At the 1992 Earth Summit the governments of the world agreed on a new agenda for sustainable development. This agenda included a bold new Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) which calls on governments to establish systems of protected areas and to manage these in order to support conservation, sustainable use, and equitable benefit sharing. The governments recognized nature reserves as economic institutions that have a key role to play in the alleviation of poverty and the maintenance of the global community’s critical life-support systems.

Nature Reserves are places for people to get a sense of peace in a busy world; places that invigorate the human spirit and challenge the senses. While protected landscapes embody important cultural values, some of them reflect the heritage value of countries, all are important for research and education, and they contribute significantly to local and regional economies, most obviously through tourism and recreation. The protection purpose is to house a diversity of plant and animal species in a delicate balance and in places where human influence is small, in addition to providing shelter, allowing species to move freely, and ensuring that natural processes can shape a landscape.

♦ Since Palestine is part of the Mediterranean Biodiversity Hotspot, a centre of plant endemism, and a refuge for several animal species that are facing multiple pressures in many other areas worldwide, its biodiversity is also part of the global natural heritage. Conservation of this biodiversity is among the high priorities of the Palestinian nation. Hence, a protected area system would be the most promising way of easing key pressures and conserving this valuable biodiversity.

The Palestinian Nature Reserves (NRs) harbor a rich base with many species. When applying the precautionary principle1 for the analysis of Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA) on the Palestinian NRs, we find numbers of them identified as KBAs,2 which highlights the outstanding biodiversity value that is represented by the Palestinian reserves.3 Thousands of people are dependent, at least partially, on the resources and ecosystem services provided by the NRs, which underlines the importance of these areas as part of Palestine’s environmental infrastructure. Additionally, Palestinian NRs are important habitats for several species that are listed as endangered, or even critically endangered, at a global level on the Red List of Endangered Species of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

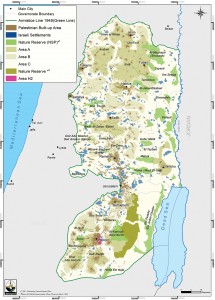

According to the National Spatial Plan (NSP) set forth by Palestinian partner ministries,4 approximately 9% of the West Bank region is designated as nature reserves, forming 511,578 dunums (51,158 hectares).5 Most of these reserves are situated in the Eastern Slopes region (52.9% of the total NR area), followed by the Central Highlands (34.5%), the Jordan Valley (11.9%) and the Semi-Coastal Region (0.7%). The location of the nature reserves within the four eco-geographical regions determines the precipitation that they receive, the habitat types that dominate their location, and other environmental characteristics.

According to the Oslo Accords I and II (1994/95) and the Wye River Memorandum (1998), only nature reserves that are at least partly contained within Areas A and B were handed over to the Palestinian National Authority. They form a total of 83,762 dunums, equal to 16.4% of the total NRs area in the West Bank region (Map 1). Among the most famous and of high biodiversity value NRs are in Area A Siris, Jenin Governorate, and in Area B Deir Ammar, Ramallah Governorate. Nature reserves that are partly situated in Area C – such as Al-Mughayyir, Jenin Governorate; Suba, Hebron Governorate; Tammun, Tubas Governorate, and others – are also partly managed by the PNA ministries, and the personnel employed by the Israeli administration are engaged to coordinate management with their Palestinian counterparts.

However, most of the protected areas are located within Area C,6 where control continues to be under the exclusive authority of Israel. According to the NSP they amount to 81.8% of the nature reserves in the West Bank region, forming 418,570 dunums, with the largest being the Ein Fash’ha-Ein Jedi cluster and the Fasayil nature reserve that form 93,035 and 86,750 dunums respectively (Map 1). None of the nature reserves located in area C are accessible for Palestinians, not even for management and conservation purposes. It is also worth noting that 36.2% of the designated nature reserves overlap with Israeli settlements and 39.5% overlap with closed military areas and bases.7 Such utilization of a nature reserve confirms that their declaration does not respond to the international definition of a nature reserve, which calls mainly for biodiversity conservation.8

It is worth noting that under the Wye River Memorandum, land reserves amounting to approximately three percent of the West Bank were supposed to be handed over to the PA to be set aside as a Green Area/Nature Reserve, with the stipulation that no changes to the land (i.e. no construction) were allowed. To date, the PA has not been allowed to utilize this area.

The main typology of available nature reserves in Palestine includes two types: (1) Wetland reserves containing springs, rivers, streams, etc., such as Fasayil, Ein Al-Beida, Ein Fash’ha, Wadi Al Qilt, Ein Turba, Ein Ghwair, and many others. (2) Dryland reserves contain man-made forest, mixed and natural forest, scrubland, and open spaces with little vegetation, such as Umm At-Tut, Siris, Um Ar-Rihan, Kafr Thulth, Umm Safa, Beit Liqya, Al-Qarin, Abu Soda, Khal Abu Ashara, Al-Alamieh, Wadi Al-Quff, Suba, and many others (Map 1).

Both types of nature reserves are rich with a diverse base of plant species. For example, the wetland reserves are famous for Populus spp., Tamarix spp., and Zizyphus spp., such as the Euphrates Poplar (حور), Tamarisk (اثل), and Christ Thorn (سدر) respectively. In some other reserves, water is more saline; therefore they are famous for Phragmites spp., Suaeda spp., and the Salsola spp., such as the Common Reed (قصب المكانس، قيصوب), Seepweed, Seablites (خوريه), the Prickly Saltwort (الكالي), and others.

The dryland reserves are dominant with natural Mediterranean wood and shrub forests which are famous for Aleppo Pine and Evergreen Oak Maquis. Main tree and shrub species are Oak (بلوط/ملول), Carob (خروب), Pistachio (بطم فلسطيني), and Lentisk (سيريس) trees which are associated with other plants such as Thorny Burnet (البلان/النتش الشوكي), Rockrose (اللباد), Jerusalem Sage (ضرس الشايب الصمغي), Persian Hyssop (زحيف/زعترفارسي), Palestine Lupine (ترمس بري), and many others. Planted forests are famous for Pine (صنوبر الطعام / صنوبر الشائع), River Red Gum (الكينيا), Cypress (سرو), and Acacia (آكاسيا) trees and many others.

The Palestinian NRs are known for their importance in supporting the growth of endemic and endangered species (listed on the IUCN Red List), such as the Dark Brown Iris/Jal’ad Iris (سوسن أسود/ سوسن جلعاد), and Betony/Wounwort (سنبلة) as endemic species, as well as Syrian Sage/Spiny Calyxed Sage (خويخة), and Buplever as potentially rare, and Hare’s Ear (آذان الفار/ حلوان) as very rare species.9

The Aichi Biodiversity targets, issued by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) as part of “The Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020,” defined in its Target 11 that good progress would be made if 17% of the land could be made a protected area.10 At the moment, and including all aforementioned nature reserves in the West Bank region, only 9% of the total land area of the West Bank is designated as nature reserves. It would create the potential for economic opportunity to declare valuable and well-studied nature reserves (upon revision of existing ones) and to set up a number of plans, such as on eco-tourism development, recreation and education, forest restoration, rangeland management, and others to benefit the biological components and local communities at both individual and national levels, and to take into consideration conservation measures.

Roubina Bassous/Ghattas is the Head of the Biodiversity and Food Security Department at the Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem (ARIJ). She graduated from Birmingham University, UK, with an MSc degree in the “Utilization and Conservation of Plant Genetic Resources.” She is an expert in Landscape and Biodiversity Conservation.

» ARIJ is a Palestinian research organization working in the fields of socio-economics, natural resources, biodiversity, water management, sustainable agriculture, and political dynamics of development in the oPt. More information can be found at www.arij.org.

1 Key biodiversity areas are places of international importance for the conservation of biodiversity through protected areas and other governance mechanisms. The KBA concept was set by the international Union for the Conservation of Nature and published under P.F Langhammer, M.I Bakarr, L.A. Bennun, et al., (2007), Identification and Gap Analysis of Key Biodiversity Areas: Targets for Comprehensive Protected Area Systems, Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

2 Seven NRs correspond to KBA Category I, two NRs to Category II, and eight sites to KBA Category IV.

3 International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), (2010), The Palestinian Forest and Natural Resource Assessment, Palestine, unpublished.

4 National Spatial Planning takes into consideration spatial dimension in directing development and geographical distribution for economical and social activities; it was set up by Palestinian ministries in 2012.

5 These areas overlap with the area declared by the Israeli occupation authorities as nature reserves by 187, 817 dunums.

6 Area C was defined under the Oslo Accords as areas where Israel was to exert civil and security control on an interim basis. While the 1995 Interim Agreement called for the gradual transfer of power to the Palestinian Authority (PA), this transfer was never implemented. As a result, any construction, such as an animal shelter or a donor-funded infrastructure project, requires the approval of the Israeli Civil Authority that operates under the Israeli Ministry of Defence. Area C compromises 61% of the West Bank area.

7 ARIJ (The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem) – GIS (Geographic Information System) and RS (Remote Sensing) Department, 2015. West Bank Land Use/Land Cover Analysis 2012, Bethlehem, Palestine.

8 A clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long term conservation of nature, as defined by the international Union for Conservation of Nature (www.iucn.org).

9 M.S. Ali-Shtayeh, and R.M. Jamous, (2002), “Red list of threatened plants of the West Bank and Gaza Strip and role of botanic gardens in their conservation,” Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences Studies, 1/2002, 2: 1 – 47.

10 Convention on Biological Diversity, The CBD Website, UNEP, available at https://www.cbd.int/web/; and Aichi targets available at https://www.cbd.int/doc/strategic-plan/2011-2020/Aichi-Targets-EN.pdf.