The Lord said to Abraham, “Go from your country, your people and your father’s household to the land I will show you.” (Genesis 12:1) It was by faith that Abraham, the Father of Nations, obeyed when God called him to leave his home and go to another land. He was the first recorded pilgrim of the three monotheistic religions. This recorded, historical event was the beginning of pilgrimage to the Holy Land, Al Bilad al-Muqadaseh. In fact, the three central figures of the three monotheistic religions were pilgrims themselves: Moses left Egypt and headed to the Promised Land, Jesus used to travel on pilgrimage to Jerusalem from his home in Galilee, and Muhammad’s mystical experience with the Night Journey to Jerusalem, Beit al-Makdes, was a spiritual pilgrimage. If we look at the origin of the Semitic word quds, we find Q-D-Š, a term that means “set apart.” Over the years, our Palestinian destination has really been set apart as a unique and unparalleled focus for the three Abrahamic faiths.

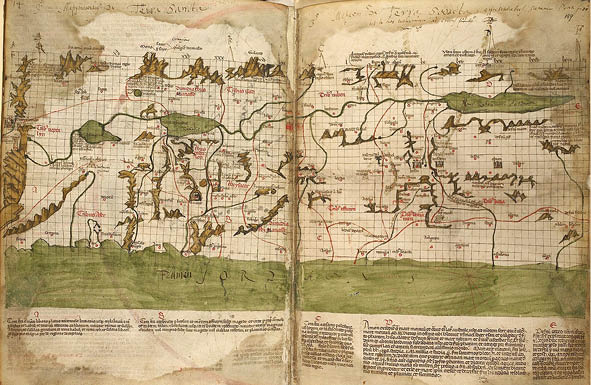

With these movements of four central figures in our three monotheistic faiths, a sacred geography was established that celebrates events that give deep meaning to the lives of millions of people worldwide and that have transformed world history in the process. Several sacred routes have been established over the millennia, and pilgrims have followed them through the ages. This sacred geography covers a wide area and encompasses several modern nation-states in our region. But the sacred routes are not only particular to our region. As Saint Paul spread Christianity throughout the Roman Empire, sacred routes connect numerous countries within Europe and with Palestine, the heart of the Holy Land.

Pilgrimages, devotional journeys, religious tourism, or faith-based tourism are all inspired by the same spiritual need: the search for a direct, tangible relationship with visible expressions of the sacred. Since time immemorial, such a quest has been popular. Herodotus (fifth century BC) was the first to record pilgrimages in antiquity. In his The Histories, he described Egyptian pilgrims who in their thousands traveled up the Nile to the temple in Memphis. In historical Palestine, even before Abraham’s journey, more than 20 sites had been dedicated to Canaanite fertility worship. These sites have been transformed over the years into what is now dedicated to Al-Khader (literally, the Green, known also as Saint George), venerated by the three Abrahamic religions and visited by people on Al-Khader Day or whenever a person may wish to pray to seek the intercession of Al-Khader to heal or bless someone. Palestine, moreover, holds the sites where the early prophets walked, the Holy Family originated, and Christ himself lived and preached, as well as the site of Prophet Muhammad’s Night Journey, in addition to sacred sites and shrines (maqam, mazar) that were established over the years, dotting the Palestinian landscape and reinforcing the concept of a sacred land. These maqamat and mazarat tend to be the places where especially revered figures of religious stature – Christian saints, Muslim scholars, the companions and followers of the Prophet of Islam – passed through or were buried. Frequently due to Biblical narratives, some of the shrines that are dedicated to prophets can be holy to the adherents of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim faiths.

The Palestinian tourism industry provides opportunities to share the very rich Palestinian culture and heritage of this special land with its guest pilgrims.

These sites include, for example, Maqam al-Nabi Musa in the Jordan Valley; the shrine of Rabiah al-Adawiyyah, the Sufi mystic, on the Mount of Olives; Rachel’s Tomb on the way to Bethlehem; Joseph’s grave on the outskirts of Nablus; and Abraham’s grave in the great mosque in Hebron. Many of these sites attract crowds, hold regional significance, and have been integrated into religious, social, and cultural practices that revolve around seasonal pilgrimage known as ziyyara (visit) or mawsim (season), and in certain instances can even have nationalistic significance. The seasonal celebration at Nabi Musa was a uniquely Palestinian cultural celebration, not based on the Islamic calendar but rather on that of the Christian community. Because of its strong cultural component, this eid was celebrated by Muslim and Christian adherents. Pope John Paul II, during the great Jubilee 2000, said that holy places are like memorials of salvation.

An important part of the Palestinian ethos is the issue of hospitality that has been held in high esteem throughout the ages. Its roots reach back to old Biblical traditions and are very important for all three monotheistic faiths. From the 76 Biblical verses that refer to hospitality and can be found in the Old and New Testaments, I will cite only a very few.

– Hebrews 13:2 “Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers, for by so doing some people have shown hospitality to angels without

knowing it.”

– 1 Peter 4:9–10 “Offer hospitality to one another without grumbling. Each of you should use whatever gift you have received to serve others, as faithful stewards of God’s grace in its various forms.”

– Matthew 25:40 “Truly, I say to you, as you did to one of the least of my brethren, you did to me.”

Islam also is very clear about the sacred importance of hospitality.

– “Let him who believes in Allah and in the Last Day be generous to his neighbor, and let him who believes in Allah and the Last Day be generous to his guest.” Forty Hadith an-Nawawi 15.

– Another Hadith from Al-Bukhari, according to Abu Hurairah, relates how Prophet Muhammad, when visited by a stranger who came to seek advice, made sure the guest would be fed. When there was not enough food, he asked his companions to share their meal and instructed his wife to send the children to bed hungry. The next day, when the companion who had shared his supper with the stranger came to find the Prophet, the latter said to him, “This night, God smiled.”

Palestine upholds the spirit of the People of Faith, and we welcome our groups as People of Faith, of whatever denomination, in the spirit of the Sufis – the mystical branch of Islam. The Sufis insist that when one has encountered God, one is neither a Jew, a Christian, or a Muslim. One is at home equally in a synagogue, church, or mosque because all rightly guided religion comes from God. Once one has come in touch with the divine, manmade distinctions are left behind.

I would like to try to highlight the mindsets of the people who relayed and then wrote the Old Testament and later, the New Testament. The authors of the Old and New Testaments were very much part of the Near East and shared the Near Eastern mentality. The early oral transmitters of the Biblical text would express the Biblical events and scriptures in poetic terms because it is easier to commit to memory in this manner. Poetic license can be expected. Often enough, they expressed themselves metaphorically. In other words, what was written was not always what was meant. The Old Testament writers and Christ himself expressed themselves in parables, allegories, and proverbs, drawing images from the land and its culture. Consider this famous passage:

“Truly I tell you, if you have faith as small as a mustard seed, you can say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move. Nothing will be impossible for you.” (Matthew 17:21)

When Christ said this, he and his disciples were at Beit Faji, Bethpage, on the Mount of Olives. He did not have to explain himself further, for a southward turn of the head brought Herodium into view, where the will of a man had literally moved a mountain: Herod the Great had the mountain next to Herodium leveled and used its earth to build up Herodium.

Cyril of Jerusalem, in the fourth century, called the land the Fifth Gospel. The early church fathers clearly understood that the scriptures could best be understood in the context of the land. The land in question is Palestine, and I shall claim that the continuity of Biblical culture still lies within Palestinian Bedouin culture and Palestinian village culture. So, for me, it is more comprehensive to read the scriptures in the context of my history, geography, and cultural heritage, including the use of metaphors in the Bible based on the landscape and agriculture which remain almost the same in the very hilly areas of the Palestinian villages. It seems clear that Christ and the prophets generally addressed the average people of their day. They needed no philosophy or deep exegesis, nor did they have to explain themselves. The meaning of their parables was clear to their audiences. The average person who heard their teachings and statements remembered them very well and maintained that rich oral tradition over generations before it was finally written down.

It is becoming very clear for us in Palestine – the heart of the Holy Land – and for many observers who are examining the challenges that face our country, that the economic future of Palestine depends on services led by the tourism sector, which is heavily dependent on faith-based tourism. In our third millennium, pilgrimages and faith-based tourism appear to have increased enormously. They are effecting political change through sustainable religious tourism that no longer involves only the faithful but also local, national, and international political and economic forces. Faith-based tourism is becoming a buzzword within the tourism industry worldwide, and thus within the national governmental and international organizations, as they incorporate this tourism sector into their strategic, socio-cultural, economic, and developmental plans. However, one must be cognizant of the fact that uncontrolled tourism development does not necessarily maximize its benefits to the Palestinian economy, social development, or other direct or indirect aspects. Palestinians cannot simply sit back and watch tourists who come to view nothing but the holy sites in Bethlehem, staying in the area for just a few hours, but spending their nights in Israel. This practice comes with negligible economic benefits and perhaps causes an even greater cost to the local community that has to maintain access, supply these visitors with facilities, and then clean up after them. Neither is it desirable to see secular tourists overwhelm the religious ones, where one can notice a lack of understanding of the original meaning of these religious sites and where no respect is given to them and their associated religious and cultural values – as is happening in some other parts of the world. Such phenomena can definitely give rise to a conflict between secular and religious tourists. (In Bethlehem this can be seen clearly when the cruise ship travelers arrive in large numbers that overwhelm the sites and their carrying capacity, which contributes to long lines at the main sites and causes deep frustration within the ranks of religious and secular tourists alike, as well as between the tourists and their hosts.)

Quoting John 1:38–39: “Jesus turned and saw them following. ‘What do you want?’ he asked. They said to him, ‘Teacher, where are you staying?’ ‘Come and see,’ he replied; so they went and saw where he was staying and spent the day with him.” The Palestinian tourism industry invites people of faith from the four corners of the world to “Come and see!”

Greater direct contact with peoples, places, and landscapes, if connected wisely to Palestinian cultural tourism, achieves a triple objective. It cements the local community’s feeling of identity, boosts participation in and support for tourism development and initiatives among the local community, and uses the identity of the local community as an asset and an additional attraction factor. Physical proximity and interaction and shared participation in local events and culinary experiences has numerous outcomes. Religious tourists acquire a deeper understanding of their own religious traditions, meanings, and certain cultural values that are transmitted through the local people through their traditions that originate from Biblical times, while the consumption of local products can be transformed into authentic experiences. The local host community gains experience from the cultural exchange itself, while benefiting economically from contributions to local household incomes through the sale of local food and products. At the same time, their business helps locals maintain and develop traditional crafts and foods and gives them further knowledge and pride in their identity and cultural distinctiveness.

The Palestinian tourism offer has tangible and intangible economic effects. Examples of the latter are an enhanced physical infrastructure and better cooperation between the various service providers, the local and national government agencies, and the private and public sectors, as well as the contribution to an enhanced image abroad. These intangible effects will further positively impact economic performance and increase the associated socio-economic benefits over the long term. The tangible effects such as increased sales, employment, and incomes contribute to the national wealth.

To market the Palestinian tourism product, splashy and expensive marketing campaigns that supposedly reward those who speak most polemically and with the loudest voices are unnecessary. Remember our Arab proverb that says, “The drum makes a loud sound because it is hollow.” Palestine with its hospitality, services, and marketing campaigns should try to be the “good perfume,” according to the imagery of the Persian Shaykh Muslih al-Din Sa’di, who in his ethical treatise The Rose Garden asserts, “The perfume seller needs not boast about the quality of his merchandise, since the fragrance of the flowers is its own witness.”