Palestinians are among the most aid-dependent peoples in the world. In the West Bank and Gaza Strip, international aid helps fund every aspect of life – food, shelter, education, health, culture, government, and more. However, international humanitarian law states that Israel, as the occupying power, is responsible for ensuring the wellbeing of the protected population. For this reason, critics argue that international aid relieves Israel of its obligations and subsidizes the Israeli occupation, thereby implicating donors and aid actors in Israeli violations of Palestinian rights.

In fact, the international community’s prolonged reliance on aid as a substitute for effective political intervention lets Israel off the hook in two ways: Israel is spared the full cost of the occupation and is not held accountable for its violations international humanitarian law (IHL) towards the protected population. Crucially, accountability is an obligation of third-party states, and the international community is failing to fulfill its obligation to hold Israel accountable.

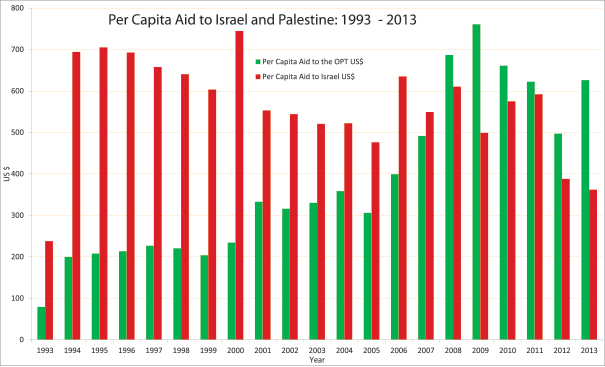

The international community does not intend to be complicit in the Israeli occupation, nor do they wish to prolong it. Yet they face a dilemma. Since the Palestinian market is captive to the Israeli market, a proportion of the aid given to Palestinians will inevitably reach the Israeli economy and be used to bolster Israeli political activities. Up to now, it had not been clear just how much Palestinian aid ends up in the Israeli economy, nor did we know the extent to which this aid subsidizes the occupation.

♦ The shocking fact that for more than two decades the majority of international aid to Palestinians has ended up in the Israeli economy, makes it clear that donors and aid actors should take a closer look at current aid policies and make profound changes to ensure that Israel is not rewarded for its prolonged occupation.”

In new research commissioned by Aid Watch Palestine (www.aidwatch.ps), Shir Hever, an expert on the economics of Israeli occupation, concludes that at least 78% of international aid to Palestinians ends up in the Israeli economy. He explains that several factors help transform Palestinian aid into an important export sector for the Israeli economy, a source of foreign currency for Israel, and a source of income for many Israeli companies. These factors include: (1) The 1994 Paris Accords that created conditions for aid organizations that are conducive to sourcing materials from Israeli companies; (2) Israeli mobility restrictions that result in reliance on Israeli transportation services; and (3) Israel’s currency and customs union which forces cash and in-kind aid to flow in Israeli currency. Hever explains:

Palestinian economic dependency on Israel makes it impossible to differentiate between legitimate and non-legitimate purchases of Israeli goods by aid agencies managing projects in the OPT. In ordinary aid scenarios (such as relief following natural disasters), aid agencies spend a portion of their budget to source goods and services from neighboring countries. In the case of Israel/Palestine, Israel is not merely a “neighboring country,” it is the occupying power with the ultimate responsibility under international humanitarian law to meet the needs of the population under its control. Therefore, any form of aid by third-party countries that relieves Israel of its obligations, or even pays the Israeli government or Israeli companies for goods and services which the Israeli government is obligated to provide, are considered here as a form of aid subversion.

Hever finds that at least 78% of aid money to the West Bank and Gaza is subverted by use for imports from Israel, thereby covering at least 18% (and up to 31%) of the costs of the occupation for Israel.

Aid subversion is only one way that Israel benefits from Palestinian aid, according to Hever’s research. “Aid diversion,” he says, is aid that goes directly to Israel and never provides benefit to the Palestinian population. He includes Israeli measures such as port fees, transportation fees, storage fees, and “security fees” that are paid to Israeli companies or to government institutions from Palestinian aid budgets. For example, Hever cites a 2002 article stating that the largest Palestinian aid distributor, UNRWA, reported that it paid US$ 2.5 million in taxes to Israel in 2001 — nearly 1% of its total budget. A 2011 study of international non-governmental organizations found that Israeli movement and access restrictions on aid delivery cost aid agencies an estimated US$ 4.5 million addition per year, much of that paid directly into the Israeli economy without providing benefit to Palestinians.

The diversion of aid is taken seriously in development practice, and robust legislation and policies exist to address bribery, corruption, terrorism, fraud, and money laundering. Common to all these frameworks is the objective that aid will reach its intended beneficiaries, but what about the situation posed by Israeli diversion of Palestinian aid resources? As it is virtually impossible to calculate the total sums diverted, the magnitude of the problem is unclear. Another separate, but related, issue is aid destruction, as explored by Deborah Casalin. When Israel destroys Palestinian aid projects funded by donors, obliging donors to build again, Palestinian resources are wasted and diverted from their intended purpose.

Richard Falk, a renowned international law and international relations scholar, who recently completed a six-year term as UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Occupied Palestine, was interviewed by Aid Watch Palestine to discuss the legal and human rights implications of Shir Hever’s research. Falk considers both aid subversion and aid diversion as deeply disturbing and deserving of further investigation. In his words, Falk believes that “Perverting the supposed purpose of donor support results in an unfortunate paradox. Rather than rebuilding and restoring the devastation in occupied Palestine, its effect is to normalize and shatter hopes and expectations of a people that has already suffered far too much.”

♦ Aid Watch Palestine is an independent, Palestinian-driven initiative that stimulates and supports efforts to make international aid more accountable to Palestinians – starting with the reconstruction of the Gaza Strip. Aid Watch Palestine invites Palestinians and aid actors – local and international, public and private – to join in critical and constructive scrutiny of aid with the aim of advancing Palestinian rights and long-term solutions.

However, Falk concludes that there is a virtual legal vacuum regarding the responsibility of donor governments to ensure that their funding does not facilitate unlawful policies. Without the political will of donor governments, little can be done. Simply put, international humanitarian law does not specify a clear legal obligation for donor governments to exercise due diligence to ensure that their contributions of foreign aid are not diverted by the occupying power. One exception, Falk notes, is Article 8(2)(b) of the Rome Statute governing the activities of the International Criminal Court that makes it a crime against humanity for there to be a willful blockage of aid to a people or society that has suffered from an unlawful and sustained siege (which clearly applies to the Gaza Strip). In general, Falk believes that the policies of donors regarding Israeli diversions of Palestinian aid do not constitute complicity with Israel’s criminal violations. However, it may be argued, he suggests, that the international community is negligent or complicit by its failure to place international aid in a regulatory framework that imposes rules of responsibility on both donor governments, to ensure that their funding is used as intended, and on Israel as the occupying power, to refrain from unreasonable burdens on aid flows.

Both Hever’s research and Falk’s commentary on it imply that there is a moral and political case for donor responsibility. Falk says, “If donor governments are sincerely seeking to provide economic assistance to the Palestinian civilian population, they should be deeply upset by Israeli behavior and should do their utmost to ensure that their funds are not being perversely diverted to sustain the occupation, rather than to bring it to an end.”

So what can be done? Falk concludes that existing norms, mechanisms, and procedures in international law and the UN system are not robust enough to mount an effective legal challenge to the conduct of donors. Despite this, he strongly favors raising the issue for public discussion:

It still seems important to demonstrate convincingly that moral and political grounds exist to conclude that donor complicity of a persistent character has, for many years, perversely stabilized the Israeli occupation and worked against the realization of the fundamental rights of the Palestinian people, including the right of self-determination.

Falk explains that questions about aid subversion and diversion are complicated by the wide latitude given to an occupying power to invoke security as a justification for restricting and burdening the flow of aid. The imposition of unreasonable administrative charges and taxes are difficult for donors to challenge, given the discretionary nature of international economic assistance. In other words, if the provision of aid is a prerogative of donors, then it will be necessary to overcome their reluctance to legislate or regulate it.

Magelena Sepulveda Carmona, a former Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, argued in a 2009 article that provision of international aid is indeed an obligation of developing states and is subject to binding law under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). She suggests ways to use ICESCR accountability mechanisms to hold donors accountable for compliance with a human rights based approach to aid. It is possible that some of the accountability mechanisms she proposes could be utilized to bring the issues of aid subversion, diversion, and perversion onto the international agenda.

Shir Hever agrees that even if current legal frameworks cannot hold Israel accountable, there are other ways. The fact that Israel also depends on Palestinian aid gives donors important leverage to put pressure on Israel, and this leverage carries with it political responsibilities. The question that remains is if and how global civil society and enlightened aid actors can compel their own governments to utilize this leverage, including through the proper provision of aid, to hold Israel accountable for respecting Palestinian rights to self-determination and development. It would be irresponsible to simply stop providing aid on the basis that aid is being perverted; what is needed instead is a thoughtful conversation among Palestinians, donors, and other aid actors to develop effective, rights-based policy options.

Notes:

Association of International Development Agencies, (June 2011), Restricting Aid: The Challenges of Delivering Assistance in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, available at: http://www.aidajerusalem.squarespace.com/restricting-aid.

Magdelena Sepulveda Carmona, (22 Jan 2009), “The obligations of ‘international assistance and cooperation’ under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,” The International Journal of Human Rights, 13:1, 86-109.

Deborah Casalin, (2015), “Aid Destruction: An Obvious Accountability Issue?” Aid Watch Palestine, http://www.aidwatch.ps/blog/aid-destruction-accountability.

Shir Hever, (2015), How Much International Aid to Palestinians Ends Up in the Israeli Economy? With legal commentary by Richard Falk, Aid Watch Palestine, available at: http://www.aidwatch.ps.

Mohanad Berekdar, Director

Aid Watch Palestine