The concepts of intersectionality and veganism – seeing the interconnection between all forms of oppression and how the cycle of violence eventually reaches animals – are not widely recognized in Palestine or in many other places in the world, including Europe. Hierarchal violence, however, either amongst humans or against animals, can be witnessed in Palestine. In fact, the colonial legacy and the prolonged Israeli occupation have played a significant role in hindering the evolution of a progressive intersectional society in occupied Palestine, as it has remarkably been taking backward steps on women’s rights, LGBT rights, and animal rights. Therefore, going back to the roots is a step forward in spotting when and where things went wrong and how to get back on track to create a better atmosphere for humans and animals alike.

In Palestine, vegan food is most widely known as siyami, the Arabic term for food that falls within the regulations of the Christian fast, and it is the term I often use when inquiring about the ingredients in dishes at an open buffet or at a sweets store in such cities as Ramallah and Bethlehem. However, traditional Palestinian cuisine has been mainly vegetarian, even vegan to a large extent, but it has not been labeled as such. In the past, meat consumption was low in Palestine, as in many other places around the world. It is believed that the remarkable increase in meat consumption can be linked to a number of factors, including the dominant global capitalistic economy. Under the impact of Ottoman rule over Arabic culture, meat was introduced as an elite food − it was assumed that whoever had more money should automatically consume more meat. And finally, the Palestinian people have become increasingly disconnected from their land due to the ongoing forcible displacement and the high cost of investing in land cultivation, given that the natural resources in Area C − the more than 60 percent of the West Bank where most agricultural areas are located, including water resources − are in the hands of the Israeli occupation. It is worth highlighting that in the wake of the Nakba, The Catastrophe of 1948, Palestinians started to rely on purchased rather than homegrown or homemade food. The forced displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who became refugees scattered throughout Palestine and its neighboring countries prompted many to rely on aid, including food, provided by the United Nations (UN). It is also believed that canned meat and sardines were introduced as aid food after the Nakba.

Considering that Palestine is a relatively poor country, meat and dairy consumption nowadays is necessarily connected to purchasing power and not the result of a conscious choice. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), the current monthly meat and poultry consumption per capita is 3.7 kg. The PCBS statistics also state that dairy foods and eggs rank as the fourth most consumed food, with 2.3 kg per capita per month. In addition, the Union of Palestinian Farmers announced in August 2017 that 204 million liters of cow milk are being consumed every year in the occupied Palestinian territories. Given the aforementioned factors, the consumption of meat, dairy, and eggs would increase if the society becomes richer. This is actually being promoted and encouraged through international aid programs in Palestine, including those run by UN agencies.

Therefore, most Palestinians consider meat, especially red meat, to be a luxury food. It is mandatory to serve meat to one’s guests at home or in a restaurant since it is perceived as a way to show respect and generosity. At weddings, especially in the southern West Bank, serving lamb and beef in huge amounts is a must. The smallest wedding would cost at least ten lambs. In the same context, sacrificing animals (mainly lambs and cows) is still an annual religious ritual performed during the feast of Al-Adha, when many Muslim families slaughter one animal or more as a sacrifice to God and to feed the poor. Since slaughtering animals is often done in public, in the streets or in the backyards of family homes, most commonly in rural areas, children learn exactly where meat comes from and how it is obtained. In the same context, it is unusual to find vegan options as main courses on the menus of restaurants in Palestine, and it is very uncommon to find the vegan options of salads and sweets labeled as vegan. Consequently, the cultural and religious environments in Palestine, combined with the negative impact of the Israeli occupation on Palestinian life, keep veganism low on the list of priorities compared to other issues or causes such as land liberation and human rights.

From an intersectional perspective, however, highlighting the environmental damage caused by meat production, its negative impact on health, and the fact that it increases poverty worldwide could help promote veganism in Palestine and in the Arab world as a noble cause of great priority. Religious persons, for instance, should be made aware of the damaging impact of animal farming industries on the environment and of how consumption of animal products increases and deepens global poverty, as well as contributes to poor health that can result in heart disease and early death. Considering that the aforementioned arguments may be less important to many people in Palestine than in other countries, introducing veganism from the perspective of the oppressed might provide a different angle. As an oppressed people, we Palestinians may come to a greater understanding of this through going back to our roots and examining our Arabic cultural heritage. At various times throughout history, our society has certainly been more progressive than other countries in terms of human rights and animal rights.

To advocate for an intersectional Palestinian society is to reach a point where one would not consider veganism to be merely a diet restricted solely to plant consumption but rather a lifestyle that helps the vegan Palestinian person to fight against all acts of cruelty and exploitation and against all forms of oppression (since we have experienced it ourselves as oppressed people), where Palestinian feminists would see that consuming animal products is an expression of power that serves the hierarchal system that they want to end.

Keeping the Palestinian angle of the story in mind, it is also important for veganism advocacy in Palestine not to present this issue as yet another “Western idea” imposed on us. Firstly, simply because it is not. Secondly, because this level of awareness has been experienced by people throughout history. Although there may have been many who lived a vegan lifestyle, we only know about the well-known historical figures such as Epicurus, Socrates, and Buddha.

More interestingly, an historical Arabic figure who was vegan would have more impact on the society. And yes, we have Al-Ma’arri, an Arab philosopher who was born in 973 and who wrote a remarkable, 1000-year-old poem titled I No Longer Steal from Nature, in which he expressed outstanding compassion towards animals and where he strongly refused to exploit the mother-child relationship:

Do not unjustly eat fish the water has given up,

And do not desire as food the flesh of slaughtered animals,

Or the white milk of mothers who intended its pure draught

for their young, not noble ladies.

And do not grieve the unsuspecting birds by taking eggs;

for injustice is the worst of crimes.

And spare the honey which the bees get industriously

from the flowers of fragrant plants;

For they did not store it that it might belong to others,

Nor did they gather it for bounty and gifts.

I washed my hands of all this; and wish that I

Perceived my way before my hair went gray!

I also remember a story I was told during my school-age years. Once, blind Al-Ma’arri was seriously ill and the people who looked after him brought a cooked chicken to feed him, even though they knew he was vegan. They justified their action by saying that the doctor had prescribed chicken for a speedy recovery. Heartbroken, he touched the cooked chicken and uttered his famous statement (talking to the dead bird): “They only prescribed you because you are weak. Would they ever prescribe a lion cub?”

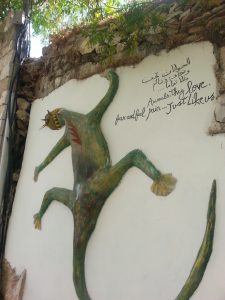

In fact, we do not have to start from scratch as long as we have the beautiful wall of artwork outside Battir Landscape Ecomuseum in Bethlehem’s Battir village, which was created in honor of a lizard killed by a person who was visiting the village.

In order to utilize the intersectionality of veganism and the political situation for advocacy work in Palestine, we need, on one hand, to clearly state that going vegan is in line with the humane morals that can be found in our Arabic literature, including the Qur’an, which states that all animals and birds are nations of their own, communities of their own, just like humans (6:38). Hence, it is important to assert that veganism and intersectionality are actually a significant element in the fight against the system that seeks to suppress these values. We also need to illustrate how colonialism has promoted women’s subordination to men and homophobia and how this has been manifested in the cultural norms and the religious beliefs until now. There is a simple example in the fact that Arab women historically did not change their surnames after marriage, and it is clearly documented that women started to acquire their husbands’ surnames during the colonial era and continued the practice afterwards. In addition, there is significant literature on homosexuality as a normal human sexual orientation in Arabic societies during the Islamic era. However, it could be argued that even in those days, homosexual men were still considered to be “un-men” (depending on their role in the physical relationship), but there is also evidence that they were at least recognized for their sexual identity (as can be seen in a drawing by Yahya Ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti, shown in the book Al-Maqamat [The Meetings], published by Al-Hariri in Syria or Iraq, c. 1240, in which he illustrated two main male figures kissing in a farewell scene). This recognition is indeed progressive compared to the situation today, where coming out as a homosexual is almost impossible in Palestine and other Arab and Islamic countries. On the other hand, it is important to underline how the Ottoman rule and the prolonged Israeli occupation have hugely contributed to remarkably emphasizing various forms of oppression that permeate a cycle of violence, which is a fundamental obstacle in Palestine’s efforts to develop into a broad-minded society that acknowledges that all oppressive institutions (racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, xenophobia, classism, and speciesism) are interconnected and cannot be examined separately.

*Orlando Shootings: It’s different now, but Muslims have a long history of accepting homosexuality, Scroll.in, April 2019, available at https://scroll.in/article/810093/orlando-shooting-its-different-now-but-muslims-have-a-long-history-of-accepting-homosexuality.