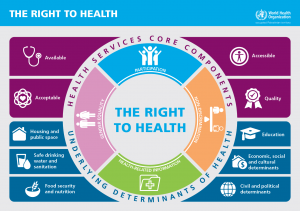

Health advocacy comprises a range of actions to raise health issues on the political agenda in order to promote change in policy and practice to benefit the health of populations. The right to health provides a cohesive vision for effective health advocacy that recognizes the political, legal, and practical avenues for realizing that vision. Figure 1 shows the core components of the right to health, which include accessible, available, acceptable, and high-quality health services, along with underlying determinants of health, such as access to safe drinking water and sanitation, food and nutrition, and shelter and education.*1 The right to health relates closely to other human rights, such as the right to life and the right to a life with dignity.

In addition to providing a cohesive vision, effective advocacy requires thorough analysis of barriers to achieving that vision. The ongoing occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip has presented significant obstacles to realizing the right to health for Palestinians.

Lack of territorial sovereignty has consequences for the income of the Palestinian Authority and hence for the sustainability of the Palestinian health sector, which is highly donor dependent. The Paris Protocol on Economic Relations formalizes an effective customs union with Israel and has implications for the affordability of medicines and overall health care. The Palestinian Ministry of Health overpays substantially for many medicines, compared to international benchmark prices, with import restrictions being a major contributing factor to increased prices.*2 Long-term depletion and shortages of essential medicines and supplies particularly affect Gaza, where 46 percent of essential medicines had on average less than a month’s supply remaining over the course of 2018.*3

In the Gaza Strip, 12 years of blockade have detrimentally affected the health sector. There has been a per capita reduction in health staff, especially with respect to medical specialists. The limited and unpredictable electricity supply to Gaza means that hospitals and clinics depend on the provision of fuel to supply emergency generators. Fuel shortages and electricity outages have the potential to put patient lives at risk. For example, when backup generators failed at the Pediatric Specialized Hospital in Gaza City, medical teams had to manually ventilate four children until maintenance engineers were able to repair the machinery. Fluctuations in energy supply and power failures also reduce the lifespan of sensitive hospital equipment.

Achieving the right to health in Palestine is hindered by obstacles that impede the provision of and access to health care as well as by circumstances that affect the underlying determinants of health.

The legislative and physical division of the West Bank presents obstacles to effective health care provision for vulnerable communities – such as those in Area C, which comprises more than 60 percent of the West Bank. Discriminatory planning policies restrict the development of permanent health facilities in this area, many of which rely on mobile clinics for primary health care. Over a third of Palestinians living in Area C have limited access to primary health care.

Attacks against health care also impact the delivery of effective care to patients. From March 30, 2018 to March 31, 2019, WHO recorded an unprecedented 521 attacks against health care in the West Bank and Gaza Strip; 446 of these attacks happened in Gaza in the context of the Great March of Return, resulting in 3 deaths and 731 injuries among health workers. In addition, 104 ambulances and 6 other forms of health transport were also damaged, as well as 5 health facilities and 1 hospital. In the West Bank, the 75 recorded attacks included the killing of a health worker in Dheisheh Refugee Camp and 30 incidents of physical attacks against health staff, ambulances, and health facilities.

A further barrier that impedes or prevents access to health care is the Israeli permit system. This is particularly severe for patients in the Gaza Strip, where movement in and out – through Erez terminal to reach the West Bank, Israel, or Jordan, as well as through Rafah terminal to Egypt – is heavily restricted by the ongoing blockade. Essential health services, including certain treatments for cancer patients, are not available in Gaza – meaning that patients must rely on access to health services in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, Israel, and elsewhere. In 2018, only 61 percent of patient applications for Israeli permits to exit Gaza were approved. This is a substantial decline from an approval rate of more than 90 percent in 2012.*4

Beyond the figures are human lives. Fatima, the mother of a three-year-old boy, was diagnosed with colon cancer in 2016. She needed to travel out of Gaza for essential care, including chemotherapy and biological therapy that were not available in Gaza at the time. Fatima received exit permits the first three times she applied, but nine subsequent applications for a permit to exit Gaza for health care were unsuccessful. Patients who face such severe barriers are left wondering why, and the permit system offers them no answers. Security concern is the generic reason given for denial of permit applications, but the vast majority of unsuccessful applications are simply delayed, with patients receiving no definitive response to their applications.

In the West Bank, access to health care is further hampered by the extensive and shifting system of Israeli checkpoints, and the settlement infrastructure and separation wall that divide the land and communities. From April 2018 to March 2019, WHO recorded 56 incidents of delaying or preventing the delivery of health care, including to 14 Palestinians whose wounds proved fatal.

Advocacy is everyone’s business. It’s up to all of us to make the right to health a reality for all.

Finally, barriers to the right to health are not restricted to obstacles to the provision of health services, they also affect the underlying factors that influence our health and well-being, and our chances of developing illnesses. The blockade on Gaza has had a damaging impact on its economy. The Gaza Strip was largely dependent on access to the labor market in Israel between 1967 and the late 1990s, with the percentage of the employed population working in Israel peaking at 45 percent between 1980 and 1987.v*5 In the second quarter of 2018, unemployment in Gaza was 54 percent; and the rates were higher among young people (over 70 percent) and among women (78 percent). Poverty reached 53 percent in the same year, while more than two-thirds of the population were food insecure.*6 Unemployment, poverty, and food insecurity are often associated with poor health.

Documentation and evidence collection are necessary for the effective engagement of legal avenues for advocacy, but legal advocacy alone is not enough to ensure the respect, protection, and fulfilment of the right to the highest attainable standard of health. Civic space to organize and engage in constructing and realizing a positive vision for our collective existence and all the aspects of our lives that impact our health is necessary for attaining the right to health. This links the right to health closely to those other human rights: the right to freedom of assembly, the right to freedom of association, and the right to freedom of speech. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Constitution of the World Health Organization provide us with a radical vision for a politics of equality and health for all. It’s up to all of us to realize that vision.

*1 Right to Health 2017, WHO oPt, available at http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/WHO_Right_to_health_Book_for_web.pdf?ua=1&ua=1.

*2 Public Expenditure Review of the Palestinian Authority: Towards Enhanced Public Finance Management and Improved Fiscal Sustainability, World Bank, 2016.

*3 Gaza’s Central Drug Store.

*4 WHO oPt, Right to Health 2017.

*5 Arnon, A., Israeli Policy towards the Occupied Palestinian Territories: The Economic Dimension, 1967−2007, Middle East Journal, Vol. 61, No. 4 (Autumn, 2007).

*6 2018-2020 Humanitarian Response Strategy, occupied Palestinian territory, OCHA, available at https://www.ochaopt.org/sites/default/files/humanitarian_response_plan_2019.pdf.