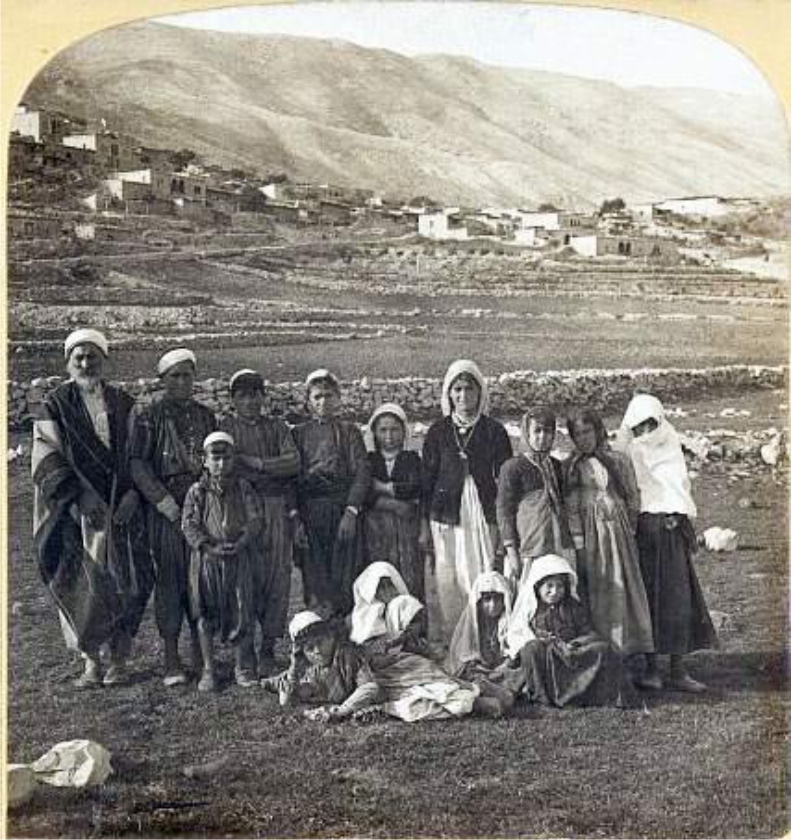

The indigenously Palestinian nature of the Galilee (al-Jaleel), a geographic region of Greater Syria, cannot be disputed, since for many successive centuries it has been dotted with hundreds of human settlements occupied by Arabs of varying social, sectarian, and ethnic backgrounds. The Galilee has been a deep and integral part of my homeland, Palestine. When in 1266 Bilad al-Sham (Greater Syria) came under Mamluk rule, it was divided into six administrative units, each called a mamlakah (kingdom). Mamlakat Safad constituted the Galilee; located in northern Palestine and in southern parts of the modern-day Lebanese Republic, it included ten districts. For the purpose of this article I shall focus on two of these districts, the Akka District and Al-Shaghour District, the latter of which held the areas Shaghour Arrabeh (in the south) and Shaghour al-Bi’neh (in the north). Shaghour al-Bi’neh included 16 villages, of which Al-Rama, or Rameh (my village) was one.i I shall follow the thread of continuity in Galilee through the continuous existence of my village over the past 750 years. Since 1970, I have been involved in studying my village and other Palestinian villages in the Galilee, focusing in particular on the processes of their transformation as they were oppressed and dismembered by external forces of occupation, most specifically the latest Zionist occupation of 1948ii.

The abundant olive trees in the valley below Rameh are known as umdan roumi (mature Roman olive trees), and their average age of 2,000 years has granted Rameh a historical reputation as “the land of olives and olive oil.” Rameh has existed continuously since the Mamluks ruled over Greater Syria, throughout the Ottoman rule over the entire Arab region that began in 1516, during the British Mandate rule over Palestine that culminated in the Zionist rule over the Galilee and most of Palestine, surviving the destruction of many villages in 1948. Gradually and over time, the Palestinian inhabitants of Rameh have built their homes on higher and higher ground, at the foot of Mount Heydar, which overshadows it and provides protection. The sea of olive orchards in the valley has constituted the cash crop for the inhabitants of Rameh, and the orchards have been cared for and maintained by generations of my ancestors as well as by those of other villagers. Over successive historical epochs, our olives and oil constituted the main item for commercial trading with what has become Lebanon. It is recalled through oral narrative that merchants from Lebanon and Syria used to come to Rameh before the beginning of the olive season to negotiate a price for the product even prior to its maturity.

Immediately following their occupation of the area, the Ottomans changed the Mamluk classification of the regions under their control. Mamlakat Safad, for example, became Sanjaq Safad and subsequently comprised five nahiyah (districts). Among them was Nahiyat Akka, which encompassed 53 villages, including Rameh.

The first population census was conducted by the Ottomans in 1526, ten years following their occupation of the region, and it showed that of the 53 villages listed in the Akka (Acre) District, 51 villages had Muslim populations. It should be kept in mind that the Ottoman census did not distinguish between Sunni, Shi’a, or Druze Muslims; all were lumped together into one category as Muslims. Thus Rameh, in 1526, was deemed a Druze village. As I was growing up, however, the composition of my village hovered at roughly two-thirds Christian and one-third Druze. Historical records show that the social components of my village have changed over a period in excess of 700 years, depending on the economic and political circumstances that were imposed. As an illustrative case in point, the main and sole component that distinguished my village from the beginning of Ottoman rule until the end of the eighteenth century was the presence of Al-Muwahiddun al-Duruz (Unitary Muslims).

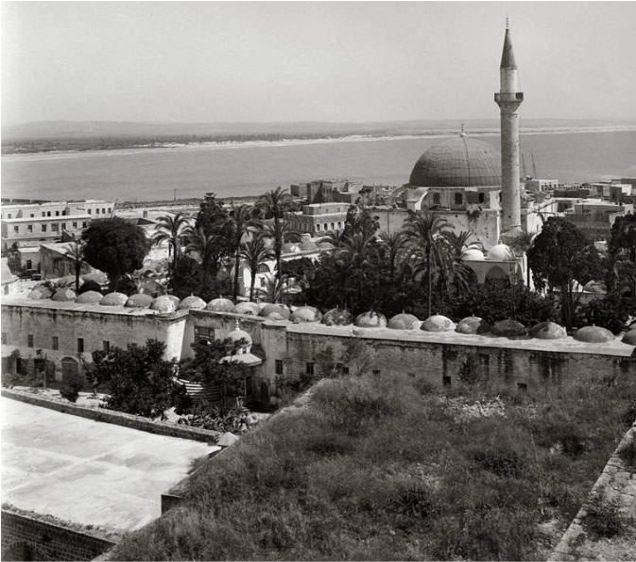

Soon after they established their rule over Greater Syria, the Ottomans engaged in the rejuvenation of the economic commercial environment in Galilee, particularly through the development of the Akka seaport. Such efforts started with the autonomous rule of Emir Fakhr al-Din al-Ma’ani al-Thani (1572–1635) and expanded further under the autonomous rule of Dhahir al-Omar al-Zaydani (1690–1775). Relations and agreements of international trade were developed with Europe, particularly Italy and France. Palestinian and Arab agricultural products from the Galilee and the entire Bilad al-Sham constituted raw cotton, linen, silk, woven cloth, grains, and more. These products were in great demand in European capitals and constituted major items of export throughout the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The promise of booming commercial relations with European countries prompted the ruling Emir Dhahir al-Omar al-Zaydani to encourage Christian and Jewish families from Lebanon and Syria with experience in commerce and finance to settle in the Akka region, enticing a wave of immigration.

The savage and tyrannical rule of Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar (who governed Akka from 1776 to 1804) applied an oppressive policy, blackmailing merchants by all means possible, confiscating their money, and persecuting the elite class, particularly Christians and Jews. This new situation forced many merchants and farmers to leave Akka for villages in the upper Galilee, southern Lebanon, and Jabal al-Duruz in Syria. Thus a new wave of emigration, this time in the opposite direction, was inaugurated. In the wake of these policies, the social and sectarian structure in Rameh was altered again during the first half of the nineteenth century. New Christian components began to surface when Christians with capital began to purchase lands with olive groves from the original Druze owners, establishing themselves firmly as legitimate components of Rameh Village.

With the 1948 Nakba and the Zionist occupation of the Palestinian Arab Galilee, as well as the destruction of more than 450 Palestinian villages, the surviving population was largely forced to flee outside the borders of historical Palestine. However, in some cases, Palestinians were displaced and relocated to surviving villages inside Palestine. Thus the majority of the population of the destroyed neighboring villages Kufr ‘Inan and Faradyeh (whose inhabitants were Muslim), and Iqrith (whose inhabitants were Greek-Catholic Christians) was resettled in Rameh as new refugees.

As mentioned above, Rameh was a farming community that relied primarily on olives and olive oil as its main cash crop, supplemented by some grains grown mainly for subsistence. Concerning artisanal and agricultural activities, historical records from the first Ottoman census indicate that 500 years ago Sanjaq Safad had 21 silk-spinning wheels, two of which were in Rameh. Furthermore, Sanjaq Safad featured 135 olive and grape presses, 24 of which were in Nahiyat Akka, and 92 water-run, stone flour mills, 14 of which were in Nahiyat Akka. Thus the indigenous inhabitants of the Arab Galilee villages have been economically and commercially active for at least 2,000 years, planting olive trees and supporting and feeding themselves with their homegrown agricultural products. Like the other Galilee villages, Rameh was an integral part of the indigenous configuration of this region, hundreds of years before it was re-occupied by Zionist forces on October 30, 1948.

Indigenousness, however, is no guarantee that the occupiers will not endeavor to alter the nature of the geographical and human space; indigenous Galilee, with its persisting Palestinian character, constituted a severe irritant to Ben Gurion beginning in October 1948. Relentless attempts to Judaize Galilee, at least during the past 70 years, have never stopped. But our presence in indigenous Galilee is neither an historical accident nor the fulfillment of a mythical divine promise; it is a cumulative testimony of our solid thread of human and natural history that has been grounded persistently in the rocks of al-Jalil!