Featuring a unique and charming landscape, deep in history as well as on Earth, the Jordan Valley runs along the Jordan River that is, in fact, a holy river. Its water comes from three tributaries: the Liddan (Dan) in the north, Hasbani from Lebanon, and Banias from the occupied Golan Heights that meet to form the Upper Jordan River. It runs through what used to be Hula Lake but, sadly, has been drained, and then discharges into the Sea of Galilee, also known as Lake Tiberias. South of the lake, the Yarmouk (as well as a few smaller tributaries) joins it, forming the Lower Jordan River that extends some 150 kilometers, meandering its way through the distinctive features of the valley until it reaches the Dead Sea at the lowest point on Earth. This unique body of water, the richest in minerals and saltiest lake on Earth, contains potash, magnesium, manganese, iodine, bromine, and other minerals and salts. The entire above-mentioned natural system used to function as a balanced ecosystem before it was completely changed following the creation of Israel.

Throughout history, successive rulers have exposed the valley to transformations and alteration that have affected not only its geography but also its ecosystem. Western powers at the beginning of the twentieth century took measures to ensure their influence in mandated Palestine. In 1916, in the midst of World War I, Britain and France, with approval from the Russian Empire and Italy, outlined their future spheres of influence in the region, to be implemented at the end of the Ottoman Empire. In 1917, the British government promised Jews “a national homeland” in Palestine in efforts to gain support for the ongoing war. The British Mandate took over in 1923 – according to the plans outlined in the Sykes-Picot Agreement – and ruled Palestine until May 1948. Violence erupted in the Arab uprising of 1933–1939 between the local residents and the British occupiers who were facilitating Jewish migration to Palestine. Palestinians protested that the British were not only changing Palestine’s demography but also proposing to partition the land into an Arab and a Jewish state with an international regime in Jerusalem. In 1947, the United Nations adopted a partition plan that proposed an almost equal splitting of the land between Arab and Jews, but it was rejected by the Palestinians who saw no reason why they should surrender their land. Clashes erupted when in 1948 Israel declared a state, and a war erupted between poorly prepared Arab states and armed Zionist groups. It ended with Zionists controlling the entire territory proposed for a Jewish state by the partition plan, in addition to 60 percent of the land proposed as a Palestinian state. At this point, Israel controlled the Upper Jordan River, whereas the Lower Jordan River and the West Bank were under Jordanian control.

To enable the fulfillment of the Balfour declaration, hydrological survey missions had been carried out during the British Mandate era to explore Palestine’s natural resources and enable the creation and viability of the planned Jewish state. These studies came to conclusions and issued recommendations that included diverting the Jordan River and transferring its water to the Negev to alleviate the water shortage that is due to its desert climate. When the new state was about to be established in 1948, the founder of Israel, David Ben Gurion, introduced his vison of “making the desert bloom,” defining food security as the utmost priority for survival.

Thus, having taken control of the Upper Jordan River basin in 1948, Israel in 1952 embarked on the implementation of a seven-year plan that focused on irrigation and exploited the natural resources by transferring the waters of the Jordan River from Lake Tiberias to the Negev, draining Hula Lake, and “making the desert bloom.” The river’s diversion was completed in 1964, triggering military clashes between Jordan, Syria, Egypt, and Israel. On January 1, 1965, the Palestinian Freedom Movement Fatah announced its birth by launching attacks on the Israeli diversion structure and water pumps at Eilabun tunnel. Clashes between Arab states and Israel continued, escalating in the 1967 War in which Israel occupied the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip, the Sinai, and the Golan Heights, including the land called Shebaa Farms at the Lebanese border.

The past informs the present: Both the 1967 Allon Plan (named after the Israeli minister who drafted it shortly after the war) and American president Trump’s 2020 Peace to Prosperity Plan, also known as the Deal of the Century, aim to bring the Jordan Valley and other areas of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, under sole Israeli control – in violation of international law.

With these territorial gains, Israel controlled the entire length of the Jordan River, including many of the tributaries and the Dead Sea. The international community, however, did not recognize the legitimacy of the occupation and called for Israel’s immediate withdrawal from the occupied territories (UN Security Council Resolution 242), reaffirming its position in 1973 (UNSCR 338).

As the Palestinian territories in the West Bank and Gaza Strip are under Israeli occupation, the Fourth Treaty of the Geneva Conventions is applicable. Yet, contrary to its obligations under these conventions, Israel has utilized its control of the occupied people’s water and natural resources for its own population while hindering Palestinian access and use.

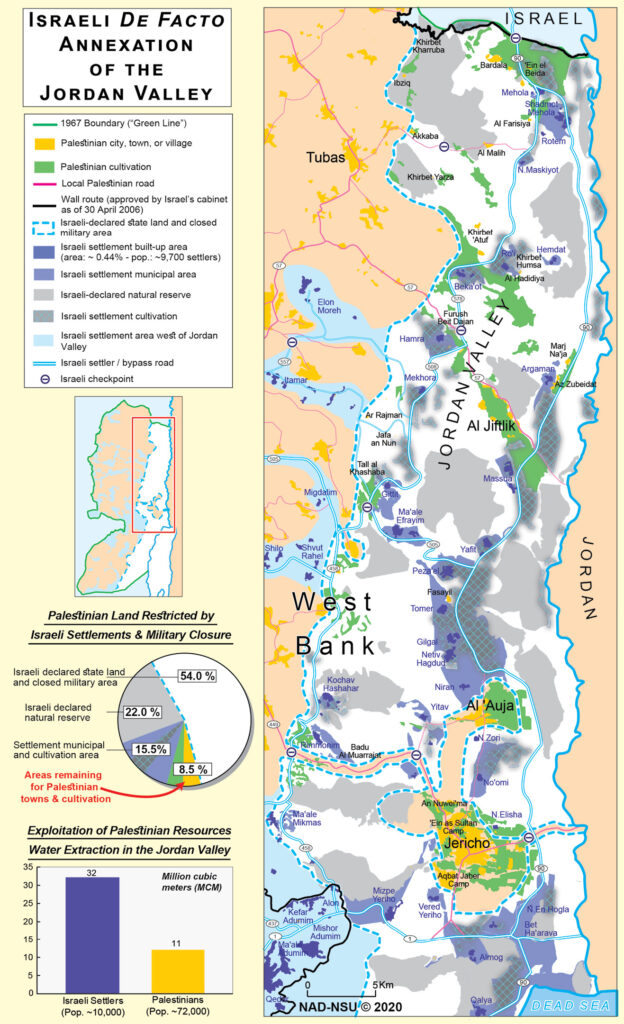

Days after its occupation of Palestinian territories in 1967, Israel issued various military orders that declared water a property of the state, conditioning any development or use of the water resources on the approval of the army’s water officer. Installation and pumps that existed along the Jordan River (150 pumps) were destroyed and the area along the river declared a military zone. Palestinian lands in the military zone have been confiscated, and Palestinians living there have been expelled from their lands. The remaining Palestinian population in the Jordan Valley amounts to 72,000 persons (including 21,000 residents of Jericho and another 15,000 in Ain as-Sultan and Aqabat Jabar refugee camps, and 15,000 who live in Auja, Nuimeh, Eldyook, Fasayel, Jeftlik , Elzbidat, Marj Naja and Marj Gazal villages); around 6,000 live in Aqaba, Kardal, Bardala, and Ein Byda; and 2,000 live in Aqrabanyeh and Nasatyeh – not including the Bedouin communities that make up another 13,000 persons. This means that, while making up 28 percent of the West Bank, the Jordan Valley area houses a mere 2.5 percent of the population, even though it is considered the breadbasket of the occupied territories.

Israel has concentrated its planning and strategies on security, settlement building and expansion, and state building, focusing on the exploitation of the occupied land and delinking itself from its responsibility towards the occupied people. The first and most informative plan that explains Israel’s strategy was put forward as the Allon Plan, designed in 1967. Immediately following the occupation of the West Bank, the plan envisaged surrounding the Jordan Valley with two lines of settlements, one extending north along the eastern slopes of the West Bank hill ridge, the other one extending all the way to the Dead Sea from East Jerusalem, including the Etzion bloc on the western border of the valley.

The Allon Plan includes security and demographic dimensions that are based on Israel’s belief that sovereignty over a large part of West Bank is a must for security and defense reasons, defining the Jordan Valley as strategic in this regard. Meanwhile, to prevent Palestinians who live in the Jordan Valley from becoming Israeli citizens, thereby changing the state’s demographical nature and identity, policies and restrictions were recommended to minimize Palestinian presence in the valley. Thus, Israel hoped to evade its obligations as an occupying power as outlined in the Geneva Conventions that stipulate allowing for autonomous governance. In 1968, Allon abandoned the option for Palestinian autonomous governance and instead adapted his plan by adding a corridor between the future West Bank and Jordan through the Jericho area, proposing in his final vision that the Jordan Valley remain in Israeli hands along with part of the Hebron foothills and East Jerusalem. All the remaining areas Allan proposed to hand back to Jordan!

The past informs the present: Both the 1967 Allon Plan (named after the Israeli minister who drafted it shortly after the war) and American president Trump’s 2020 Peace to Prosperity Plan, also known as the Deal of the Century, aim to bring the Jordan Valley and other areas of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, under sole Israeli control – in violation of international law.

Since 1967, the Palestinians who live in the West Bank have been deprived of their water and other natural resources. In the Jordan Valley, Israel started its settlement construction in two parallel sets of colonies: one set along the river and the second set on the eastern hills of the valley, as envisioned by the Allon Plan. Policies of restriction on access and movement in the Jordan Valley have been applied. Palestinians in the valley were expelled from the security zone established along the river and deprived of water; agricultural lands have suffered from water shortage, farmers and businesses have suffered from strictly imposed security measures and the lack of access and potential for marketing. In time, the Palestinian side of the Jordan River became deserted, and natural resources were restricted to the use of settlers and their agro-business development while Israel, the occupying power, contrary to its obligation under the Geneva Conventions, continues to exploit Palestinian lands and their natural resources, including through roads designed solely for settlers and Israeli citizens along the valley, such as Road 90.

Since the signing of the Oslo Interim Agreement in 1993, Israel has maintained its control of all water and natural resources of the West Bank. The West Bank is divided into three areas of jurisdiction. Area C represents 60 percent (which includes settlements and 90 percent of the Jordan Valley) and was put under Israel’s jurisdiction. The issue of water rights (including access to the Jordan River and the Dead Sea, in addition to groundwater and springs) has remained reserved for permanent-status negotiations. Hence, well-drilling or rehabilitation in the West Bank is not permitted unless approved by Israel.

Any Palestinian development in the water sector (water infrastructure, networks, and facilities for water treatment) must obtain the approval of the established Joint Water Committee (JWC). Likewise, any development or construction in Area C must obtain a construction permit from the Israeli civil administration. Israel’s military orders have established the de facto annexation of Palestinian land, water, and natural resources, and this situation has been arranged and maintained through the Oslo Interim Agreement!

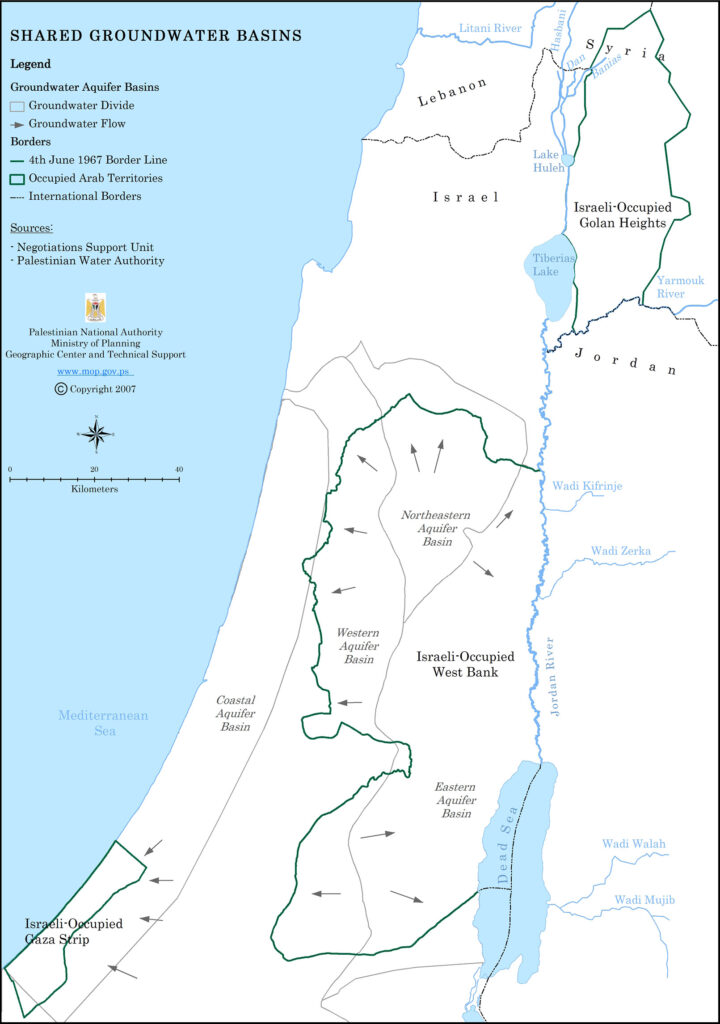

Article 40 of the Oslo Accords defined precise allowances of water from the West Bank’s three aquifer basins to Palestinians and Israelis. It allocated control of infrastructure development, including wells and springs, to Israel and provided to Palestinians no more than the right to use up to 118 million cubic meters (mcm), which represents merely 15 percent of the water in these aquifers. Israel, even though it possesses many other endogenous groundwater aquifers, including the water of the Jordan River, has been allocated 85 percent of these aquifer basins, a distribution considered deeply inequitable and unreasonable.*

In the Jordan Valley, Israel uses around 32 mcm out of what they extracted (a total of 46 mcm, in excess of the 40 mcm allocated by Article 40 of the Oslo Agreement) from the Eastern Aquifer located underneath the valley. This quantity is made available to the approximately 11,000 settlers in the valley, e.g., a settler receives around 8,000 liters per day. The inhabitants of the entire West Bank, however, more than 3 million Palestinians, have been allocated by the Oslo Interim Agreement a mere 118 mcm from all three aquifers combined! The average water per capita amounts to 108 liters per day for all Palestinian users.

In light of the potential annexation, Palestinians have been determined to leave the Oslo Agreements behind. Annexation will end the story of the two-state solution and kill any possibility for the creation of a sovereign, independent, viable future Palestinian state based on just and agreed-upon solutions for all issues of the conflict. A future Palestinian state, as proposed with all the conditions placed on the prospects of peace and prosperity, is a DEAD STATE if it lacks access to water, the Jordan River, the Dead Sea, or the Jordan Valley. Under annexation, all of this will be gone.

Through the annexation, Palestinians will lose not only their riparian, rightful water share (215–250 mcm from Lake Tiberias and the river itself) but also their riparian status in the basin as a whole! Including riparian rights in the Dead Sea. Losing the Jordan Valley means losing the place and space for the future Palestinian state. It means losing its food basket and reduces the ability of Palestinians to provide for their food security. Losing land, river, and sea will hinder any future development and the potential for industrial and economic prosperity. Annexation undermines and kills any possibility of comprehensive planning, eliminates the ability to absorb and resettle returnees, and prevents the meeting of future demands on water and food. Needless to mention is also the loss of 42 mcm of water currently used by settlers, until now believed to be regained under an agreement that dismantles the settlement under a mutually agreed-upon peace solution! It also kills any hope to exploit the 100 mcm of brackish water that discharges from the Fashkha Springs group near the Dead Sea. Annexation will place further pressure on natural resources, as we can expect that the increased demand of annexed settlements and their so-called natural growth and expansion will trigger the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians who will be forced to live in enclaves. All in all, annexation presents a threat to regional stability, in particular for Jordan, which will face future plans for either the resettlement of Palestinians who remained outside of Israel or for affiliating the remaining cantons, including the Palestinians living in them, with Jordan rather than with Ramallah, Nablus, Tubas, Jenin, and Jericho.

In the 27 years since the signing of the Oslo Agreements, Palestinians have had to make do with the lowest allocation of water per capita in the region, and their water in Gaza is not considered fit for human consumption. Palestinians have to purchase their water to face the increasing demand in light of the water shortage and the associated crisis looming in the oPt.

The fate of the existing, developed infrastructure facilities of Palestinians – including water wells, trunk lines, water networks, reservoirs, and more, almost all of which have been built through international financial assistance – is uncertain; most probably they will be confiscated. Mekerot, the national Israeli water company, will be replacing the West Bank Water Department in providing services, the price of water will no longer be subsidized, as is the case today, and agricultural development will suffer until it is minimized to the maximum. The conditions and status of import and export between the Palestinian local market and the “de jure annexed valley” will be an issue to consider as well.

Once upon a time, Palestinians in the Holy Land remained confident in the validity of international law and the Fourth Geneva Convention; they trusted the international community’s commitment to creating a future Palestinian state. Since 1967, despite hundreds of UN Security Council and General Assembly resolutions related to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, none of them has been implemented. Twenty-seven years of the so-called peace process, introduced by the Oslo Agreements, have led the Palestinians to a situation where instead of being able to establish a viable, sovereign, independent state, they must now face a fate without access to the Jordan River or the Dead Sea, with neither water nor land nor the possibility to grow food in the valley, but only the de jure reality of annexation and a proposal for a dead state!

*See for example, “Troubled Waters: Palestinians denied fair access to water,” Amnesty International, 2009, available at https://www.amnestyusa.org/pdf/mde150272009en.pdf, and Sheren Khalel, “Israel’s water cuts: West Bank ‘in full crisis mode,’” Aljazeera, June 23, 2016, available at https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/06/israel-water-cuts-west-bank-full-crisis-mode-160620133005799.html.