By Ahmad Junaid Sorosh-Wali

and Mohammad Abu Hammad

Cultural heritage, in its diverse manifestations that range from historic monuments and urban fabrics to traditional practices and museums, enriches our everyday lives in various manners. In cities, urban heritage encapsulates citizens’ pride and sense of belonging, it nurtures a sense of identity, promotes social cohesion, and may foster openness and inclusiveness. In Palestine, as in the rest of the world, 75 percent of the population live in urban areas.i As cities have become home to the majority of the population, UNESCO has made people central to its mission and has adopted cultural conventions that all have been ratified by the State of Palestine.ii The preservation of urban heritage as an inclusive and common space in which people are given the opportunity to make choices and practice their freedom is particularly needed in Palestine, as it fosters the sense of identity that is facing growing challenges as a result of occupation and globalization. An inclusive urban heritage that is properly preserved is a strong means to transmit Palestinian national identity to future generations.

Urban areas in Palestine are rich with heritage assets. The historic centers in cities such as Jerusalem, Nablus, Hebron, and Bethlehem, as well as the numerous urban archaeological sites that can be found in their vicinities and the associated cultural landscape offer unique and diverse experiences for locals and visitors alike. It is of paramount importance to reveal the potential of all these places to help build an inclusive society with a strong identity that respects cultural diversity. This starts with ensuring access and furthermore implies that the understanding and enjoyment of heritage must be fostered among all social groups, including women, men, boys, and girls on the basis of equality and freedom.

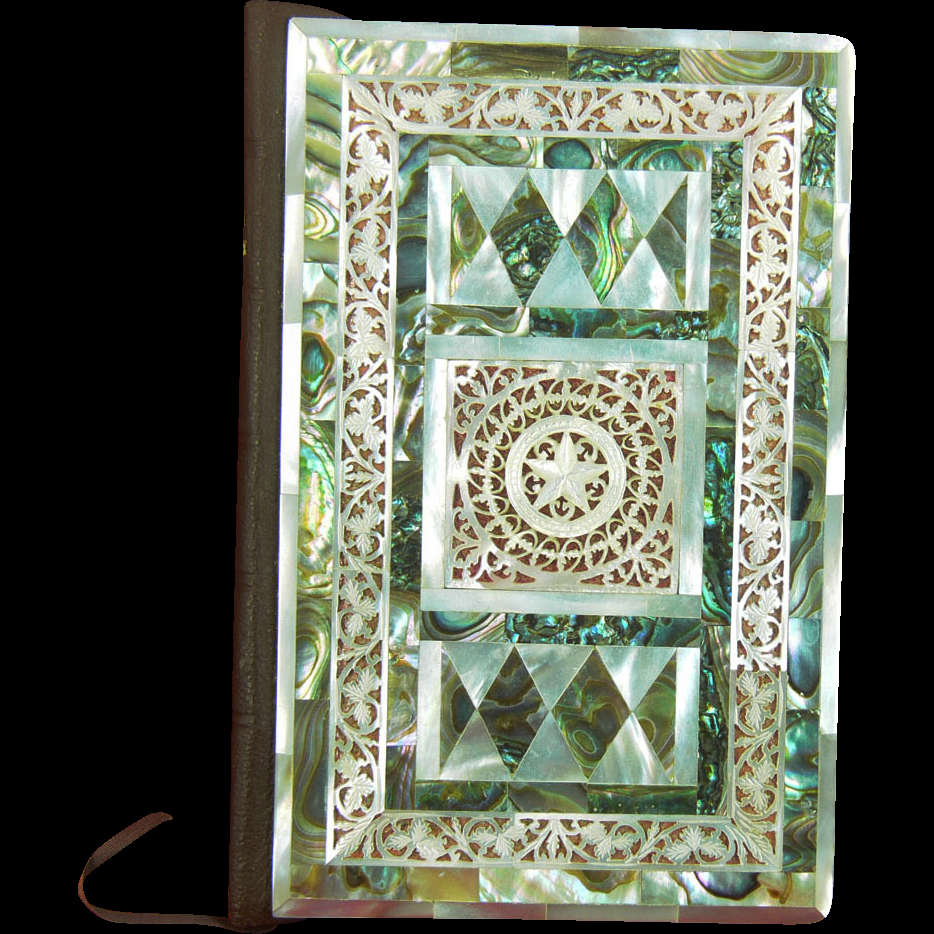

The UNESCO national office for Palestine, through its Culture Programme and in alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, promotes the inclusiveness of cultural heritage in Palestine. Urban heritage in Palestinian cities and towns is the arena to mark a successful experiment in this regard, despite its relatively small area in the expanding Palestinian cities. Urban heritage can provide places of creativity and offers fulfilment of people’s aspirations for a distinctive living experience as it is built according to a human scale that allows for walkability, interconnectedness, and mixed uses, and has the capacity to provide services in inviting outdoor spaces. In addition, urban heritage places are nodes of economic activities for creative industries and craftsmanship, generating jobs through cultural productions that include, for example, glass, ceramics and pottery in Hebron, olive wood and mother of pearl artifacts in Bethlehem, and soap and sweets in Nablus.

UNESCO’s experience in Palestine, gained through numerous types of cultural heritage projects, reveals the role that Palestinian urban heritage can play in enforcing an inclusive society and identity within cities. Recently, UNESCO worked closely with the Palestinian government to prepare two conservation and management plans for the World Heritage Sites “Birthplace of Jesus: Church of the Nativity and the Pilgrimage Route, Bethlehem” and “Palestine: Land of Olives and Vines – Cultural Landscape of Southern Jerusalem, Battir.”iii As the purpose of these plans is to provide effective management of the sites for sustainable use, UNESCO called for and assured the development of management systems that are people-centered, embrace public knowledge and know-how, promote free access and use of heritage places, and secure their adequate conservation and transmission to future generations.

Other recent examples of the role of urban heritage as inclusive places and constituents of identity are the Old Town of Nablus and Sebastiya, which are among the 13 sites listed on the Tentative List of Palestine,iv a list that comprises the properties that Palestine considers for future nomination to the World Heritage List. At the request of the Palestinian government, UNESCO has provided technical support by addressing challenges to urban development in the archaeological sites of the Roman Hippodrome and Amphitheatre, which are in the proximity of the Old Town of Nablus and an integral part of the site listed on the Tentative List of Palestine as “Old Town of Nablus and its environs.”v An urban development program was proposed by private developers over the archaeological site without taking into account the unquestionable cultural value of the site and its importance for the city’s inhabitants and identity. Even though they are located on privately owned property, and without undermining the owner’s rights, UNESCO has called on the Palestinian government to conserve the site due to its unique heritage values, proposing to turn it into an archaeological park that is accessible to all. A heritage site in the heart of the city can play a great role in educating youth and in promoting social inclusion through hosting public meetings and diverse communal activities.

UNESCO is actively engaged in preserving Palestinian cultural heritage to foster a strong sense of identity among current and future generations and to provide public spaces that promote social cohesion based on the principle of inclusiveness.

Even when sites are in a degraded state, the proper attention of people and authorities can transform urban heritage into public venues that help compensate for the lack of inclusive urban spaces in today’s Palestinian cities. UNESCO realized this in 2014 in the Nablus area, when the abandoned archaeological site of Tell Balata,vi identified with the ancient Shechem and containing unique remnants from the Middle and Late Bronze Ages – dating from around 2000 until 1100 BC – was transformed into an archaeological park that provides explanations and historical background and features a visitor’s center. Built after comprehensive conservation research and with proper management, the venue has enabled the local community to reconnect with the site, encouraging individuals and groups to interact and better understand the significant role of the site and cultural heritage in their lives.

The same applies to the Roman Forum in Sebastiya, which is an open space that awaits the possibility to reclaim its ancient central role as a gathering space and venue for social negotiations. The Palestinian government is implementing an optimistic program that aims to regenerate the historic town in Sebastiya and the surrounding villages, and thus looks at the potentials of such a space. UNESCO, while supporting this initiative, advises the Palestinian government on suitable ways of applying physical interventions in the forum without undermining its values. Guiding principles, developed by UNESCO and approved by the Palestinian government, were shared with the project’s designer architect. They emphasize the main principles of creating a communal heritage space accessible to all social groups on the basis of equality, while meeting local economic development needs.

As Palestinian urban heritage is a significant part of the identity of the cities and peoples, the demands for its preservation is increasing day by day. Socio-economic needs, urban pressures, and neglect, if they continue at the current pace, will deprive this heritage of its strong and attractive values. The preservation of inclusive urban heritage will not only protect its physical assets, it will also transmit its spirit in forms of diversity and pluralistic traits for future generations, hence transmitting an intact identity.

i UN Habitat: https://unhabitat.org/books/first-state-of-palestine-cities-report-recommends-national-urbanization-policy/.

ii The 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention (Accession March 22, 2012); the 1954 Protocol to the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (Accession March 22, 2012); the 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (Ratification March 22, 2012); the 1972 Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (Ratification December 8, 2011); the Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, March 26, 1999 (Accession March 22, 2012); the 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (Ratification December 8, 2011); the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (Ratification December 8, 2011); the 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (Ratification December 8, 2011).

iii Palestine: Properties inscribed on the World Heritage List (3), UNESCO, available at https://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/ps.

iv Available at https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/state=ps.

v Tentative List: “Old Town of Nablus and Its Environs,” UNESCO, available at http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5714/.

vi More information about Tel Balata Archaeological Park project and site’s history is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TB4vaRrHk38 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2n_dbYJTxH0.

Ahmad Junaid Sorosh-Wali is the head of the Culture Unit and a Culture Programme Specialist at UNESCO Ramallah Office. He has worked with UNESCO since 2003, first in the Tangible Heritage Section until 2005, then at the World Heritage Centre as Focal Point for Western, Nordic, Baltic and South-East Mediterranean Europe before joining UNESCO Ramallah Office. Mr. Sorosh-Wali holds a master’s degree in architecture and another in heritage conservation.

Mohammad Abu Hammad is an architect and urban planner, holding a bachelor’s degree in architecture from Birzeit University and a master’s degree in urban studies (4CITIES in Urban Studies) from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. He has 13 years of experience in the fields of architecture, urban planning, and cultural heritage in Palestine. He currently works as a project coordinator in the culture unit at UNESCO Ramallah Office.