Natural resources are a crucial element of the economic growth and industrial development of any country. Gas and oil resources, and particularly their derivatives, are most important for economic development, impacting, as base commodities, all sectors of the economy. Accordingly, energy security – created by developing independent natural resources and diversifying the sources of energy to ensure stability of supply – constitutes a pillar of national security.

Permanent sovereignty over natural resources is enshrined under customary international law which guarantees the right of the Palestinian people over their natural resources in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, as clearly stated in numerous UN resolutions.i This right permits the Palestinian people to freely use, control, and utilize their natural resources and correspondingly prohibits Israel, as an occupier under the laws of belligerent occupation, from exploiting the occupied territory or its natural resources in order to advance its economic interests. Israel has been controlling Palestinian natural resources and their development since 1967 as part of its occupation of the Palestinian territory and through policies aimed at entrenching the dependence of the Palestinian economy on Israel. The net result of these policies is that Palestine is completely dependent on imports, almost exclusively from Israel, to meet its energy demands for both domestic and industrial use. The annual cost to the Palestinian economy of importing oil products exceeds US$ 1.5 billion. Israel also controls the volume, price, and delivery of energy products imported to Palestine, which in numerous cases has resulted in disruptions of supply – as evident in the prolonged powers cuts in the besieged Gaza Strip and elsewhere – and in energy prices that are among the highest in the world, burdening the ailing Palestinian economy with enormous financial expenditures that hinder economic development.

The little geological data currently available suggest that Palestine is not wealthy in natural oil or gas resources. However, the scarcity in the availability of these resources is Israeli-induced, rather than wholly natural, and largely the result of Israel prohibiting access, exploration, and exploitation of natural resources onshore and offshore in Palestine’s maritime zones.

To date, there have been very few discoveries of oil and gas resources in Palestine. Nevertheless, there is an indication of potential additional discoveries, provided that effective exploration is guaranteed. The existing reserves discovered so far are crucial not only because they meet Palestinian demand in the short to medium term, but also because they could fuel economic development and growth. However, almost sixteen years after the discovery of gas fields off the coast of Gaza and six years after the discovery of an oil field in Israel that straddles the border with Palestine, internationally-backed efforts to develop these resources remain stalled.

Gas Resources

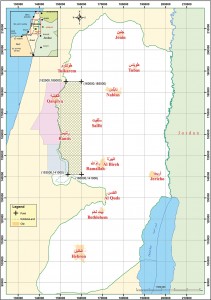

In 1999, the Palestinian government granted an exploration and development license to a consortium led by the British Gas Group (BG Group) that includes the Consolidated Contractors Company (CCC) and the Palestine Investment Fund (PIF) as partners. The license covers a wide area off the shore of Gaza. Geological studies and two exploration wells, drilled in deep water, led to the discovery of two main gas fields within Palestine’s maritime zones. Gaza Marine, the main field, is located 603 m below sea level, fifteen miles west of Gaza. The second, smaller field, the “Border Field” may straddle the international maritime boundary that separates Palestinian maritime zones from those of Israel, a boundary that is yet to be determined. The reserves in the two wells are estimated to be 1.4 trillion cubic feet (TCF), with a production capacity of 1.5 billion cubic meters annually for twenty years and a market value ranging from six to eight billion dollars. These fields are small in comparison to discoveries made by Israel – such as the Tamar field that holds 10 TCF, the Leviathan field that holds 22 TCF – and recently by Egypt, with the Zohr field, the largest ever in the Mediterranean, at 30 TCF.

Despite their relatively small size, development studies undertaken by the BG Group concluded that the Palestinian fields are technically and economically feasible and would suffice to meet Palestinian needs for almost twenty years. Once developed, these gas fields would fuel three power plants. The first is the existing Gaza power plant, constructed to operate on natural gas with a capacity of 140 MW and currently considered for a capacity expansion to 280 MW. At this time, however, it is powered by expensive fuel and operates in limited capacity, producing only 60 MW due to its partial destruction by Israel during its aggression on Gaza in 2014. Two additional power plants are planned, in the north and south of the West Bank, to operate on natural gas: the first in the Jenin area with a capacity to generate 400 MW, and the second in the Hebron area with a capacity ranging from 200-400 MW. In total, these three power plants can generate a maximum capacity of 1080 MW, which meets most of the present consumption in the West Bank and Gaza, estimated at 860 MW and 350 MW respectively. This estimate does not account, however, for growth in electricity demand in Palestine, which is expected to reach 2400 MW in 2025, thus leaving a gap that has to be filled through expansion of capacity, additional power plants, or other energy sources such as renewable energy.

The development of these gas fields is expected to bring enormous benefits to the Palestinian economy. It will directly contribute hundreds of millions of dollars in proceeds to the state in form of royalties and taxes, in addition to profits from the state’s participating interest in the project through PIF, the sovereign wealth fund of Palestine. Furthermore, it will put Palestine on the path to self-sufficiency in electricity generation by providing a relative degree of energy independence. Indirect benefits include job creation, industrial development, and over US$8 billion in savings to the economy in energy expenditure over twenty years, which will come as a result of the relatively low cost of producing energy from natural gas compared to the high cost of importing electricity from Israel.

Yet, beyond the Israeli-imposed obstacles on accessing Palestine’s maritime zones and developing the gas field, its commercialization is challenging. Development costs are estimated at US$ 800 million, and any financial commitment towards that end is dependent on securing bulk buyer(s) of gas willing and committed to conclude a long-term gas-purchase agreement at market value. Such bulk buyers would have to be credit-worthy. In the case of power plants, this necessitates predictability and certainty of cash flow from the effective collection of electricity bills by electricity distribution companies. A last hurdle towards commercialization is the transportation of the gas to its final destination, be it the Palestinian market in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank or a foreign market, as it will require the development of a gas network.

Despite these challenges, the consortium has been working tirelessly in exploring options for the commercialization of these gas reserves. Recently, letters of intent have been signed with Jordan and the Palestinian Power Generation Company that will be building the power plant in the north of the West Bank. These letters are a prelude to the conclusion of gas purchase agreements from Gaza Marine, which will hopefully enable the development of the field. In parallel, plans are underway for the development of the electricity-generating capacity of Palestine, as mentioned above, and for a network for the supply of natural gas, in addition to government measures to reform the electricity sector to ensure its viable commercialization.

The discovery of the gas fields offshore Gaza, along major gas discoveries made in the last decade in the Eastern Mediterranean, indicate the potential for further discoveries. Indeed, the U.S. Geological Survey found in a study published in March 2010 that unexplored potential reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea contain up to 122 TCF of recoverable natural gas, which may include gas fields in maritime areas Palestine claims as its own. Under international law, every coastal state is entitled to an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), extending up to 200 nautical miles from the baseline, within which the coastal state enjoys the exclusive rights for the exploration and exploitation of natural resources. These rights are guaranteed under international law and by the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which Palestine has recently acceded to,simultaneously issuing a declaration determining the full extent of its maritime zones in accordance with the above mentioned convention.

Oil resources

Recent years have witnessed clear indications for the existence of commercial quantities of oil in Palestine. Israel has been extracting commercial quantities of oil from the Meged 5 well since 2011. The size of the Meged oil field appears to be about 180 square kilometers. The drill is located about 150 m west of the 1967 border and about 1.5 km west of the Palestinian town of Rantis. The production capacity of that well is estimated at 800 barrels of oil daily. Seismic studies carried out on Meged 5 indicated that the oil field straddles the 1967 border between Israel and Palestine. It is estimated that 60% of the geological structure of the field is located inside Palestine and that the field includes oil reserves ranging from 30-180 million barrels.

Thus, the Rantis oil project is expected to yield significant benefits to the Palestinian economy. Revenues for the state from the project in the form of taxes, royalties, bonuses, and production sharing range from 60-70% of the project’s revenues and are estimated at US$ 1.3 billion. The development of the project will contribute to energy independence through self-reliance on indigenous resources, assert sovereignty of Palestine over its natural resources, and create an important precedent for the exploitation of other natural resources in Palestine, such as Dead Sea minerals.

In order to develop this field, the Palestinian government has carried out studies which concluded that the field’s development is technically and economically feasible. Accordingly, the government issued a public tender and a model production-sharing agreement in 2013, and again in 2014, with the aim of attracting international and local bidders. Unfortunately, due to the high political risks involved, only one offer was received which did not meet the technical or financial conditions of the tender. The government is currently in the process of considering and deciding on a different path, centered on the establishing of a PIF-led national consortium and on attracting international operators, as a way to ensure the development of the field.

The project’s development is considered challenging and commercially risky due to Israel’s occupation and control of Palestinian territory and of access to land and resources. The concession area for the project spans an area of 432 square kilometers, ranging from north of Qalqilya city to the west of Ramallah, which corresponds to the estimated size of the field per initial seismic studies. The majority of this area is classified as Area C under the 1995 Interim Agreement. Area C should have been transferred to Palestinian control and jurisdiction, along with the powers and responsibilities regarding exploration and production of oil and gas, by the year 1997,ii however, as a result of Israel’s flagrant violations of the interim agreements, it remains under direct Israeli control. Furthermore, as the field appears to straddle the 1967 border, it may be considered as a “joint geological structure” requiring Israeli and Palestinian cooperation as per the interim agreementsiii that Israel violated when it acted unilaterally to license and approve production from the Israeli side.

Conclusion

The Palestinian oil and natural gas resources that have been discovered so far offer promising prospects for Palestinian economic development and for replacing with self-reliance the current Palestinian high dependency on the import of energy products from Israel – conditions which carry strategic implications for Palestinian energy security. The development of these resources is not only a right enshrined under international law, it also constitutes a pillar of independence because it holds the promise of a turning point for the Palestinian economy as a whole; it will impact various sectors by propelling expedited economic growth and creating thousands of employment opportunities, thus facilitating the economic viability and sustainability of an independent Palestinian state. Consequently, the development of these resources warrants the full backing of the international community and the implementation of concrete measures aimed at ensuring that Israel provides the environment required, in compliance with its obligations under international law, to allow the development of these resources to the benefit of the Palestinian people.

» Dr. Mohammad Mustafa is Chairman of the Palestine Investment Fund and the founder of several Palestinian leading companies in key sectors of the Palestinian economy. Previously, he served as Deputy Prime Minster of Palestine and Minster of National Economy, and he held several senior positions in the World Bank on private sector and infrastructure development.

i Among others, UNGA resolution 3005 (XXVII) of 1972; UNGA resolution 3175 (XXVIII) of 1973; UNGA Resolution 3336 (XXIX) of 1974; UNGA resolution 3516 (XXX) of 1975; UNGA resolution 36/173 of 1981; UNGA resolution 37/135 of 1982; UNGA resolution 36/201 of 2009; UNGA resolution 64/185 of 2009; UNGA resolution 66/225 of 2011.

ii Article 15(1)(b) of Appendix 1 to Annex III of the Israel-PLO Interim Agreement on the West Bank and Gaza Strip of 1995.

iii Article 15(4)(b) of Appendix 1 to Annex III of the 1995 Interim Agreement