining photographs is still unknown.