Even today, Israeli government propagandists still claim that its 1967 occupation of the West Bank and Gaza (WBG) has brought benefits to the occupied population, especially in the field of health. As recently as 2014, David Stone, a professor at the University of Glasgow, produced a paper entitled “Has Israel damaged Palestinian health? An evidence-based analysis of the nature and impact of Israeli public health policies and practices in the West Bank and Gaza.” In the study, notably published by the British Israel Communications and Research Centre (BICOM), Stone argues that Israel has not damaged the health of the Palestinians of WBG and that, on the contrary, health in WBG has improved steadily since 1967 due to Israeli policy and practice over the course of the occupation.

It is true that, according to the general indicators, the health status of the Palestinians in WBG has improved since 1967. This, incidentally, is a worldwide trend, especially in Asia and Africa, mainly due to improved education and the rapid progress in medical and scientific development during the second half of the twentieth century. However, except for a limited number of positive but ultimately self-serving practices, this improvement has not been due to Israel’s generosity or benevolent occupation! Rather, as will be outlined below, most of the improvement in health status in WBG during the years of frank occupation (1967–1993) was a result of the efforts and determination of a resilient Palestinian community and the principled support and solidarity of certain sections of the international community.

♦ In 1985, the budget for government hospitals in the West Bank was US$8 million, of which three million were spent on the treatment of Palestinian Arabs who were transferred to Israeli hospitals. During the same year the budget of one Israeli hospital (Ichilov) was six times the amount allocated to all nine government hospitals in the West Bank. (UNCTAD, 1994)ii

Following the June war of 1967, Israel was required by international law to assume responsibility for health (and other) services in the recently occupied West Bank and Gaza. During the early days of the occupation, responsibility for health care was nominally shifted from the Israeli Ministry of Health to the Military Government and then to the Israeli “Civil” Administration, under the auspices of the Ministry of Defense. In reality, it has been well documented by several UN organizations (including WHO and OCHA), human rights agencies (including MAP-UK and Israeli Physicians for Human Rights), and others (including the Lancet) that during the first 25 years of the occupation (1967–1992), the Israeli-run government health services in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) were intentionally starved of adequate funding, leading to significant shortages of staff, hospital beds, medication, and essential specialized services. During that time, Israel aimed only to maintain standards of public health and curtail infectious and communicable diseases; it did not attempt to develop health services beyond primary care. Palestinians needing secondary or tertiary care were thus forced to depend on expensive health services in Israeli hospitals.

Prior to 1967, the health status of the 1.25 million people in the OPT (750,000 in West Bank and 500,000 in Gaza) had been rapidly improving through a collaborative effort between the then responsible governments (Jordan in the West Bank and Egypt in Gaza) and Palestinian NGOs and UNRWA, whose combined efforts aimed to address the adverse effects on public health which resulted from the 1948 war. For the large refugee population that was exiled mainly to WBG (but also to neighboring countries), UNRWA, supported by Palestinian health activists, had been successfully implementing health and education programs that were bearing fruit for the population as a whole.

Transformed into a nation of refugees, the Palestinians themselves were also eager to acquire new “transferable” skills through education, allowing them to use those skills wherever they found themselves, thus many studied medicine, nursing, or other health-related disciplines. By the time Israel occupied and unilaterally annexed East Jerusalem in 1967, there were already five well-established hospitals: Augusta Victoria, St. Joseph, St. John, Austrian Hospice, and the Red Crescent. Two further hospitals were almost ready to open by 1967: Makassed Hospital on the Mount of Olives, whose opening was delayed until 1968 and took place despite Israeli threats of confiscation; and the Jordanian Government Hospital in the suburb of Sheikh Jarrah, which was confiscated by Israel in 1967 and turned into Police Headquarters. Meanwhile, other major Palestinian towns such as Bethlehem, Hebron, and Nablus were also developing new government and/or NGO hospitals and medical centers.

As Israel started moving from a temporary military occupation to a long-term policy of annexation and colonization of WBG, it had to make long-term plans to administer the territories. From day one, while the declared policy was to adhere to the principles of international law and the Geneva Conventions with regards to occupied territories, the operative policy closely resembled Theodor Herzl’s “Blue Plan,” outlined in his secret diaries of 1895: to settle every inch of the “Promised Land” but “to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it employment in our country.” One such manifestation of this plan was Israel’s refusal to readmit 300,000 refugees who fled or were outside WBG (including East Jerusalem) during the 1967 war.

♦ Hospital bed to population ratio of 1.4/1,000 in the West Bank and 1.2/1,000 in the Gaza Strip in 1988–1989 continues to be very low and compares unfavorably with the Israeli average of 6.1/1,000 obtained in the late 1980s. (UNCTAD, 1994)

The policy of coercing as many Palestinians as possible to leave the OPT was soon put into practice in every sphere possible, although the sphere of health required careful consideration by the Israeli occupation authorities. The reasons for dealing positively with some aspects of health beyond the minimal approach that Israel had applied to all other sectors were broadly twofold: (a) a need for “self-protection” from epidemics and other communicable diseases, since viruses do not “stop at checkpoints” and (b) a need to utilize – at least for a certain period – the opportunity of a “cheap but healthy” workforce for carrying out menial jobs in Israel and the occupied territories (construction workers, waiters, cleaners, drivers, domestic workers, garbage collectors, etc.).

This is not to deny that there were many well-meaning, left-leaning Israeli health NGOs and professionals from within and outside the official Israeli health system who were interested in promoting the health of the Palestinian people in WBG due to deep political and/or humanitarian commitment. But often these individuals and organizations were looked upon by the official Israeli authorities as renegades or anti-establishmentarian.

This dual consideration of the official authorities – coercing people to leave while keeping those who remained adequately healthy – led to the development of the following practices by the Israeli “Civil” Administration health department:

- Ensuring adequate primary health care services, especially prevention of communicable diseases and comprehensive child immunization programs

- Neglecting non-communicable and hereditary diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and cardiac failure

- Failing to develop WBG hospital services, especially tertiary care, meaning that almost all complex surgical and medical cases were referred to Israeli hospitals, paid for by taxes and health insurance forcibly collected in the OPT

- Offering only minimal specialist training opportunities to Palestinian health professionals working in the “government” health department in the OPT, with the aim of ensuring diagnosis and follow up – rather than treatment – of complex/serious diseases

- Denying Palestinian CSOs and NGOs the opportunity to officially or “legally” work with the Palestinian population in OPT

- Limiting international support (“interference” as it was regularly referred to by Israeli authorities) to Palestinian health NGOs

While the first practice ensured that the “Residents of the Territories,” according to Israeli-government terminology, would remain sufficiently healthy and – more importantly – well-vaccinated so that they would not create epidemics that could also infect the Israeli Jewish population, the other five practices ensured that the Palestinian health system attained only minimal development, while the Israeli hospitals received the complex surgeries/medical cases. This meant that (a) Israeli hospitals were well reimbursed for their services from the OPT taxation system administered by an unsympathetic “Civil” Administration and (b) young Israeli specialists, medical residents, and students received solid and varied training when exposed to abundant numbers of complex/rare medical cases referred from the OPT.

David Stone, in his 2014 paper, further asserts that Israel provided “high quality training for doctors and nurses bringing modern standards to anesthesia, renal dialysis, cardiac surgery and many other critically important fields” and that an “ambitious hospital development program resulted in several new units… being built or existing hospitals being greatly enlarged.” Both claims are demonstrably untrue. Firstly, most of the Palestinian doctors who were chosen for training in Israeli hospitals in the 1980s and early 1990s (after a full security check of course) and were sent back to work in WBG “government-run” hospitals as “specialists,” received inadequate training (only two years instead of four to five years) and were never officially or fully certified by the Israel Medical Board as “specialists.” These Palestinians mainly acted as “assistants” to Israeli specialists, identifying and referring the medical cases and following up after treatment or surgery. Secondly, in 1994, when the Israeli “Civil” Administration handed over the health sector to the Palestinian Authority (PA), the hospitals in many towns (Jericho, Ramallah, Tulkarem, Nablus, etc.) were handed over in a run-down state, unfit for the safe treatment of patients, with neglected building infrastructure, unsanitary wards, archaic medical equipment, and inadequate medical and nursing staff.

♦ The insufficient health-system infrastructure, the high cost of hospitalization, antiquated diagnostic equipment, old buildings experiencing problems with electricity, heating, and laundry facilities, and a shortage of essential medical equipment, staff, and drugs remain serious obstacles to health protection.” (UN Commission on the Status of Women)iii

Contrary to Stone’s disingenuous claims, therefore, it was despite all the impediments created by Israeli occupation authorities that the Palestinian health system succeeded in growing between 1967 and 1994, and particularly after the eruption of the first Intifada (uprising) in 1987. Palestinian health NGOs mushroomed everywhere. In primary care, national groupings such as Medical Relief, Health Services, and Health Care Committees became very active and boasted several hundred medical centers and clinics all over WBG, despite Israeli obstacles. In secondary care, Patient’s Friends and Red Crescent societies opened advanced medical centers in every major city and town. In tertiary care, Makassed Hospital became the main referral center for complex/serious cases. Many of these community-based groups were supported either by the PLO and its leading political factions, the Palestine Red Crescent Society; international solidarity groups such as MAP, NORWAC, OXFAM, Save the Children, Médecins Sans Frontières; international agencies such as UNRWA, UNDP, UNICEF, UNFPA; Arab Gulf States such as Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, and Bahrain; or by Israeli human rights/anti-occupation activists.

♦ Those well-meaning Israeli health NGOs and professionals, who were genuinely interested in promoting the health of the Palestinian people in the West Bank and Gaza, were looked upon by the official Israeli authorities as anti-establishmentarian.

The main factor in improving the health status of the Palestinian people following 1967 was quite simply the dogged determination of the Palestinian people, together with the support of international organizations. Israel not only failed to carry out its responsibility as an occupying power but actively attempted to hinder progress.

Since 1994, and after handing over health – among other sectors – to the PA, the health status of the Palestinian people has improved further. Yet even today, the occupation authorities continue to hinder the full development of the sector in several ways:

- The closed borders with Jordan and the outside world hamper the importation of several advanced-technology machines, especially those using radioactive material, such as advanced PET, Gamma Camera, Gamma knife.

- Visa restrictions prevent highly qualified medical staff who do not hold a Palestinian ID from returning or even visiting for short periods to help develop the system and train medical staff.

- The closure of East Jerusalem, considered the Palestinian hub of tertiary medicine with its advanced hospitals and medical centers, and the restrictive “security” and licensing rules related to the closure, regularly denies patients and medical staff free access to these referral/training centers.i

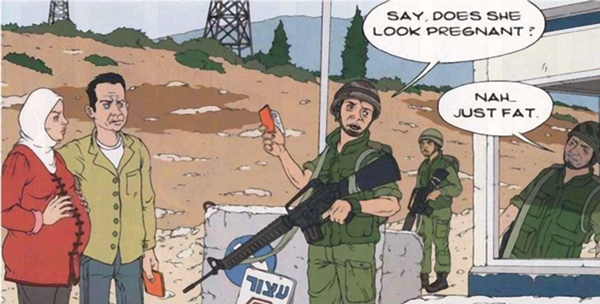

- The hundreds of Israeli checkpoints that are opened and closed on a whim, coupled with the back-to-back patient handover system for WBG-East Jerusalem ambulances, have caused the conditions of severely sick patients to deteriorate and led to numerous cases of mothers giving birth at the checkpoints.

- The strict closure of Gaza since 1993, and even more so since 2007, has drastically worsened the health situation there, increasing general morbidity and mortality among Gazans, especially with regards to infant and maternal mortality.

♦ Improvements in the Palestinian health sector are ultimately due to the determination and resilience of Palestinian society, together with the principled support of certain sections of the international community.

In conclusion, despite absurd claims to the contrary, there is firm evidence that the first 25 years of the occupation attempted – but failed – to severely hamper the development of an adequate and independent Palestinian health system. There is also no doubt that the second 25 years of the occupation, with the advent of the PA, allowed the Palestinian health system to develop further. While Palestinians should be proud of their steadfastness and everything they have achieved in the field of health, there is still a long way to go. The only way for the Palestinian health system to realize its potential and develop to its full capacity is by ending the occupation. And after 50 years, that moment cannot come soon enough.

» Dr. Rafiq Husseini has a PhD in medicinal chemistry and a master’s in health management. He is currently director of Makassed Hospital in East Jerusalem. Previously he worked as CEO of MAP-UK (1986–1993), director of the Palestine Council for Health in Jerusalem (1994–1995), director of operations at Welfare Association (1999–2005) and chief of staff at the Office of the Palestinian President (2005–2010). Dr. Husseini is co-editor of Separate and Cooperate, Cooperate and Separate: The Disengagement of the Palestinian Health Care System from Israel and Its Emergence as an Independent System, Westport, CT, Praeger, 2002.

i. See also the UN report “East Jerusalem: The Humanitarian Impact of the West Bank Barrier on Palestinian Communities,” Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, occupied territories, available at https://www.ochaopt.org/documents/jerusalem-30july2007.pdf.

ii. UNCTAD, Health Conditions and Services in the West Bank and Gaza Strip (UNCTAD/ECDC/SEU/3), study prepared by Dr. Rita Giacaman, UNCTAD consultant, 1994.

iii. UN Commission on the Status of Women, The Situation of Women and Children Living in the Occupied Arab Territories, 31st Session, February 24–March 5, 1986.