Many moons ago, I used to travel frequently to the United States for ecumenical events that addressed conflicts blending secular issues with church-related concerns. Invited by different American churches, be they Methodist, Presbyterian, Catholic, Lutheran, or Baptist, I oft-times found myself not only in the well-known hubs of the East Coast − New York or Connecticut, for example − but also in places such as Texas, Indiana, or Colorado. Those heady days of my younger years were also eye-openers for me. But why?

In most places I visited, I introduced myself as “an Armenian from Jerusalem” and I could see the questions welling up almost instantly in the eyes of many men and women in the church halls or public places. Whether Winter Texans in Austin or Hoosiers in Evansville, the inevitable − almost hesitant − opening questions to me were, “Did you say you are Aramean?” or “So you have Arabian blood?” and to cap it all with an insult to most indigenous Christians who hail from the Levant, “Did our missionaries in the West convert your family to Christianity?”

Aramean? Arabian? A convert? Moi? No! I am Armenian. So once I had explained my roots in a few words, and dispelled some of the more nebulous ideas that were astir in the audience, the real discussions took off.

As the world celebrates the season of Christmas this year, it is inevitable that the eyes of the world will turn at some stage toward Bethlehem, the little town that has become so iconic in our carols. Whether because of spiritual reasons or touristic curiosity, we talk about this town in Palestine and refer not only to the birth of Jesus in a lowly manger, but also to the forbidding walls that surround it and turn the season of peace, hope, and forgiveness (or more loftily, salvation) into one of tension, injustice, and bleakness.

And Armenians are very much part of this fabric of society − be they in Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Ramallah, Beit Sahour, or Jaffa. I know this not only from the history pages but more pointedly from my own grandparents who fled both hearth and home and settled in these hospitable Levantine lands over a hundred years ago as they fled the Armenian genocide that took place in Ottoman Turkey in 1915.

Most Armenians in Palestine speak their own native language. The Armenian alphabet consists of 38 letters and was originally developed in 405 AD by St. Mesrop Mashdots who was an Armenian linguist and ecclesiastical leader. But most of them also speak fluent Arabic and − increasingly – Hebrew, given the occupation by Israel of Palestinian territories that has now lasted for 51 painful years.

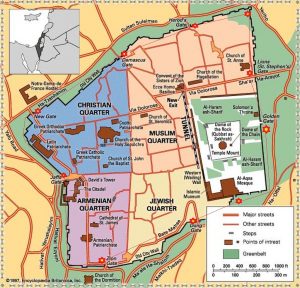

Armenians are also Christian by faith and belong in their majority to the Armenian Apostolic (Orthodox) tradition, although there are a few Armenian Catholic and Evangelical families interspersed in these biblical cities too. In fact, a pilgrim or tourist need only go to the Armenian Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem to come face-to-face with the realities of an Armenian centuries-old presence. The monastery of St. James, which doubles as the seat of the patriarch (or leader) of the Armenian Church, is a constant reminder of the hands-on relevance let alone contribution of the Armenian Church, institutions, and community to the Land of the Resurrection. And if any wayfarer follows the Stations of the Cross (or the Way of Sorrows), the space between the third and fourth Stations (where Scripture tells us that Jesus fell for the first time as he carried his cross) is where one comes across the Armenian Catholic Church of Our Lady of the Spasm that is quaintly known as an exarchate (from the Greek for ruler). In fact, the Armenian Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem, one of four quarters, contains its own school, museum, and seminary for theological students, as well as ceramics and copper crafts shops and restaurants or bakeries that serve Armenian foods. I am sure that many of our TWiP readers will have tried an Armenian pizza or lahmajoun with its spicy smell!

Armenian language and Armenian Christian religion: so does this mean that this community is tucked away in a neat corner of Jerusalem and has no relevance or significance to everyday contemporary Palestine? Were the Americans who listened to my talks across the United States correct in raising their eyebrows or squinting their eyes when I said that I am an Armenian from Jerusalem (part of Jordan when I was born)?

Nothing could be further from the truth. In my opinion, Armenians are very much an inerasable part of the fabric of the overall Muslim-Christian Palestinian society. In fact, to repeat one of my all-too-familiar mantras, Armenians are also Palestinians by culture. This is often overlooked by many commentators, observers, or tourists. Armenians are not a ghettoized “minority” (I dislike this word, even when it refers solely to numbers, because of its negative socio-political connotations!) but rather part and parcel of other Palestinians who share aspirations for peace, freedom, justice, equality, success, and prosperity.

Let me consolidate this statement with some family stories. My paternal grandfather, Vahan, was the first pharmacist in Palestine. His chemist shop was near the Latin-rite Catholic church of The Holy Family in Ramallah. His most famous product was − wait for it − an ointment to treat facial acne that he prepared with his own pestle and mortar and then filled into small waxed boxes for sale. I was practically in diapers when I used to accompany him to the pharmacy and watch him prepare his pharmaceutical concoctions.

How do Armenians fit into the mosaic of different communities or ethnicities living cheek by jowl in Palestine? Do they feel part of the Palestinian topography and culture, or were they unfortunate to have found themselves willy-nilly there? This article echoes the author’s personal views about the Armenian presence in Palestine and underlines the rootedness of this small community to lands that have welcomed them for centuries. For them, this is simply called home.

My maternal grandfather, Ohan, was one of the richest businessmen of his time in Jerusalem. His shop, a landmark for those interested in buying handmade Persian carpets, was opposite the Lutheran Church and a stone’s throw away from the Church of the Resurrection (or Holy Sepulcher) in the Old City of Jerusalem. My olden memories remind me of how I used to “get high” from the smell of those piles of carpets in his shop. As you might have guessed already, my granddad was also the paragon of my younger years.

And if we roll the pages of history forward and stop with the Oslo chapter of the 1990s that was once a ray of hope but ended up being a sad tragedy, four Armenians were instrumental in the public life of Palestine at the time. One was Dr. Manuel Hassassian, who worked with the late Faisal Husseini on the Jerusalem file of the Oslo negotiations. Another was Dr. Albert Aghazarian of Bir Zeit University, who also accompanied Dr. Hanan Ashrawi during the Madrid phase of negotiations. And then there was George Hintlian who was a media wizard and a facilitator for many journalists visiting the country. Add to those Yours Truly who was involved in second-track negotiations on behalf of all 13 traditional churches of Jerusalem. You can perhaps surmise that Armenians were not only an indelible component of the Palestinian reality but were − to be honest − punching above their political weight too.

But Armenian numbers are dwindling fast in Palestine − let alone in other parts of the Middle East albeit for arguably different reasons relevant to each country. Dr. Bernard Sabella, a noted Palestinian sociologist in Jerusalem, often refers to the drop in Christian (and by analogy Armenian) numbers across Palestine. Many Armenians have left Palestine not because they hate the country or dislike its inhabitants or are afraid of a rising tide of Islamist radicalism. They left largely because they faced the same challenges as other Palestinians, namely, that the political realities were becoming increasingly cumbersome, and their prospects were being smothered out as jobs vanished and employment became scarce.

With a presence that dates back many long centuries, and despite the economic woes that are visited upon Palestinians, Armenians still celebrate their history, presence, and witness in these lands − even if at times from afar. And no matter that some quirks in the Christian liturgical calendars mean that Jesus’ birth as well as Resurrection are celebrated by local Christians more than once every year, the fact remains that many Armenian households maintain their attachment to these lands both in terms of a symbol and an identity.

So at Christmastime, when strolling down those cobbled stones across Palestine, or when rambling up its mountains or down its valleys, remember that the scenic land where the prophet Jesus walked, taught, performed miracles, and slept, is one of hospitality for all peace-loving peoples.

And now it is time for me to warm up my own Armenian pizza in the oven! Merry Christmas to All!