On this 70th commemoration of the Nakba, it is necessary to take stock of the current realities. One fundamental truth is that the Nakba is ongoing; in other words, the Nakba is not an isolated reality that refers only to the historic events of 1948. It is an ongoing phenomenon. The international community continues to both witness and ignore the ongoing displacement and dispossession of the Palestinian people that were initiated during that time. The result is the creation, sustainment, and augmentation of the largest and longest-standing displaced population in the world, constituting 66 percent (8.26 million) of the Palestinian people. Today, there are approximately 7.54 million Palestinian refugees,i in addition to at least 720,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs).

This situation is the result of a vicious cycle of ongoing displacement and simultaneous prevention of return – a cycle that is fueled by a plethora of Israeli policies, practices, and laws that have culminated in a colonial and apartheid regime that perpetrates population transfers to alter the demographic composition of Mandatory Palestine and annexation of its historic lands. Population transfers are prohibited according to international human rights law and international humanitarian law, particularly if perpetrated in order to unlawfully annex territory and/or alter the demographic composition of that territory. Population transfers encapsulate both the implantation of a foreign population into a territory and the forced displacement of the indigenous/habitual residents out of or within that territory.

International law and existing treatises on reparations are based on four principles; namely, voluntary reparation in the form of physical return to the place of origin; property restitution; compensation for damages that include benefits lost and non-material damages; and victim satisfaction, which includes guarantees of non-repetition.

Once displacement occurs, obligations fall upon the perpetrator and the international community to right this internationally wrongful act through the exercise of the right of return. The right of return is fundamental in the Palestinian context as it is both an individual and a collective right, intrinsically connected to the right of self-determination. It must be noted that any attempt to secure self-determination without addressing the right of return of the 8.26 million displaced Palestinians would be futile. In other words, how can Palestinian self-determination be achieved if the majority of the people are not allowed to exercise their right of return? As such, the right of return of Palestinian refugees and IDPs is an elemental facet of the right to self-determination of the Palestinian people.ii

Reparations have implications both in principle and in practice.

According to international law, the principal notion of the right of return is founded upon the free will of displaced individuals and groups: it is based on the rights of residency, adequate housing, safety, and freedom of movement. Further, the right of return is independent of refugee status, nationality, or the causes of displacement and was created for the purpose of preventing and addressing situations of statelessness and population transfers. The refugee or IDP condition is created by the commission of human rights violations by states or other actors under its jurisdiction, and/or the failure of states to ensure national protection for people under its jurisdiction. The absence of national protection arising from state-perpetrated human rights violations or the actions of non-state actors leads to a situation in which displacement occurs. Ensuring protection of persons in need of it becomes an international responsibility when the state in question is unwilling or unable to ensure it. In other words, international protection through international intervention is triggered by Israel’s unwillingness to provide and ensure protection for the Palestinian people under its jurisdiction. First and foremost, the task is to prevent the creation of forcibly displaced persons, but if a person or group is forcibly displaced, then the task becomes ensuring the right of return in order to right the wrong committed.

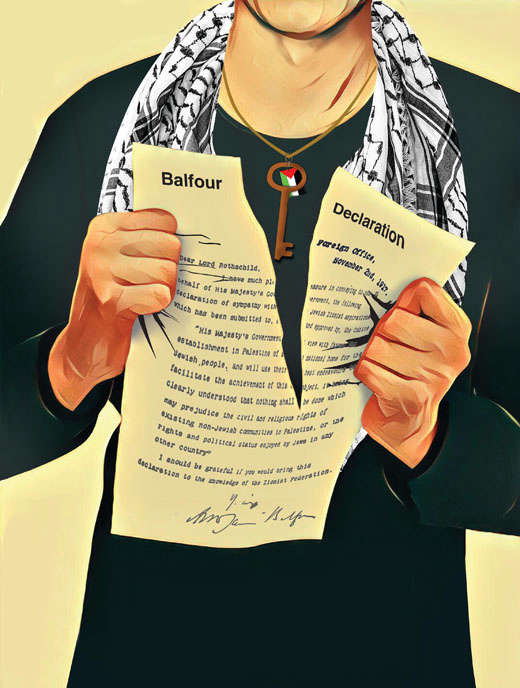

Courtesy of Badil.

With regard to a reparations mechanism, the establishment and/or maintenance of security and stability are important concerns in deciding how but not whether to implement reparations. Justice and access to legal redress are important components of stability and security. The right to reparations was designed to achieve exactly that: restoring as much as possible what once was, and eliminating apartheid and the colonial practices and/or legislation that caused the internationally considered wrongful act(s) in the first place. It goes without saying that refugee and IDP repatriation must be gradual and orderly. It must be carried out according to tested and established mechanisms, taking into consideration the equitable redistribution of property and ensuring social and economic integration of returnees.

National legislation needs to adequately reflect and address reparation-related issues and not be discriminatory in nature or practice. As such, the question of the nature of the state that will receive Palestinian refugees and IDPs is of the utmost importance. A state that is democratic, participatory, and inclusive can embrace all peoples and ensure rights for all regardless of their religious affiliation. The current Israeli regime, however, employs discriminatory national legislation and practices that constitute colonialism and apartheid. It is necessary to dismantle the apartheid colonial regime and replace it with a democratic and inclusive one that respects the rights of all peoples. Hence, the nature of the state that is required is one that ensures equality and equity for all regardless of religious affiliation, ethnicity, race, or demographic composition.

The right to reparations of forcibly displaced persons, according to the frameworks of international law and other treaties on reparations, consists of four main elements. The first is voluntary repatriation, which is the physical return of the victim(s) to their places of origin. Note that repatriation must be voluntary: this includes the right not to be displaced against one’s will, the right to freely choose to return, and the right not to be forced to return. The second element of reparations is property restitution, which is the reclamation of original properties lost by the victims. The third element is compensation for property damage, for benefits lost by the victims due to the loss/denial of use of their property and for non-material damages (such as pain and suffering of victims). And the last element is victim satisfaction that includes, among other things, guarantees of non-repetition. The elements of reparations were established to ensure the restoration as much as possible to what once was for victims of forced displacement and transfer. As such, the elements are indivisible, and a reparations package must include all the elements for it to be successful and effective so that the consequences of forced displacement and transfer can be reversed. Successful reparations mechanisms employ an aggressive property restitution mechanism rather than monetary compensation in order to address ethnic cleansing, racially based spatial segregation, apartheid and/or colonial domination, which are precursors to the refugee or IDP condition. In addition, property restitution requires fewer financial resources than a pure compensation approach.

Property restitution, as a component of reparations, remedies dispossession through reclamation of the original property lost by the original property owner. After 1948, Israel created and implemented the Absentee Property Law that stripped Palestinian refugees and IDPs of their property. Accordingly, Palestinian victims of a state-sponsored discriminatory land regime have the right to property restitution from the state. This means that Israel is responsible for the return of all properties to Palestinian victims who seek property restitution and for the compensation of those who don’t. One of the arguments proposed by Israel is that there is not enough land to accommodate large numbers of returnees and subsequent property restitution. This is not accurate; as a matter of fact, there are significant tracts of land on which Palestinian villages existed that are still not populated, and the land is available for reclamation. According to Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 92 percent of Israelis live in urban areas.iii It should also be noted that significant amounts of land are in the “public domain”; in other words, 93 percent of the land in Israel (about 4.8 million acres or 19.5 million dunams) is either the property of the state, the Jewish National Fund, or the Development Authority. This land is managed by the Israel Land Authority, whose policy is dictated by the Israel Land Council.iv

Ensuring protection for forcibly displaced persons through the exercise of the right to reparations becomes an international obligation when the state in question is unwilling or unable to provide it.

In cases of secondary occupancy, where the original property (whether home or land) is occupied by Israeli Jews, international law and best practice are very clear. Not all property rights are equal: secondary occupancy rights would not block refugee or IDP return and/or restitution. Israel is responsible for ensuring alternative housing for the secondary occupants in cases where refugees and IDPs seek property restitution. Further, if the property was acquired in good faith by the secondary occupant, then he/she is entitled to compensation. However, if the property was not acquired in good faith (where the property was directly confiscated by the secondary occupants or through racially discriminatory allocation of propertyv), then it is not reasonable to prioritize secondary occupants’ rights over those of the victims. However, either with or without good faith, the state is under an obligation to ensure property restitution and compensation to victims and to secure the rights of secondary occupants with alternative housing.

Another point to note with regard to property restitution and the numbers of Palestinian refugees (and their descendants): a mechanism needs to be developed and put in place to equitably reallocate the original property to a larger group of victims. For example, if a Palestinian from XYZ village owned 1,000 dunams of land but he and his descendants now number 120 refugees, a mechanism to distribute the land among the 120 needs to be developed and implemented. This would naturally require the participation and engagement of the refugees and IDPs themselves to determine modes and mechanisms of distribution.

In summation, reparations go hand in hand with sustainable post-conflict reconstruction – not just political, physical, or structural but legal, ideological, social, and economic reform. Reparations were designed to restore a lost right, to restore the lost physical property (and/or equivalent and/or monetary compensation), to promote justice and reconciliation, and to ensure that the process contributes to an economic uplift. However, in order to get to this stage of the process there are certain preconditions that must be met: the recognition of Israel’s historical and continuing role in the augmentation and sustainment of the Palestinian refugee and IDP condition through an ideology – policies and practices embedded in forcible transfer, colonialism, and apartheid; the necessary interventions of the international community to bring Israel into compliance with international law through fulfillment of its obligations, including the dismantling of colonial and apartheid ideology and elements within the Israeli regime, and determining and establishing a viable implementer of reparations for the Palestinian people, which includes their active and meaningful participation.

While the current conditions are not conducive to achieving just and durable solutions to the Palestinian refugee and IDP situation, e.g., the implementation of the right to reparations, we need not wait for these preconditions to be met or a robust peace agreement to be exacted to prepare for Palestinian return. It is paramount that preparations for refugee and IDP reparations begin now in order to be optimally successful. We can start with extensive awareness and education campaigns focusing on the principles and best practices of return; engage Palestinian civil society – especially refugees and IDPs – in developing reparation models and mechanisms, including for property redistribution and compensation; and discuss, debate, and determine the characteristics of the state, its legislation and governance mechanisms. The role of human rights bodies and organizations, in addition to the above, is to continue to document both past and present human rights violations and crimes perpetrated by Israel and to advocate for measures to end impunity and ensure accountability. The role of the international community is to respond with appropriate and practical measures to hold Israel accountable and to provide protection to the Palestinian people from further forced displacement and transfer.

i The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics in 2016 cites 5.87 million registered Palestinian refugees and 1.66 million unregistered refugees. See “Ms. Ola Awad, President of the PCBS, reviews the conditions of the Palestinian people via statistical figures and findings, on the eve of the sixty ninth annual commemoration of the Palestinian Nakba,” available at http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/post.aspx?lang=en&ItemID=1925.

ii For more information on the right of self-determination of the Palestinian people, see the report of the United Nations, “The Right of Self-Determination of the Palestinian People,” January 1, 1979.

iii Letter from Israel: Urban and rural life, Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2010, available at http://mfa.gov.il/MFA/AboutIsrael/Pages/Looking%20at%20Israel-%20Urban%20and%20Rural%20Life.aspx.

iv The chairman of the council is Israel’s vice prime minister, the minister of industry, trade, labor and communications. The council is composed of 22 members: 12 represent government ministries and 10 represent the Jewish National Fund; see About Israel Land Authority, available at http://www.mmi.gov.il/envelope/indexeng.asp?page=/static/eng/f_general.html.

v For example, the Jewish National Fund acquired a great deal of property through land sales that were illegal (even under Israeli law). This property was then leased to Israeli Jews since “ownership” in Israel refers to a lease contract of 49 or 98 years in duration.