Palestinian architecture, an integral part of our cultural heritage and national identity, is subjected to systematic destruction by the Israeli occupation, which aims to eliminate evidence of the existence of our ancestors on this land.i Preserving our cultural and natural heritage, keeping it alive, and reflecting it in our new designs is part of our national struggle. In light of this, several institutionsii and architectural offices have worked on preserving and revitalizing historic centers and buildings in cooperation with the local governments and the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. The Palestinian Authority has included the preservation of cultural heritage and regeneration of historic centers in its national plans and agenda, in addition to passing Law No. 11 of 2018 (May 3, 2018), which addresses tangible cultural heritage.iii

To achieve resilience, we should seek sustainable development based on our local treasures and resources, including our cultural and natural heritage, local building materials and construction techniques, environmental and vernacular building typologies that respect and respond to the context, and above all, local skills and manpower. The mainstream in architecture practice does not seem to consider these issues but rather is oriented towards investors, detaching architecture from its context and borrowing ready-made recipes just like the rest of the Arab countries in a phenomenon named by Dr. Yasser Elsheshtawy as “Dubaization.”iv Nonetheless, there are projects by some architects that are sustainable and tailored to their context.

As architects, we have a social responsibility towards our community as we should be serving them rather than serving capitalist interests. I believe that architecture serves as a catalyst for social processes, at least in the limited context of local communities, and as expressed in the early twentieth century by Hannes Meyer, director of the Bauhaus School of Architecture, who stressed that as designers, we are servants to the community. Our task is a service to the people. We should be practicing an architecture of social engagement, exploring, agitating, inspiring, motivating, and initiating social processes. We should be encouraging a participatory approach, designing with users rather than for them. Architectural projects should be bound to ethical values and goals rather than serve capitalist and donor agendas.

Such projects are not meant to improve the overall living conditions of a society, but rather serve to change spatially defined situations through tangible architectural means and plans, irrespective of political conditions, and resist the pervasive cultural forces of thoughtless consumption and over-branding of human life. The architecture of acupuncture, where small-scale but socially catalytic interventions that are tailored to the particular environment and community for which they are created and designed to solve local issues, may cause positive ripple effects in this regard and is suitable for our situation.

Ramallah. Photo courtesy of the author.

Although we live within a complicated political situation and difficult economic conditions, where the national agenda is confused between a national struggle for liberation and the illusion of statehood, we fall into the trap of globalization and Dubaization. In the absence of a national plan that is biased towards the poor and low-income sectors of the population, urban development and expansion are driven by the investors’ agenda, prioritizing the building of luxurious suburbs, commercial malls, cafés, etc., rather than developing marginalized areas, building affordable housing, and implementing equitable economic growth projects, which are the responsibility of the government in sovereign states.

Within the current social and political conditions, I believe that architects have a greater social responsibility than ever before. If the built environment is a reflection of our culture, as I believe it to be, architects and designers have an enormous impact upon the direction and focus of the population at large and therefore the formation and maintenance of “culture” through an architecture that resists the addictive and ultimately backward values of a singular global culture of capitalism. Although this requires economic policies and collaborative work, architects are in a unique position to instigate change.

The expansive nature of capitalism is leading us towards a homogenization across previously diverse cultural borders. International, corporate architecture styles consciously ignore regional idiosyncrasies in favor of a singular language. Similarly, artificially conditioned environments disconnect us from regional weather patterns, removing architecture from its place and generating a response that fails to address the sensitive considerations of region-specific design. The answer to all this is Critical Regionalism, which is not simply regionalism in the sense of vernacular architecture. It is a progressive approach to design that seeks to mediate between the global and the local languages of architecture.

By focusing on a return to the local and responsive, we can allow architecture to become a built manifestation of diversity and further encourage society to move in a direction that encourages rather than prohibits variation according to region. This has significant importance in our specific case under occupation, as we should be seeking architecture that supports people’s steadfastness and resilience rather than architecture that encourages consumerism. We need to serve our communities rather than mega-corporations by facilitating their dominance of public space. We should reclaim public spaces to promote a shift in consciousness through direct and participatory engagement, and focus architecture on the act of service.

To bring my words closer to the ground, I will present two projects that embody such positive values: the Moon Cocoon in Jericho, designed by Shams Ard Design Studio, which explores vernacular material and technique as a sustainable alternative to contemporary local building practices, and Bethlehem’s Old Market, designed by Habash Consulting Engineers, who work in cultural heritage preservation and adopt critical regionalism in their new designs.

Moon Cocoon

The building is a quad-dome, 84 square meter private residence, built entirely of earth, using the technique of earth-filled bags. Jericho, where the Moon House is located, prides itself on being the oldest human settlement in the world. Earth construction was used and developed in Jericho over a period of 10,000 years, yet around 50 years ago, earth construction slowly began to be replaced by concrete. Today earth construction and the knowledge around it has all but disappeared. The Moon House is a rare example of a private residence that revives this knowledge.

Designer Shams Ard Design Studio. Photo courtesy of Shams Ard.

To deal with the extreme heat of summer in the lowest spot on the planet, the house uses many passive solar techniques for comfort; it incorporates a natural ventilation technique that utilizes a malqaf, also called a wind catcher, which is a tall, capped tower with openings towards the side from where the wind generally blows. The malqaf catches air, possibly passes it over water to cool it down, and leads it into the living space through low openings. The domed rooftop of the house has operable openings that allow for hot air to escape and (via suction due to lower pressure) be replaced by cool air from the malqaf; this provides a constant flow of air and ventilation. In addition, with a very high thermal mass in the form of meter-thick walls, the house is comfortable even in extreme temperatures. The building, which contains local traditional tiles and all locally made finishes, filters grey water and uses it for irrigation of the surrounding garden.

Revitalization of Bethlehem’s Old Market

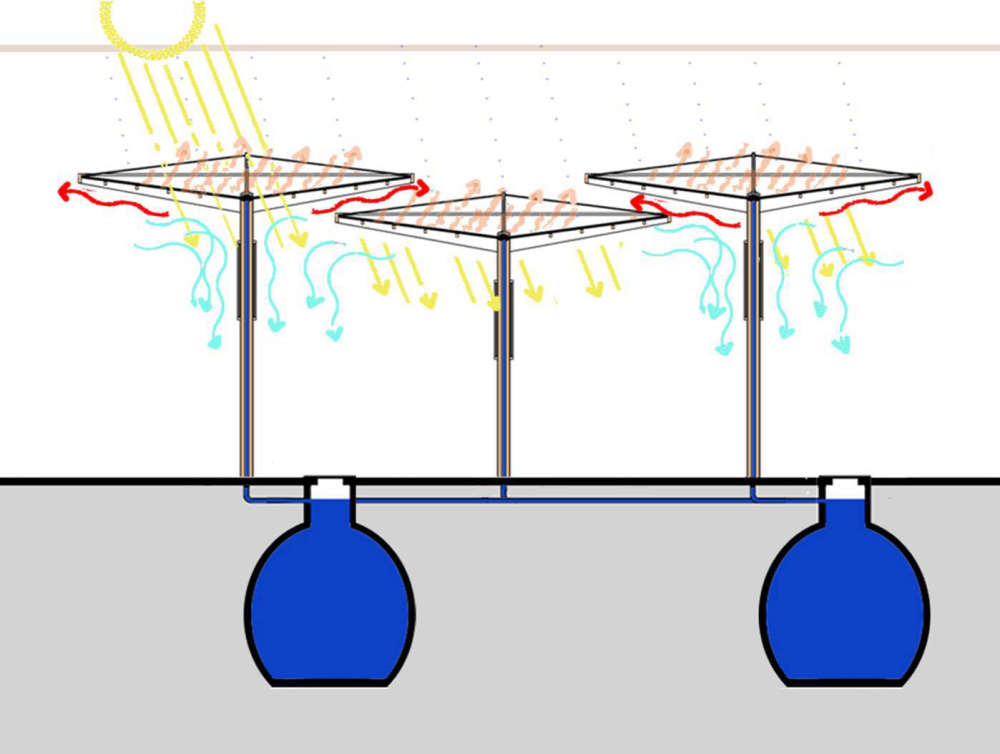

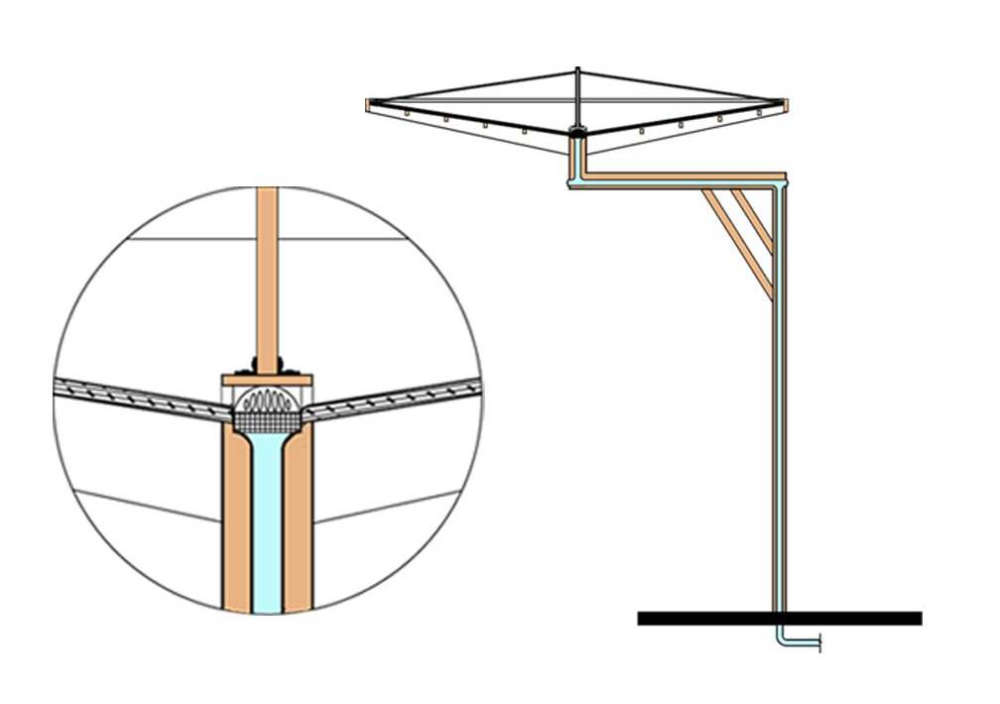

The old market is located in the historical center of Bethlehem (ten kilometers south of Jerusalem) close to the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem Municipality, and Al-Nijmeh Square (Manger Square). It suffered from various problems before rehabilitation, including unorganized access, mixed vehicle-pedestrian movement, random vendors and villagers selling their crops, inconvenient coverage of the market that failed to protect from weather conditions, inconvenient stalls, inappropriate infrastructure and pavement, undrained surface water, lack of public toilets, an open garbage dump, and inadequate accessibility for mobility-impaired individuals. The aim of the project was to revitalize the market by creating a comfortable environment for both sellers and shoppers while maintaining its original spirit, and to create an attractive focal point in the old city of Bethlehem not only for local visitors but also for tourists. The designer set the following principles as design guidance: authenticity, reversibility, durability, flexibility, inclusivity, environmental friendliness, quick construction, locally manufactured.

The design was responsive to a complicated context and implemented with the participation of the various stakeholders, sellers, and users of the market. Environmental solutions were used not only to protect from sun and rain but also to collect the rainwater that could be used for cleaning the market and flushing toilets – important given the general water scarcity in Palestine. Locally manufactured mushroom canopies were assembled on site. Their design was inspired by the colorful existing canvases that had been used for shading, simulating, and respecting the mosaic-like urban fabric of the old city, rather than installing one big structure to cover the entire area. Selectogal transparent yet heat-proof material – in the same colors as the previous canvases – was used to make the canopies in order to allow sufficient light to enter yet prevent heat. Unfortunately, no awareness campaigns were held by the municipality during the construction period or after, which led to misuse of these canopies, as people thought that they were not heat proof. In addition, it is worth mentioning that the design was inclusive and accessible.

Architect = Servant of the Community;

Starchitect = Servant of Capitalists.

These projects are manifestations of critical regionalism versus globalization of architecture and examples of the adoption of social responsibility by architects. More solutions in this vein need to be created and implemented to preserve our heritage and environment, and to strengthen Palestinian society in its struggle to assert its identity and cohesion.

i In 1948, in order to create the “State of Israel,” Zionist forces attacked major Palestinian cities and destroyed some 530 villages. Approximately 13,000 Palestinians were killed in 1948, with more than 750,000 expelled from their homes, becoming refugees – this registered the climax of the Zionist movement’s ethnic cleansing of Palestine.

ii They include Riwaq – Center for Architectural Conservation, Ramallah; Centre for Cultural Heritage Preservation, Bethlehem; Hebron Rehabilitation Committee; the Welfare Association Taawon, Jerusalem; and several architectural and engineering offices.

iii Nevertheless, and even though Palestine signed on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and adopted Goal 11, “Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable,” the economic policies of the PNA are (largely inevitably) donor-oriented, following the World Bank polices, rather than endorsing sustainable development. See Ahmad El-Atrash, “The ‘Urban’ Sustainable Development Goal: Towards Sustainable Cities and Communities in Palestine,” This Week in Palestine, November 2017, issue 235, available at https://www.comunicazionearezzo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/The-%E2%80%9CUrban%E2%80%9D-Sustainable-Development-Goal.pdf.

iv Dr. Yasser Elsheshtawi, “Constructing Imaginary Dreamscape: The Dubaization of the Arab World,” a lecture presented at the symposium titled Land of Dreams to Dreamland: Dream of a State to a State of a Dream, #1 Biennale Architecture Orléans, 2018.