The peace process that began in the early 1990s purportedly aimed at reaching a just, lasting, and comprehensive peace settlement through a permanent status agreement that would (among other things) end the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory (that began in 1967) and result in the establishment of an independent Palestinian state throughout the West Bank, including East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip.

As part of this peace process, a series of interim agreements were concluded between the PLO and Israel: the Declaration of Principles of 1993 called for a gradual transfer of power in the Occupied Palestinian Territory from Israel to the Palestinian side over a five-year period, with negotiations on permanent status issues to begin two years after an initial Israeli withdrawal from Jericho and Gaza.1 The Gaza-Jericho Agreement of 1994 called on Israel to withdraw from Gaza and Jericho within a certain period of time.2 The 1995 Interim Agreement contemplated four additional phases of Israeli “redeployments” in the West Bank:3 The first phase was to be an Israeli redeployment from “populated areas” of the West Bank, to be completed before the elections for the Palestinian Council.4 The remaining three phases would involve the gradual redeployment to “specified military locations” over the period of eighteen months from the inauguration of the Palestinian Council, to take place at six-month intervals.5 These interim arrangements were an integral part of the whole peace process, to be concluded with a Permanent Status Agreement, and to lead to the implementation of Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338.6

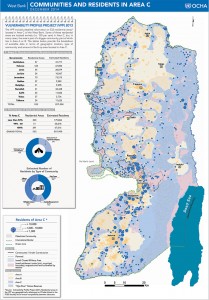

♦ The strategic importance and economic significance of Area C cannot be overstated. It is a natural location for large infrastructure projects such as wastewater treatment plants, landfills, water pipelines, energy projects, and main roads as well as for industrial, tourism and agricultural projects.

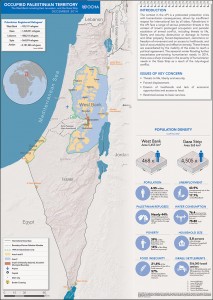

To facilitate the transfer of authority to the Palestinian side, the 1995 Interim Agreement divided the West Bank into three Areas – A, B, and C – and provided that the parties would have varying degrees of authority in each. It provided that Area C, “except for the issues that will be negotiated in the permanent status negotiations (Jerusalem, settlements, specified military locations), will be gradually transferred to Palestinian jurisdiction”7 as part of the three-stage “further redeployments.”8 Notwithstanding the temporary administrative divisions, the interim agreements declared that the West Bank and Gaza Strip comprised a single territorial unit, whose integrity and status were to be preserved during the interim period,9 also providing for a safe passage to link the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.10 But the implementation of the first two phases of redeployment was delayed by Israel, and it failed to carry out the third and final phase of redeployment. Had Israel fulfilled its obligations under the interim agreements in carrying out all redeployments, approximately 92% of the West Bank area would have been under Palestinian control since 1997. Instead, Area A today comprises about 18% of the West Bank territory, which includes all Palestinian cities and most of the Palestinian population; Area B comprises approximately 21% of territory and encompasses small towns and villages in rural areas; while Area C covers 61% of the West Bank territory and is the only area that is contiguous, engulfing the fragmented islands of Areas A and B.

Regarding functional jurisdiction under the terms of the interim agreements: In Area A, the Palestinian government has authority over civil affairs, internal security, and public order, while Israel retains responsibility over external security. In Area B, the Palestinian government exercises civil authority and maintains public order for Palestinians, while Israel retains overriding responsibility for security. In Area C, Israel retains jurisdiction with regards to security, public order, and on all issues related to territory, including planning and zoning, while the Palestinian side has personal jurisdiction over Palestinians and “functional jurisdiction” in matters “not related to territory,” excluding issues that will be negotiated in the permanent status negotiations (Jerusalem, settlements, and military locations).

♦ Considering Area C’s development potential and the fact that it comprises the portion of the West Bank territory that is the largest in size, most fertile, and richest in resources, while taking into account that it is the only territorially contiguous area, it is clear that without Palestinian control over Area C and its development, there can be no viable Palestinian state – nor any prospect for a political settlement based on a two-state solution.

Notwithstanding the 1995 Interim Agreement’s division of the West Bank into areas A, B and C, the status of all the West Bank, including East Jerusalem and Area C, as well as of the Gaza Strip remains that of an occupied territory under international law and as stipulated by the International Court of Justice in its Wall Advisory Opinion.11 The interim agreements do not and were never intended to constitute an acknowledgement of Israel’s claims to sovereignty within any part of the West Bank, whether Area C or otherwise. On the contrary, the interim agreements were intended to formalize a transition from total Israeli control to partial Palestinian control within a period of five years, to be followed by a Permanent Status Agreement that would end Israeli occupation and result in the establishment of a fully independent Palestine state.

As an occupying power, Israel’s powers are only temporary, administrative, and limited in scope, without conferring any sovereign title.12 Sovereignty remains vested in the Palestinian people and the Palestinian state. Furthermore, Israel is obliged to act only for the benefit of the Palestinian population and is prohibited from acting to advance in the occupied territory its own territorial or economic interests, which includes the establishment of settlements and the transferring of its civilian population into the occupied territory.13 Israeli policies and practices in Area C – as well documented by UN agencies, international organizations, and civil society – aim to limit Palestinian access and prohibit development while facilitating illegal settlements and Israel’s exploitation of this area. These practices are in clear violation of international law and of the interim agreements under which Area C should have long been transferred to Palestinian control.

Today, Area C is home to approximately 520 Palestinian communities, 230 of which are entirely located in Area C. The majority of these communities (70%) are not connected to basic infrastructure such as water networks. Palestinian construction is allowed only within the boundaries of Israeli-approved plans that cover less than 1% of Area C. Conversely, land set aside for illegal Israeli settlements and military locations covers 70% of Area C (44% of the West Bank). In addition, 23% of the West Bank is designated as ‘fire zones’ or ‘nature reserves’ by the Israeli military. Similar to lands within the expansive boundaries of settlements and military locations, these lands are considered off-limits for Palestinian access and development. Today, there are 224 illegal Israeli settlements, including over 100 so-called “outposts”, scattered across the West Bank, the majority of which are in Area C.

A case in point for the impact of Israeli restrictions on Area C is the Jordan Valley. In 1967, approximately 250,000 Palestinians lived in the Jordan Valley. In recent years, this number has dropped to 70,000, of which 70% are concentrated in the Jericho area, while approximately 91.5% of the Jordan Valley is considered off-limits for Palestinians. Despite its vast agricultural potential, the Jordan Valley is the governorate least cultivated by Palestinians due to Israeli restrictions. Only 4.7% of the land in the Jordan Valley is cultivated, compared to an average of 25% in other governorates.

A World Bank report published in 2013 on Area C assessed the economic potential of the area to the Palestinian economy.14 The report evaluated the effect of Israeli restrictions on Palestinian planning, zoning, and development of Area C in key economic sectors: Dead Sea minerals exploitation, cosmetics, stone mining and quarrying, construction, tourism, and telecommunications. The conclusions were unequivocal: The direct impact of removing restrictions on the above sectors could generate an additional output of $ 2.2 billion per annum – an amount equivalent to 23% of the Palestinian GDP in 2011. Most of this output could be derived from removing restrictions on two sectors, agriculture and Dead Sea mineral exploitation, with irrigation of unexploited land yielding a potential $ 704 million per year, and exploitation of Dead Sea minerals yielding $918 million per year. The study has also concluded that the multiplier effect across the economy could add a total benefit of $3.4 billion per year and would lead to significant improvements in the government’s fiscal situation by adding $800 million in tax revenues per annum.

The Palestinian government has adopted a Strategic National Framework for development interventions in Area C.15 This framework outlines the national priorities and interventions in Area C across multiple sectors, spanning governance, social sectors, infrastructure, the economy, and the importance of consolidating the efforts of all stakeholders in developing Area C as part and parcel of the territory of the State of Palestine. Building on this government strategy on Area C, the Palestine Investment Fund (PIF), the investment arm of the State of Palestine, has developed a portfolio of projects intended for Area C. These include the development of agricultural production, and of food processing and packaging plants in the areas of Tubas and Sanur; the development of solar farm projects in ten locations in Area C found suitable for that purpose; the development of the shores of the Dead Sea, including mineral production and tourism facilities; residential housing projects in the areas of Qalqilia and Tulkarm, both in Area C, creating contiguity between Areas A and B; a waste recycling site in Beit Furik; a waste burial and recycling site west of Deir Sharaf; a new town in the northern Jordan Valley area to include residential units, an area for commerce and business, and health care and recreational facilities; a new town between Ramallah and Jericho comprised of four thousand housing units; a new neighbourhood in Hebron in the area of Jabel Johar; and the Moon City north of Jericho comprised of residential housing units and recreational facilities.

Against the backdrop of a sharp decline in donor aid, a protracted fiscal crisis, rising unemployment and poverty rates, as well as intensified Israeli settlement activity in Area C, the implementation of these and similar projects in Area C will advance the physical and economic foundations of an independent Palestinian state. It will undoubtedly revitalize the Palestinian economy, create sustained economic growth led by the private sector, and generate thousands of new employment opportunities, all within a developmental approach that goes beyond the humanitarian imperative and accounts for the strategic important of Area C to a viable Palestinian economy and statehood.

» Dr. Mohammad Mustafa is Chairman of the Palestine Investment Fund and is leading PIF in delivering its strategic investment mandate in key sectors of the Palestinian economy. Previously, he has served the PA as Deputy Prime Minister of Palestine and as Minister of National Economy and held a senior position in the World Bank on private sector and infrastructure development.

1. Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, (September 13, 1993), [DoP], Art. V(1) and (2).

2. Agreement on the Gaza Strip and the Jericho Area, (4 May 1994).

3. Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, (September 28, 1995), [1995 Interim Agreement].

4. 1995 Interim Agreement, Art. X(1); Art. XI(2)(a); Art. XVII(8); and Annex I, Art. 1(1).

5. 1995 Interim Agreement, Art. X(2); Art. XI(2)(d); Art. XVII(8); Annex I, Art. I(9); and Annex I, Appendix I, para. B.

6. DoP, Art. I.

7. 1995 Interim Agreement, Art. XI(3)(c).

8. 1995 Interim Agreement, Art. XIII(2)(b)(8).

9. DoP, Article IV; Gaza-Jericho Agreement, Article XXIII, Clauses 6-7; 1995 Interim Agreement, Article XI, Clause 1, and Article XXXI, Clause 8.

10. 1995 Interim Agreement, Annex I, Article X.

11. “The territories situated between the Green Line and the former eastern boundary of Palestine under the Mandate were occupied by Israel in 1967 during the armed conflict between Israel and Jordan. Under customary international law, these were therefore occupied territories in which Israel had the status of occupying Power. Subsequent events in these territories, [including the conclusion of the Interim Agreements], have done nothing to alter this situation. All these territories (including East Jerusalem) remain occupied territories and Israel has continued to have the status of occupying power.” ICJ Advisory Opinion, par. 77.

12. 1907 Hague Convention, Article IV: Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, (October 18, 1907).

13. 1949 Geneva Convention, Article IV: Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War.

14. World Bank Report: Area C and the Future of the Palestinian Economy, (October 2, 2013).

15. State of Palestine: Ministry of Planning and Administrative Development, National Development Plan: State Building to Sovereignty, 2014-1016, available at http://www.mopad.pna.ps/?option=com_content&view=article&id=458&Itemid=142&hideNav=true.