My grandfather’s name is Mohammad Mansour. In our small village, Biddu, northwest of Jerusalem, he is known as “The Old Man.” He got this nickname back when he was a teenager, because he was so strong, ambitious, and devoted to the land. Seedu i Mohammad was a young man who understood the meaning of land and was especially attached to olive trees. Nowadays, he owns large tracts of land and continues to spend every waking moment tending to his olive trees and preparing them for the big harvest in early October. Typical of most Palestinian families, ours includes 11 aunts and uncles. We are a big family. Every year, we gather and head to Seedu’s land to help him pick olives. Our mothers force us into old jeans and not-so-flattering shirts. We put on our oldest caps that my mom hid in the attic after last year’s harvest, and we bring along water bottles, zeit o’za’atar, tea, and yogurt to cool us down. We always start off energetically but soon begin our childish attempts to escape and annoy the poor donkey.

For some of us it was a 20-day period of hard labor; for others it was an extended outing; but for Seedu it was his life. If Seedu had had the chance to write a CV, his profession would be listed as: Olive Tree Caregiver.

For some of us it was a 20-day period of hard labor; for others it was an extended outing; but for Seedu it was his life. If Seedu had had the chance to write a CV, his profession would be listed as: Olive Tree Caregiver.

There are thousands like Seedu, though I doubt anyone has his strong storytelling skills. Now at close to 90, his job continues to be growing his trees, cultivating them, and finally pressing the olives to get the precious olive oil, more precious than gold itself. He gives each of his children two or three yellow cans filled with the oil and sells the rest to live off the money with Situ.ii This may not seem to fall under the definition of profession as we know it, but harvesting olives is a main source of income for around 80,000 Palestinian families. In fact, according to the United Nation’s 2012 report,iii around 48 percent of the agricultural land in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip is planted with olive trees. This profession not only serves the family that grows the trees, but it also supports other professions.

♦ They are not just like any other trees; they are symbolic of Palestinians’ attachment to their land. Because they are drought-resistant and grow even under poor soil conditions, they represent Palestinian resistance and resilience. Some families have olive trees that have been passed down for generations. The harvest season bears a socio-cultural meaning: families come together to harvest olive trees and realize that their forefathers and mothers had tended the same trees for generations before them.

The Palestinian Initiative for the Promotion of Global Dialogue and Democracy, MIFTAH, claims that “Olive trees account for 70 percent of fruit production in Palestine and contribute around 14 percent to the Palestinian economy.” Although 93 percent of the olive harvest is used for olive oil production, Palestinians use the rest to produce olive soap, known as Saboun Nabulsi,iv black and green olive pickles, and olive-wood carvings. One could say that the olive business is the economic godfather for the Palestinian economy, so my grandfather can rightfully claim that his profession is olive-tree caregiver, except that he can’t because for him to take care of his olive trees he actually has to have access to his land, a privilege rarely granted. Seedu’s beautiful olive trees and large tracts of land, where we grew up picking olives or at least pretending to as children, now stand behind a towering wall; it is becoming harder for my grandfather to access his land. The separation wall stretches over 700 kilometers (430 miles) across the West Bank and separates thousands of Palestinians, like Seedu, from their olive trees. To add insult to injury, 60 percent of the West Bank is considered Area C, which is under full Israeli control. Thousands of farmers are caged into Area A or, if they live in Area C like my grandfather, are separated from their land by a wall, which means that they must obtain special permits to access their land and take care of it. Before Israel constructed the wall on false security claims, I used to see Seedu on the back of his donkey passing in front of our house near his land every day at 7 in the morning. It took him less than 10 minutes to get there, but now he needs to wait behind a metal gate for Israeli soldiers in their twenties or even teens to give him permission to do what he had done uninterruptedly for the past 80 years of his life: tend to his precious olives.

During the last olive harvest, my aunts and mother were denied entry to the land after having to take a long detour through Beit Iksa, a village three kilometers from Biddu. Last year, my younger uncle decided to rent a machine to cultivate the trees because we couldn’t help Seedu. With that, our olive harvesting days as a family ended.

During the last olive harvest, my aunts and mother were denied entry to the land after having to take a long detour through Beit Iksa, a village three kilometers from Biddu. Last year, my younger uncle decided to rent a machine to cultivate the trees because we couldn’t help Seedu. With that, our olive harvesting days as a family ended.

When Israel built the wall, it not only restricted access and movement, it also took over land and destroyed trees to build the wall and pave roads for settlers to use as they commute within Palestinian land. I remember when Seedu was informed that the wall would separate his house from his land. He couldn’t grasp the idea that he would not be able to go there again. He had no words to express his sorrow; we were immensely worried about him. He tried to protest his land confiscation by going to an Israeli court, but that did not bring any results. We consider ourselves lucky that no trees were uprooted, and Seedu’s land wasn’t razed.

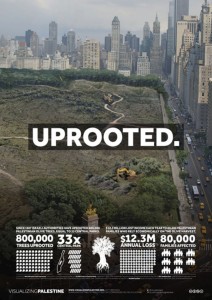

When professions die, it is usually because humans advance and with them their lives change and become more developed. In Palestine, however, olive harvesting is experiencing a dramatic change, but for all the wrong reasons. Mona Chalabi of The Guardian reported that Israel’s reach in the Palestinian Territories allows it to exert enormous power over Palestinian livelihoods. Oxfam estimates that Israeli authorities have uprooted 800,000 olive trees since 1967, resulting in a $12.3 million loss per year. To make the image clearer, Visualizing Palestine chose to express this number through a brilliant infographic, which accurately describes the severity of the situation. The 800,000 uprooted olive trees since 1967 are equal to razing all the 24,000 trees in New York’s Central Park 33 times. I have been to Central Park, and it took me more than half a day on foot to cross half of it.

Palestinian families face growing economic hardship due to Israeli land confiscations, access restrictions, settler attacks, and the widespread uprooting, destruction, and theft of olive trees themselves. In the last week of March alone, the Palestinian owners of a plot of land in A-Shuyukh Village, in Hebron, on which 1,200 olive saplings were planted, discovered that 1,100 saplings had been stolen, and the other 100 uprooted and broken. The owners said that Jewish settlers, from the illegal settlement of Asfar and the outpost of Pnei Kedem, north of Hebron, were behind the assault. As minor as it would seem to the uninformed individual, this incident instantly affects the livelihood of 20 Palestinian families. On New Year’s Eve, settlers uprooted more than 5,000 olive-tree saplings in agricultural lands east of the town of Turmusayya, north of Ramallah. OCHA reported that since the beginning of 2015, 8,202 trees and saplings were destroyed; this is 87 percent of the total number of trees uprooted across the West Bank during 2014.

Palestinian families face growing economic hardship due to Israeli land confiscations, access restrictions, settler attacks, and the widespread uprooting, destruction, and theft of olive trees themselves. In the last week of March alone, the Palestinian owners of a plot of land in A-Shuyukh Village, in Hebron, on which 1,200 olive saplings were planted, discovered that 1,100 saplings had been stolen, and the other 100 uprooted and broken. The owners said that Jewish settlers, from the illegal settlement of Asfar and the outpost of Pnei Kedem, north of Hebron, were behind the assault. As minor as it would seem to the uninformed individual, this incident instantly affects the livelihood of 20 Palestinian families. On New Year’s Eve, settlers uprooted more than 5,000 olive-tree saplings in agricultural lands east of the town of Turmusayya, north of Ramallah. OCHA reported that since the beginning of 2015, 8,202 trees and saplings were destroyed; this is 87 percent of the total number of trees uprooted across the West Bank during 2014.

The present looks grim, but the future is simply frightening. Seedu’s profession and passion might be in no danger for now, but one cannot just ignore the dormant illegal settlements of Giv’at Ze’ev and Giv’at Hadasha across the hill. Seedu might not live to see Israel take over his land, but he still fears that moment. We all know that we are in for a big battle one day. Should Israel persist with its systematic and grave violations against Palestinians, their land, and trees, my grandfather’s workplace, sanctuary, and passion will probably become the forgotten infrastructure of yet another highway or shopping mall, and olive harvesting will be just a blurry memory for Palestine’s future generations.

The present looks grim, but the future is simply frightening. Seedu’s profession and passion might be in no danger for now, but one cannot just ignore the dormant illegal settlements of Giv’at Ze’ev and Giv’at Hadasha across the hill. Seedu might not live to see Israel take over his land, but he still fears that moment. We all know that we are in for a big battle one day. Should Israel persist with its systematic and grave violations against Palestinians, their land, and trees, my grandfather’s workplace, sanctuary, and passion will probably become the forgotten infrastructure of yet another highway or shopping mall, and olive harvesting will be just a blurry memory for Palestine’s future generations.

» Malak Hasan is a Palestinian journalist and amateur photographer who lives minutes away from Jerusalem. She holds a master’s degree in communication and public relations from the United Kingdom and is currently in charge of the English page of the Palestine News Agency WAFA. You can follow her on Twitter: @MalakHsn.

Article photos courtesy of Malak Hasan.

i “Grandfather” in some Arabic city dialects is also pronounced “Seedi” in the villages.

ii “Grandmother” in some Arabic city dialects is also pronounced “Siti” in the villages.

iii http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ocha_opt_olive_harvest_factsheet_october_2012_english_0.pdf.

iv A type of castile soap produced in Nablus in the West Bank, Palestine. It is made of virgin olive oil (the main agricultural product of the region), water, and an alkaline sodium compound.