The mere name, Al-Quds, triggers an emotional, affectional upsurge in every Muslim heart and mind, wherein nostalgia, piety, and the love of God and his prophet Mohammed meet. Pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the footsteps of the Prophet Muhammad is a spiritual journey leading to a process of religious transformation, and touching the deepest aspects of the human spirit. It is a mystical rite of passage that promotes one’s personal connection with God.

The lore of Jerusalem as the axis mundi –the symbolic center of the world where the four compass directions meet– reverberates throughout Islamic history. Inspired by Prophet Mohammad’s Night Journey to Jerusalem to connect with God, the pious believe that travel and correspondence between Heaven and Earth, between the higher and lower realms, is possible at Al-Aqsa Mosque. Communication from the lower realms may ascend to the higher ones, and blessings from the higher realms may descend to the lower realms. Jerusalem functions as the omphalos (navel), the world’s point of beginning, inflaming Muslim passion with yearning for the holy city. The belief that contact with God, which in Mecca had been mediated by the Archangel Gabriel, took place exclusively in Jerusalem gives the Holy City a distinctive sacred status; it represents the hallowed ground where all biblical prophets who have connected with God reside. Alternately, Jerusalem is believed to be a piece of Heaven on Earth, the closest place to Heaven and the site where the Day of Judgment will take place, and where the righteous and pure of heart shall convene.

♦ Muslim spiritual tourism highlights Palestinian Sufi heritage. The travel itineraries include sanctuaries, medieval theological colleges, Sufi hostels, and residential quarters, where Moslems from heterogeneous ethnic backgrounds have resided over the past millennia. These iconic sites symbolize fundamental aspects of Muslim spirituality: a culture, a history, and an outlook that embody esoteric spiritual mystical trends in Islam.

Jerusalem is a constituent of Muslim faith. The Prophet Mohammed ordains travel with the exclusive desire to pray in Jerusalem, Mecca, and Medina. “Journeys should not be taken (with the intention of worship) except to three mosques: the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, my mosque in Medina, and Masjid Al-Aqsa in Jerusalem.” The relationship of the three holy cities, it must be stressed, is not of a hierarchical order, but of a dialectic nature based on their value as symbolic expressions of the eruption of the sacred in Islam.

♦ The tension between inner esoteric Sufi Islam and outer exoteric orthodoxy underlies the alternately high valuation and undervaluation of Jerusalem throughout history. Within the context of puritanical fundamentalism, tenets of faith are reduced to prescriptive normalizing public rituals that co-opt one’s direct experience of God. The Sufi quest to connect individually with God is judged as a presumptuous, arrogant transgression and act of hubris. The vacillating value of the Dome of the Rock as a mere architectural masterpiece or as the expression of the mystical locus of the sacred is symptomatic of this chronic crisis in the history of Muslim thought.

By enjoining Muslims to visit these holy cities and associated holy shrines, Prophet Mohammad recognized the idea that we are all to form our own relationship with God. The belief that we are able to have that instant, direct, and personal spiritual experience of and communication with God underlies the mystical esoteric theology that is often opposed by orthodox Islam. Muslim mysticism can best be thought of as a constellation of distinctive Sufi practices, discourses, texts, institutions, traditions, and experiences, which have been variously defined by different Sufi schools (tariqa).

Muslims and mainstream scholars of Islam define Sufism as simply the name for the inner or esoteric dimension of Islam, which is supported and complemented by the outward or exoteric practices of Islam, such as Islamic law (shari’a). In this view, it is absolutely necessary to be a Muslim to be a true Sufi because Sufism’s methods are inoperative without Muslim affiliation. This can be conceived of in terms of two basic types of law (fiqh):laws concerned with public actions, and laws concerned with one’s own actions and qualities. The first type of law consists of rules and rituals pertaining to worship, transactions, marriage, judicial rulings, and criminal law—what is often referred to, broadly, as qanun. The second type of law, which governs Sufism, consists of rules about repentance from sin, the purging of surreptitious qualities, and how to inure oneself against human susceptibility to carnal material desires. The Prophet was the model of spirituality for the world. In the Sufi interpretation, the Prophet Muhammad is perceived as the first Sufi because of his exemplary God-consciousness, deep spirituality, acts of worship, and love for Allah.

Prophet Muhammad’s central position in Sufism is closely related to the belief that Allah sent the Prophet as the source of knowledge par excellence of the Quran, tafsir (exegesis), rhetoric, fiqh (jurisprudence), and Hadith. All that the Prophet said and did is known in Arabic discourse as Sunnah. After the Prophet’s death, various scholars studied and propagated each of these sacred expressions in specialized discourses within distinct fields of study that came to be known as the Islamic Sciences (علوم الاسلام). It is recognized that Imam Abu Hanifah preserved the science of fiqh (jurisprudence), and after him thousands of scholars continued in his footsteps. Hence these scholars are believed to have preserved discursively the fiqh of the Prophet. Similarly Imam Bukhari and the other famous scholars of Hadith preserved the maxims, sayings, and life of the Prophet, in other words, the Sunnah. The scholars of tajweed (a method of reading the Quran) preserved the recitations of the Prophet, and the scholars of Arabic grammar preserved the language of the Prophet.Thus, the Prophet was the model of spirituality for the world. His exemplary comportment, as well as his love for, and connection with Allah were preserved and propagated by an Islamic science called tasawwuf. The aim of the scholars of this discipline was purification of the heart and development of a heightened consciousness of Allah through submission to the Shariah and the Sunnah.

Gnosis, or the individual quest to love, know, and connect with God, is founded on the orthodox concept of dhikr, or remembrance of God. The injunction to conjure God’s presence constantly is replete throughout the Quran. Faith and ritual conjoin in the Sufi practices of dhikr, which allow the practitioner to dissolve human consciousness, disengage from material earthly distractions, and induce a state of grace in which God’s presence is conjured and a connection established with the divine. A diversity of Sufi schools of thought and practices have been deployed to achieve this ecstatic state of dhikr, which often takes the form of rhythmic chanting of the holy name. Sama’ (listening closely) is another means of disengagement from the material world through music and dance, of which the whirling dance of the Mevelevi dervishes is a prime example. Meditation is another way of conjuring God’s presence. Visiting holy places to absorb barakah, or grace, is of paramount importance. In this respect the lore of Jerusalem and its mystical connection with the Prophet’s miraculous Night Journey acquires special allure for Muslims in general, and Sufis in particular. Sufis, mystics, and spiritualists travel to Jerusalem/Al-Quds to touch and see the physical manifestations of their faith and confirm their belief in God.

During the Muslim lunar month of Rajab in the year 620 AD, almost one and a half years before Prophet Mohammed’s Hijra (migration) from Mecca to Medina, the symbolic event of Isra’ and Mi’raj (the Night Journey and Ascension) occurred. The Prophet Mohammed made a night journey from Mecca to Jerusalem and thus ascended to the heavens. Whereas the horizontal voyage to Jerusalem is referred to as Al-Isra’, the vertical ascension to heaven is called Al-Mi’raj, which is derived from the word arj (عرج), to ascend, and refers to Prophet Mohammed’s ascension to the heaven to seal God’s covenant with the Muslim Prophet. As it says in the Quran, “Glory be to Him who made His servant go on a night from the Sacred Mosque to the remote mosque of which we have blessed the precincts, so that we may show him some of our signs; surely He is the Hearing, the Seeing.”1

Prophet Muhammad’s overnight stopover in Jerusalem is of pivotal symbolic and theological significance. The story of the Night Journey is full of miraculous legends and symbols of special allure to Sufis. The angel Gabriel provided the Prophet with the legendary buraq that whisked him at lighting speed from Mecca to Jerusalem. Legend portrays a magical animal, bigger than a donkey and smaller than a mule, with lightning speed—hence the name, Al-buraq, an anagram of the word barq, Arabic for lightning. There, it is believed that the Prophet stood at the Sacred Rock (Al-SakhrahAl-Musharrafah) and then ascended to the heavens where instructions related to prayer were revealed. In Jerusalem, he meditated in the Cave of Souls inside the Holy Rock, met with the biblical prophets who are mystically perceived as residing in Jerusalem, and led them in prayers. After these experiences the Prophet returned to Mecca astride the mysterious buraq.

Al-Mi’raj, as a symbolic expression of the sacred, remains shrouded in evocative mystery, around which folk culture has deployed fantastic narratives. According to folk legend, the Holy Rock, from which the Prophet rose to the heavens has changed and has come to assume a symbolic function as a sign of that mysterious Night Journey. That night, according to the Qur’an, God blessed the rock and its environs. Blessed and sanctified by God (الذي باركنا حوله), the rock assumed a new identity as the “Holy Rock” (الصخرة المقدسة). Roman Jerusalem, Aelia Capitolina, assumed its new Muslim identity as the City of the Holy Rock, Bayt Al-Maqdis, from which the present-day appellation Al-Quds, the Holy Rock, is derived.

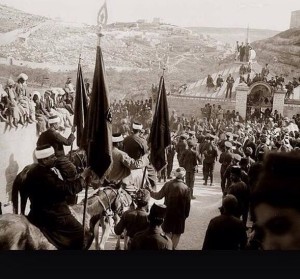

An overpowering sense of sacred presence permeates the precincts and comingles with the architectural beauty of the Noble Sanctuary to endow the location with a transcendent quality. Throughout history, mystics, overwhelmed by the great spirituality that Al-Aqsa Mosque exuded, settled in Jerusalem. Their successors form the social fabric of Jerusalem, each family distinguished with its own banner indicating the Sufi sect they belong to. Stored in the house of the grand mufti on Aqabet Al-Bayraq Street, these banners are ceremoniously hoisted in official Sufi processions, such as Nabi Musa and for funerals, a tradition dating back to Saladin.

The local patrician Sufi families and Sufi expatriates bequeathed us their respective endowments, zawiya and khanqah. Among the expatriates, Al-Moghrabi is a common family name and refers to anyone whose grandparents came to Palestine from Morocco where they lodged in their endowments, living quarters, and khanqah, which were bulldozed to make room for the huge empty courtyard comprising the Wailing Wall. Similarly Al-Afghani, Al-Bukhari, and Al-Naqshbandi are family names ascribed to Jerusalemites whose Sufi ancestors, over the past 500 years, came on pilgrimage to Jerusalem from Uzbekistan, Bukhara, or Afghanistan and took up residence in their respective zawiya adjacent to Ecce Homo. Sunni Muslims from diverse ethnic backgrounds and from various Sufi schools of thought, enthralled by the holiness of the city, settled in Bayt Al-Maqdis. Similarly, Muslim Nigerians from the Hausa, Fulani, Bergo, Kalambo, Salamaat, and Berno tribes settled following their pilgrimages to Jerusalem within the premises of Ribat Mansour and Ribat Al’el Din, adjacent to Bab Al-Majlis the main entrance on the northwestern side of Al-Aqsa. Both in Mecca and Jerusalem they are generically referred to as Takarnah(singular Takruniالتكارنه) in contradistinction to the Arabic-speaking Sudanese community.

Jerusalem exudes great allure for all Muslims alike. The Sufi pilgrim to Jerusalem invariably belongs to a halaqa, a circle or congregation, each of which belongs to specific tariqah (order), which is formed around a master. During their extended sojourn in Jerusalem, the Sufi pilgrims, known also as dervishes, are received, housed, and provided with spiritual guidance by his or her respective ethnicity-affiliated zawiyeh or ribat. Each community can find spiritual guidance under the sheikh who is also the head of the Sufi tariqah that was associated with its respective country of origin and spoke its mother tongue. These zawaya (plural of zawiyah) and arbitah (plural of ribat) and khanqah,or residential-cum-spiritual quarters, further enriched Jerusalem’s allure as a pilgrimage center where various Sufi schools and theological colleges thrived. Dispersed throughout the Old City, the grandiose edifices, medieval theological colleges, zawaya, ar’bitah, khanqah, mausoleums, decorative water fountains (sabil), public kitchens, and diverse endowments form a virtual archive of a long train of princes, emirs, kings, and religious personalities who immortalized their names by their association with the Holy Rock enshrined under the golden dome of the Noble Sanctuary.

Notwithstanding the current tense situation, the Israeli siege and blockade imposed on Jerusalem, and the constant incursions, closure, and denial of access for Muslims and Palestinians in general to Al-Aqsa Mosque, the pilgrimage to the Noble Sanctuary, as a transcendent experience, remains an elusive dream.

The first view of the Dome of the Rock is visionary. The beauty of the Noble Sanctuary is astonishing. The architecture evokes the exhilarating feelings of awe, delight, and admiration. Its emotive splendor assuages existential loneliness and stimulates intimations of the infinite. Its immensity, lyricism, and harmony trigger the feeling of the sublime. The beauty of the Noble Sanctuary is accentuated by light. But neither the bouncing light nor the tenebrous shadow outshines the form of the sanctuary to the degree that it can obliterate the sight of the monument. Instead, the imagination is moved to awe and wonder. Tears fall copiously from the eyes of Muslim visitors to Al-Aqsa Mosque. The sight of the Noble Sanctuary and the Blessed Rock, Al Quds, is a moment of great intensity.

» Dr. Ali Qleibo is an anthropologist, author, and artist. A specialist in the social history of Jerusalem and Palestinian peasant culture, he is the author of Before the Mountains Disappear, Jerusalem in the Heart, and Surviving the Wall, an ethnographic chronicle of contemporary Palestinians and their roots in ancient Semitic civilizations. Dr.Qleibo lectures at Al-Quds University. He can be reached at aqleibo@yahoo.com.

1 Qur’an, Sura 17 (Al-Isra), ayat 1.