My research into Palestine’s history reveals the existence of a seemingly parallel universe in London.

At events related to archaeology in Palestine – which are plenty, owing to the work of institutions such as the Palestine Exploration Fund, the British Museum, and University College of London’s Institute of Archaeology – I often find myself to be the only Arab among vast crowds of British people.

An even more compelling observation exists in academia. Anyone with an interest in Palestine’s archaeology and ancient history has probably noted the overwhelming superiority of the Western, Orientalist, Biblical perspective on Palestine, which inherently favors the “Israelite” or “Hebrew” part of history.

When I first began my research using “Gaza” as a keyword, I was unable to find anything remarkable – until I came across a major publication about “Ghuzze,” which, as it turns out, is the preferred name for Gaza among the many Orientalist and Biblical archaeologists who have conducted digs in the environs of Gaza. Many of the discoveries that were made by these archaeologists were chance discoveries as they were on a search for one particular site: Samson’s hill.

The story of “Samson the Mighty,” or Shamshoon al-Jabbar, is so well-known among people in Gaza that it was one of the first fables I remember hearing as a child. Despite the fact that Samson was an Israelite figure who had killed thousands of Philistines in Gaza, the story portrays him as a mighty hero, a symbol of bravery and courage, and portrays Dalilah as a smart but ultimately flawed woman. The story has also enchanted the Western imagination for centuries: at least three Hollywood movies, two musicals, countless paintings, and many novels have been inspired by the story, focusing on the Israelite hero who fell in love with Dalilah, who deceived him and betrayed his love.

There are two versions of Samson and Dalilah’s story: the Biblical story (Judges 16: 4ff) and the local Gazan fable. Both versions describe Samson as an Israelite man of great strength who was sent by God to defeat the Philistines, enemies of the Israelites, who lived on the coast (including Gaza). According to the Bible, Samson had spent the night with a harlot in Gaza when he managed to escape from the locals who wanted to kill him by tearing down the city gates that he then carried off to a hill in the direction towards Hebron. Shortly after, he fell in love with another Philistine girl, called Dalilah, who lived in a nearby valley. According to local Gazan lore, Samson met Dalilah while sneaking into Gaza to destroy its temple. In the Biblical version, Samson fell in love with Dalilah who was then bribed by local rulers to make him share the secret of his strength, whereas the local fable states that Dalilah intentionally seduced him to find out his secret. Thus, while both versions agree that Dalilah convinced Samson to share his secret, the Bible describes this act as deceitful, whereas the local fable describes it as heroic. In both versions, the Philistine rulers of the city captured and enslaved Samson and cut his hair in public, thus depriving him of his strength. Both versions also agree that one day, while the Philistines were making sacrifices to their gods at the Temple of Dagon to celebrate Samson’s capture, Samson, whose hair had re-grown, destroyed the temple while shouting “Let me die with the Philistines!” killing himself and the all the Philistines who were gathered at the temple.

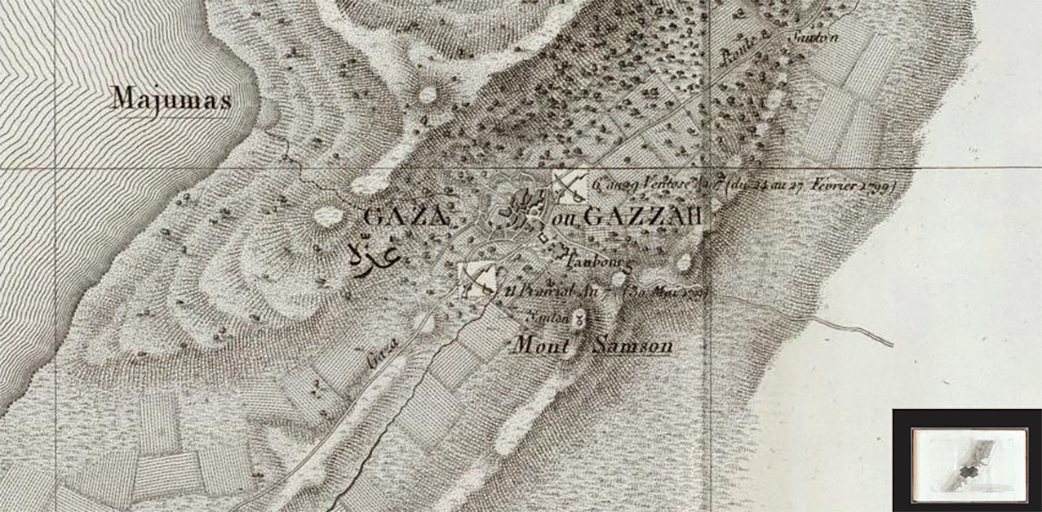

A number of travellers and scholars have tried to assign locations to the places where Samson is said to have carried the gates of Gaza after his nightly escape from the city, where he died between the pillars of the temple he brought down when his hair had grown back, and where he was buried. Pierre Jacotin in 1829 published a map on which he inscribed Mt. Samson at a location to the south of old Gaza city. As early as 1850, an Irish reverend named Jesse Spencer visited Gaza and noted that there is a hill called “Sampson’s Mount.” William McClure Thomson, after travelling the Holy Land, wrote in 1878: “There are now neither walls nor forts, but the places of certain gates belonging to ancient walls are pointed out. The only one that interests me is that which bears the name of Samson, from the tradition that it was from that place that he carried off the gate, bar and all.” Other travellers who visited Palestine in the eighteenth century believed that they had visited Samson’s tomb but gave no further details as to its location (Mary Herbert in 1867 and Emily Hornby in 1899).

The geographic reference in the Bible that attests to Samson carrying off the gates he had pulled down to “a hill before Hebron” points to a place on the eastern side of the mound that indicates the location of Gaza’s old city, the famous Tell al-Muntar. But no remains of gates or a temple from the Philistine era have been found there. Nevertheless, the location indicated on Jacotin’s map led Western travellers to come to Gaza in order to visit the hill that could be interpreted to indicate the place where Samson had carried the gates, where the Philistine temple had stood that he caused to collapse, or where he was buried. This attention might even have led the locals, Muslims and Christians alike, to believe that the story (be it in its Biblical or folkloric version) had indeed happened in the place where the travellers had claimed.

Alternately and interestingly, however, there exists a tomb in the old city of Gaza which locals believe to be Samson’s tomb, but in fact, it is a shrine of a ninth-century Muslim saint called Sheikh Abu Al-Azm – which in Arabic means “the mighty,” hence the connection to al-Jabbar (Shamshoon). While the details of how the tomb came to be known as Samson’s tomb are unknown, some locals even claim that Sheikh Abu Al-Azm is indeed Samson himself.

Although the story of Shamshoon is regarded as a legend of heroism among many Palestinians, it is less known that in 1948, the Israeli army created a special brigade called “Shualei Shimshon,” Samson’s Foxes, to attack and destroy Gaza and its vicinity. And it is equally little-known that in 2002 this unit was revived as a covert brigade whose soldiers sneaked into Gaza to assassinate their targets. The name “foxes” is derived from the Biblical story in which Samson attached torches to the tails of foxes and made them run through Philistine fields (the tactic is carried out in slightly different ways today).

♦ There exists in Gazan lore an alternate version of the famous story of Samson and Dalilah. In this legend, the Biblical hero is an Israelite villain and the Philistine girl Dalilah is the heroine.

Yet, independently of (or even despite) a distorted history and Orientalist influences on local lore, the Gazan legend of Samson the Mighty perseveres. In the year 1970, the renowned late Gazan poet Muin Bseiso wrote a play inspired by Samson’s story, taking pride in Dalilah, “the Gazan girl” who defeated Samson the Israelite. Bseiso criticized the general lack of knowledge regarding the details of the original story, both among local people and Westerners alike. Slating locals who had turned Samson into a hero without realizing that he had killed their ancestors, Bseiso in his script glorifies Dalilah rather than Samson, whom he depicts as a strong man without wisdom. Bseiso’s script ends with a phrase that could not be more relevant to our situation today:

“Old Gaza is telling today’s Gaza, which is resisting the Israeli Shamshon, that tyranny is doomed to be tied to the mill, to turn around the stone forever. Tyranny will destroy itself.”

» Yasmeen Elkhoudary is a researcher on Gaza’s history and archaeology, and an associate fellow at the Centre for Palestine Studies – SOAS. As a Palestinian based in London, she is currently writing a book about Gaza during the British Mandate to mark the centenary of the Balfour Declaration. She publishes a blog at yelkhoudary.blogspot.com.

i Pierre Jacotin, “Gaza,” David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, available at http://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~25534~1030032:43-Gaza-?qvq=w4s:/who%2FJacotin%25252C%2BPierre%25252C%2B1765-1827%2Fwhat%2FAtlas%2BMap%2Fwhen%2F1826%2F;lc:RUMSEY~8~1&mi=45&trs=50.

ii Jesse A. Spencer, The East: Sketches of Travels, Egypt and the Holy Land, John Murray, London, 1850.

iii William M. Thomson, The Land and the Book: Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery of the Holy Land, T. Nelson and Sons, London, 1878. Incidentally, Thomson, who spent many years living in Beirut, recommended in 1866 that a college be established. This institution evolved to become the American University of Beirut.