The pen was held carefully at a precise angle and with an intention the students strained to imitate. Ayed pulled the pen down, illustrating how to create a crisp, straight line – the ink falling heavy black against the stark white of the paper. The students focused carefully on his movements before their eyes moved down towards their own papers, spread out over hand-crafted wooden tables that were situated in a room full of diverse Palestinian art – pottery, paintings, and other sculptural design. Co-founded by Ayed Arafah and Vivien Sansour, El Beir (Arabic for The Well) was created as both an art collective and a home to the Heirloom Seed Library, purposed to promote biodiversity and to preserve the endangered cultural heritage of Palestinian arts.

Generally a place of sharing, learning, and access to historically native seeds, today the shop was transformed into a calligraphy classroom as Ayed wove through the space, observing the students’ work and giving gentle instructions for correction or adjustment. As they tried to copy his work, their papers filled with lines and curves that fell far short of the grace in the arching Arabic letters on his paper. But the students did not seem to mind; they giggled as they tried, failed, and tried again. They spoke with one another and exchanged conversation with Ayed as they went on, asking him questions about how he learned calligraphy, how long he had wanted to start a shop, and if he could tell them more about the Deheisheh refugee camp they had visited a few days ago.

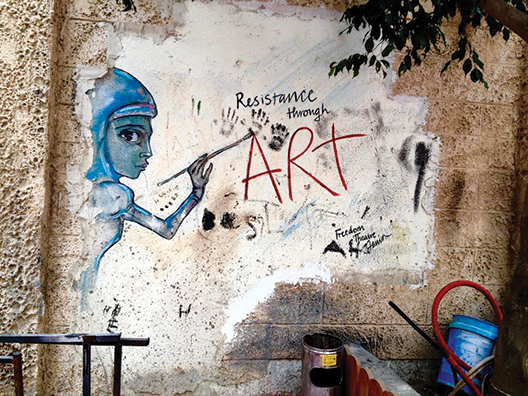

But what difference can a calligraphy lesson make in the wake of a prolonged trauma like occupation? What good can calligraphy pens, crafts, and local art make, when surely there are more pressing issues for a people systematically deprived of necessities as basic as water? After four months of traveling with a group of nineteen- and twentyyear-old international students, I would argue that it makes all the difference. Culture makes all the difference. Cultural resistance does not negate the need for healthy tension or bold and definitive statements; it is not “soft.” Instead, it invites these actions to take place in a context of consideration and criticism, with the intent of creating a refined beauty instead of a deconstructive reality.

While the last fifty years have seen the occupation grow more difficult in increasingly sophisticated ways, it must be noted that the lack of positive progress has existed within a rapidly evolving social context. As such, to the same extent that most realities of the occupation have been left unchanged, our notion of resistance needs to change; it needs to be deepened, needs to be expanded, needs to include calligraphy lessons.

While in Jenin, the same student group met with representatives from the Freedom Theatre. One of our hosts spoke to the critical role of the arts in resistance. “The next Intifada,” he noted, “needs to be cultural.” A diverse resistance – not solely comprised of media posts, and not founded on violence, nor sown with seeds of distrust. It needs less fighting against and more fighting for. For Palestine, yes, but for a further developed definition not only of what Palestine was – what was lost and justice would demand be recovered – but also a stronger message of who Palestine will be. An expanded notion of resistance that extends into the hands of every individual, not only calling upon those who are the most polarized in their views or in their willingness to participate or not in the activism of today. This new resistance will call without exception upon every Palestinian, and it includes the goods they produce, the jobs they create, the poems they write, the plays they act, and each conversation they have.

The students experienced such types of resistance with Ayed, Vivien, and The Freedom Theatre, and again in March, as they sat in Taybeh’s St. George’s Church. Golden sunset-light bathed the centuries-old stones and their faces, still sweaty from their three-hour hike through the valleys around Taybeh. They had spent the early afternoon touring the first Palestinian microbrewery and taking in the state-of-the-art equipment of the correlating winery. Coming from a country that values innovation, creativity, and a worthy craft beer, the students were eager to hear the story of Taybeh Brewery. Instead of being told, they were shown. Instead of being given a textbook with bold headings, they learned the importance of natural resource control through seeing the relevance of water to the micro-brewing process. Instead of reading an article on checkpoints and their effects on exports, they engaged with a firsthand example of a business being forced to deliver its product inefficiently. While Taybeh beer could be delivered to Jerusalem within thirty minutes along a direct route, an expensive six-hour process is required, involving loading, unloading, security checks, and vehicle changes (as Palestinian vehicles are not allowed to enter Israel). The students left that day without memorizing statistics or facts, but with their hearts marked by the experiences of the people of Palestine. And more than the technicalities and specifics of this particular business, they had learned about resilience, as they were interacting with business owners whose commitment to creation proved stronger than the temptation to villainize the systems of oppression that make it a daily challenge to remain a competitive business. Through their business, the Khoury family creates a quality product and provides high-quality jobs, while simultaneously creating optimism and a new understanding of how resistance can look like.

El Beir, Freedom Theater, and Taybeh Brewery are branches of a creative resistance that is growing and needs to be nurtured. If these initiatives are neglected, the Palestinian plight will suffer alongside their unreached potential. They will be compromised as a means for true change. The practice of traditional forms of opposition will raise a generation that is accustomed to fighting against occupation – but with an increasingly blurry vision of what it is fighting for. However, if we invest in creative alternative streams of defiance, then they can provide a transformed face of resistance. A face that appeals inwardly to Palestinians, as it serves as an accurate mirror in which we can see ourselves and our shared future within. At the same time, such resistance appeals externally to the global community due to its explicit non-violence, its cultural development and exultation, and its creativity and innovation.

Entrepreneurship, cultural heritage, theater, writing, music, dance – the examples are plentiful and the possibilities endless. As the students experienced invitation and connection over and over again, they caught a new vision of who Palestine is, and Palestine seemed to know itself a little better as well. So make a product, teach a skill, create something beautiful – with the confidence that its inception is resistance. Teach calligraphy.

Eighteen-thousand-two-hundred-andfifty days of occupation were not redeemed in that calligraphy lesson, but maybe an hour of them was. And so in each conversation, each paint stroke, and every outreach of cultural learning, there is the potential for another advocate who, I trust, cannot help but bear witness to the Palestine of tomorrow. Not because he or she will have been convinced, but because they will have been inspired. May the next fifty years will look different in a way the world cannot refuse.