Since the 1970s, Jerusalem has, for the most part, been shelved as a final-status agenda item in negotiations on the Palestinian state. Fast forward to 2015: the number of Israeli settlers in East Jerusalem has grown from 8,649 settlers in 1972i to more than 200,000 today. Over the years, the Israeli Occupying Power adopted policies to aid its colonialist and expansionist plans across Palestine, particularly focusing on Jerusalem. Such policies and practices have proved detrimental for the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem and have particularly served Israel’s public policy to establish a Jewish majority in Jerusalem by changing the demography of the Holy City.

If we hold to international law, partial solace can be found in a coherent framework from which we can draw that Israeli settlements, and the expansion thereof, in occupied Palestine – including East Jerusalem – is absolutely unlawful. The law of occupation, as per the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention and the 1977 Additional Protocol I, clearly sets out that the Occupying Power is prohibited from transferring parts of its civilian population into occupied territoryii and would be in grave breach of international humanitarian law if it were to carry out such an act.iii Similarly, it is considered a war crime under the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) for the Occupying Power to directly or indirectly transfer its civilian population into occupied territory.iv Regardless, the Israeli government continues with its settlement expansion in East Jerusalem and the rest of the West Bank while providing unlawful privileges for settlers that include an institutionalized culture of impunity when violence is instigated against Palestinian civilians.

International law is clear. It recognizes the prolonged occupation of Palestine, including East Jerusalem, and is, therefore, an indispensible tool for Palestinians. Unfortunately, we have many Israeli policies to challenge in East Jerusalem and elsewhere in occupied Palestine using international law. It is not only through transferring its civilian population into occupied territory that the Israeli authority acts towards its goal to alter the status of Jerusalem, in violation of international law. Other policies can also be challenged, for example, those involving the extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly in East Jerusalem. Such destruction is considered a grave breach under Article 147 of the Fourth Geneva Convention and a war crime under the ICC Rome Statute.v

During the last four years, 251 homes were subject to administrative demolition in East Jerusalem due to the lack of a required building permit from the Israeli authorities.vi These demolitions led to the forcible displacement of 839 Palestinians. You might ask: Does this destruction have a legal basis, and does it correspond to a military necessity, or is it a deliberate and an unprovoked destruction? And if so, can we hold Israeli officials to account, particularly at the ICC, for their destruction of Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem? These are important questions, especially in light of Palestine’s recent accession to the ICC Statute on January 2, 2015.

To answer the aforementioned questions, we must first clarify the responsibility of the Occupying Power. Under international law, the Israeli Occupying Power has a responsibility to administer the territory it occupies without changing the existing order. In the keeping of public order and safety, the administration of territory must also be carried out for the ultimate welfare of the occupied territory’s inhabitants,vii and here, for the welfare of the Palestinian population. If we assess Israel’s policies and practices in East Jerusalem, including that of transferring its civilian population therein, we find an inherent failure on the part of the Israeli authority to fulfill its legal obligations towards the Palestinian population and to uphold international law more generally. Such failure is exemplified in the unilateral declaration that the whole of Jerusalem, including East Jerusalem, is the “unified and undivided capital of the State of Israel,” as enshrined in Article 1 of the 1980 Israeli Basic Law on Jerusalem.

♦ International justice mechanisms are key for the exercise of Palestinian sovereignty over the occupied capital of Palestine.

Prior to the 1980 Israeli law until today, the Occupying Power has long prohibited the natural growth of the Palestinian population in East Jerusalem both directly and indirectly. By taking on roles such as issuing building permits, designating planning areas, and providing services for selected parts of East Jerusalem, the Israeli authority – namely the Jerusalem municipality – restricts Palestinian growth in the city. For example, in Israel’s Jerusalem “Master Plan,” the Jerusalem Municipality unilaterally determines the parameters of the city to include selected Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem. Looking ahead to 2020, we see that the plan also allocates a significantly larger construction capacity to Israelis in West Jerusalem and East Jerusalem settlements in order to maintain a 60 percent Jewish majority over the city as a whole.viii In implementing this plan, the Jerusalem Municipality confirms an Israeli-driven system of apartheid in the city.

Discrimination is also evident upon examination of water infrastructure and distribution in East Jerusalem. In a recent example, the Israeli authority has been restricting regular supply of water for over ten months in several Palestinian areas of East Jerusalem such as Shu’afat Refugee Camp. Such restrictions contradict Israel’s responsibility to adhere to the welfare of the occupied population in East Jerusalem, which would require – at the very least – consistent access to water. It would also require an ability to build houses and infrastructure and to expand naturally. But with only 50 to 100 building permits granted per year to Palestinians and the considerable expense of applying for a permit or purchasing land in East Jerusalem, the Israeli system prevents Palestinians from natural growth. This is in stark comparison to the growth in the settlements of East Jerusalem, where housing units are available for Israeli settlers on demand and at lower costs that are tax deductible.

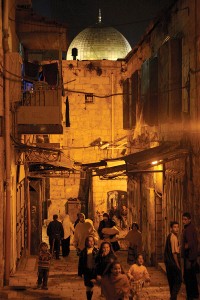

As one travels through East Jerusalem, the impact of the Occupying Power’s unlawful and discriminatory housing system is palpable: sizeable swaths of land extend horizontally for the expansion of settlements, while Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem only extend vertically – often without the required permits – due to a limited space to grow. With a lack of building permits in East Jerusalem, Palestinians therein are virtually left with two choices. One would be to move to the “other side” of East Jerusalem, beyond the Annexation Wall where there is no control on building, and the other would be to continue building homes in the Israeli-monitored side of East Jerusalem without an Israeli building permit, risking a home demolition.

The “other side” of East Jerusalem is an unlawful Israeli construct created after the strategic divide of East Jerusalem through the building of the Annexation Wall with an associated regime of checkpoints and settlements that cut through the eastern part of the city. This created a trap where nearly 150,954ix Palestinian Jerusalemites found themselves not only physically cut off from the rest of East Jerusalem but also cut off from basic services such as garbage collection and phone services – despite paying equal taxes as other Jerusalemites. This has also created a divide between families and communities within East Jerusalem, and effectively prevented some families from sending their children to schools and social activities in parts of East Jerusalem where Palestinians still receive greater access to services and in the city as a whole.

♦ On average, more than 100 Palestinians are displaced every year as a result of house demolitions in East Jerusalem.

The choice to move to “the other side,” where the living costs are relatively lower, is a risky move for Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem. While these areas are much less expensive and involve easier access to the rest of the West Bank, there is a looming danger that one day the Occupying Power would, at its own discretion, entirely seal them off and revoke the Jerusalem residency of all Palestinians living therein. This would mean that these Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem would no longer be able to travel into significant parts of the city without an Israeli permit. Access to key healthcare facilities and holy sites such as Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Holy Sepulcher would also be prohibited without an acquired permit. Accordingly, many families in East Jerusalem resort to option two: to build homes without a permit in the Israeli-monitored part of East Jerusalem.

In analyzing the framework within which Israel administratively destroys Palestinian houses in East Jerusalem, the act can be viewed as unlawful and wanton in serving of Israeli public policies and not a military necessity. As such, one can challenge this destruction as a war crime under international law. Significantly, with its accession to the ICC Statute, the State of Palestine lodged a declaration under Article 12(3) accepting the court’s jurisdiction over crimes committed in Palestine since June 13, 2014. This means that the ICC prosecutor can now look at allegations against perpetrators responsible for crimes within its jurisdiction, including war crimes discussed in this article.

On January 16, the ICC prosecutor Mrs. Fatou Bensouda initiated a preliminary examination into the situation in Palestine, providing a vital opportunity for civil-society organizations and other experts to submit legal memorandums supported with preliminary data that would stir the examination in the right direction. While the ICC is not the only avenue for international justice given the principle of universal jurisdiction, the opportunity to engage the ICC is paramount to Palestinian efforts to hold Israel accountable for its unlawful acts in occupied Palestine, particularly East Jerusalem, and to deter further violations of international law that severely impact the lives of Palestinians therein.

» Mona Sabella is a legal researcher and advocacy officer at Al-Haq. She was born and raised in Jerusalem. She graduated from the University of Essex in 2013 with a master’s degree (LL.M.) in international human rights and humanitarian law. Following her studies, she worked briefly with the Human Rights Committee in Geneva before returning to Palestine.

i Source: Foundation for Middle East Peace.

ii Article 49, sixth paragraph of the 1949 Geneva Convention IV.

iii Article 85(4)(a) of the 1977 Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions.

iv Article 8(2)(b)(viii) of the 1998 ICC Rome Statute.

v Article 8(2)(a)(iv) of the 1998 ICC Rome Statute.

vi In the last four years, one punitive house demolition took place in East Jerusalem in 2014. Israel’s policy of punitive house demolitions amounts to collective punishment. The collective punishment of protected persons is absolutely prohibited under Article 33(1) of the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention. Punitive house demolitions can also be considered a grave breach of the Fourth Geneva Convention as they fail to classify as a military necessity under Article 147 of the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention.

vii Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Regulations.

viii The Jerusalem Master Plan 2000 (unofficial English translation can be found on the website of the Coalition for Jerusalem, www.coalitionforjerusalem.org).

ix Source: The Palestine Central Bureau of Statistics.