One dot, two dots, three, four, five, six, seven, and eight. “Do you know their meaning, what they stand for?” he asked. “My grandmother had them,” I replied. The symbol is eight dots closely drawn to one another. My sister and I are looking at each other and mumbling. We have the drawing; we are measuring the dimensions to the sizes of our fists. Half an hour or so passed with the artist pinpointing the location. Not too close to the wrist, not as far down as the finger, beneath the center and equally spread, he traced the ink on the back of my hand, the right one. The first time didn’t quite work. “A little lower please,” I requested. He erased the ink and retraced the shape. “Yes, right there…” One dot, two dots, three, four, five, six, seven, and eight. He gently punctured the skin.

My grandmother, the mother of my father, passed away in the summer of 2008; may her soul rest in peace. Eight dots delicately appeared every time she grinned, her eyes reflected hazel green, and so did her hand. After our session, we drove home giggling and smiling. Our Monday became ultra spectacular! For an entire week, I hid my fist from my mother. She was not happy with my choice per se; however, she was not utterly surprised either. From the drawer of her cabinet, I drew my grandmother’s picture, taken by the same sister, our photographer, on another memorable day.

On Friday afternoon, April 18, 2014, my friend drove my brother and me to Haifa. The ride, smooth as the breeze, took less than three hours. Eyes yearn to see fire seep through water and waves move with the wind. The trip coincided with the annual Easter celebration on April 21, which we commemorated in Iqrit (اقرت), a village north of Nazareth. We travelled exactly 25.5 kilometers from Acre (عكا) to arrive in time for the festival. Honored with arts and crafts, four generations of children – daughters and sons, mothers and fathers, grandparents, uncles and aunts – sang, prayed, and gave thanks. On top of the hill, an old woman with her family. I sat next to them.

“Washm?” (tattoo) she sparked the conversation. I nodded, then explained my adventure with my sister. “Yes, back in my day, women got ink embellishments all the time. Some of our women had their entire faces covered in various designs and illustrations,” she spoke softly. “Brides often got them on their wedding day. Flowers were common on the face, and different types of lines covered the forehead.” Her husband beside us painted the monument of St. Mary’s Church. “Al-Deriyyat (الديريات) used to go around and print them. Daq (دق), they called it. They used metal, wood, and fire.”

A fervent beaming sun reflected powerful blue and yellow hues. “They used daq for medicinal reasons,” she continued. “When somebody felt pain, they treated the person with daq. Sometimes pain is psychological. When a person ached or felt bad, they applied daq on the ear or the hands, on different places, depending on where the pain was coming from. Then the pain went away! Islam forbids al-washm though, considers it haram! Al-washm is permanent, you know. It changes the skin permanently! The skin is a part of our body, and Islam forbids changing the natural appearance of our body.”

Our conversation carried on. She told me about Tiberia, her days there and the village they now live in. “We are from Tiberia, but the Israelis kicked us out in 1948. And now we live in a village nearby,” she explained. The yellow and blue now turned grey. Fine flickers of salt mixed in the air. Her husband packed the canvas waiting to be completed. “Al-amaneh, come see us there some time,” she said, and then waved goodbye, moments before sunset.

**

Now in the East Bay of California, far west of the continent of her birth, my grandmother doesn’t seem so distant. Whether alive or dead, a piece of me resembles her – her eyes, her smile, and her face – through invisible lines and eight dots of ink.

“The relationship between the person who receives the tattoo and the artist is very intimate. I got my first tattoo when I was fifteen.” The only person I knew who practiced the old tradition spoke to me about her experience. “My friend and I were in the desert in Slab City, California. We had spent a whole month fasting and meditating. Then we got the idea! I started poking my skin right before sunset. For a while, I was drawing those two dots with makeup. Then I knew it was time. Poking myself felt very uncomfortable. So my friend finished them for me.” A dot of ink printed beneath each of her eyes. “When I looked at my friend, I knew exactly where I was going to pin hers. Bonding new energy! I was in love with pinning each dot! The magic amused me. I’ve always been interested in magic,” she continued. “The energy things carry and figuring out how to discover it.” A new perspective on magic intrigued me. “Now, it’s artsy to get tattoos, but there is an ancient practice behind them. Women and warriors used them for protection,” she explained. I wanted to know about the tools she used. Were they the same as the ones they traditionally used? “The tools I use? Here, I’ll show you….” She pulled out small needles from her bag. “See … here, look. This one has three small heads; this has one; some come in a line; I used to have them but I’ve run out! When I first started though, I used a pencil, a sewing needle, and thread.”

We sat in the sunlight of the vast wide sky. The weather in Oakland is not too cold and not too hot. “Both methods – the modern and the old – have openness and healing aspects. They have a different finish though. Modern tattoos are very clean and tight, usually they appear black! The tattoos I make are rougher, and the color depends on what’s in the ash, it can vary. I prefer the ancient method of poking the skin open and sealing the wound with the ash. The color fades while the wound heals. “Open a wound and dust it off! Let the ash seal and heal the wound! Fire, smoke, air, and prayer. The energy carried is very powerful. In flames is best!” Her words echoed.

On a Sunday evening, I watched with curiosity the work of an artist as she printed her design on the calf of a girl, a woman. “I have eight tattoos,” she said, “this is my ninth! And it is the first sci-fi-like figure I’ve gotten.” The drawing of a female figure with octopus arms and legs, splurting waves through her mouth was gradually engraved underneath her skin, intensely, but with care. “She strikes me as Octavia!” I said. “Octavia Butler is my favorite sci-fi author!” she responded. Her expression remained calm and relatively casual, while the artist performed her art.

A few weeks later, I entered the same tattoo shop and talked to one of the artists. “How did you become involved in tattoo art?” I asked.

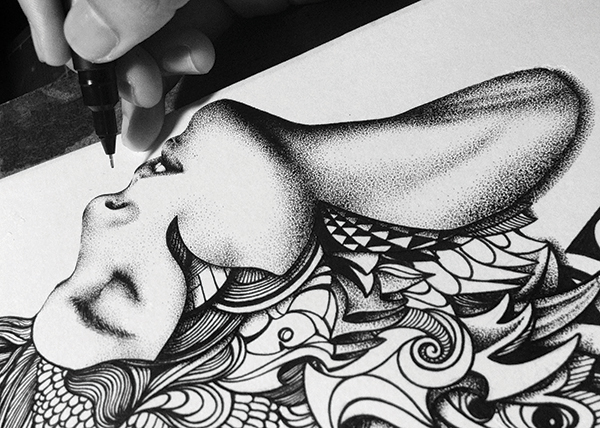

“I started drawing and painting when I was very young. Then I got into sculpting and 3D-design. Through a friend of mine, I began hanging around tattoo shops, and from there, I was offered an apprenticeship. Typically, an apprenticeship takes one to three years, and it is the standard process for artists to begin practicing tattoo art,” he answered.

“In the United States tattooing became really popular after television shows such as Miami Ink.” The conversation continued. “Prior to that, tattoos were associated with punk rockers and bikers,” he explained. “Designs were smaller and not very involved. Nowadays, you see a wide variety of people with full-body tattoos, large compositions, and the entire color spectrum! Working with the human body, one comes up against the limitations of the skin. The ink spreads as the skin ages. So we have to keep the factor of time in mind. The ink goes beneath the surface in a tattoo and the skin is curved, so these are further challenges that the tattoo artist must consider. The work is tight, clean, and planned-out!”

“Before receiving a tattoo, the client signs a waiver. Further,” he elaborated, “we provide after-care instructions and keep to a high standard of cleanliness. The level of hygiene we abide by is the same as in US hospitals.”

“Have you experienced somebody reacting badly to a tattoo you’ve created?” I asked.

“Yes, I had an experience whereby the client reacted badly to the ink after the tattoo was done. I got rid of all my equipment! Some pigments, like red for example, contain more reactive material.”

“How come?” I wondered.

“Red for some reason contains a highly reactive substance,” he explained. “Most of the time, reactions happen due to lack of care after the person gets the tattoo, exposing the skin before it heals completely, or not providing proper care.”

The Waiver, Release, and Consent to Tattoo and\or Piercing Form clearly states:

I acknowledge that a tattoo\piercing will result in a permanent change to my appearance and that a tattoo can only be removed by laser or surgical means, which can be disfiguring and\or costly and which in all likelihood will not result in the restoration of my skin to its exact appearance before being tattooed.

**

matter of matter

mattering matters

matter is the matter

form

dots

8

888

888

8

dots

form

8

888

888

8

ink

**

“Tribal beliefs from older generations use marks as a sign of status. In the Philippines a few Kalinga live in the north. The divided country, with Christian Catholics in the north and Muslims in the south, faces conflict.” I remembered watching the video, Fang Od and Kalinga Tattooing in the Philippines. We talked about the video. Then he continued, “Python skin, drawn in hexagons, wards off the evil eye.” The lines cover his entire right arm. “A woman obtains her first tattoo when she gets married. The prints depend on the status of the husband,” he said smiling. “The event is ceremonial and very spiritual.” I imagined a bride on her wedding day, her feet being pinned.

“Men earned their tattoos,” he emphasized. “The centipede for men attested fierceness and courage. Solemn triangular shapes sealed the wrist of warriors, after successful headhunting. For women, the lines slowed down aging,” he added. I imagined a bride on her wedding day having her cheek embroidered. “Traditional tattooing takes twice the time, and causes more pain. Lemon thorn was commonly used for drawing and picking skin. To make ink, they scraped residue from the bottom of cooking pots.”

“Different tribes used various types, lines, drawings for different reasons,” he went on. “The Mentawai tribe in Malaysia, for example, were tattooed so that their ancestors would recognize them, and to keep their souls from wandering from the body. The Iban tribe tattooed down the neck to prevent certain diseases such as arthritis and rheumatism. Women also tattooed beauty marks, and used their signs to scare the enemy away. The God of Rice meant beauty.”

**

Dear Grandma,

Your hazel eyes in my memory, clear as though you were standing in front me; seated in the garden of Uncle Ismail, shaking something in the gut of a sheep. “Child, come here,” your voice sounded. “Try the magic I just created!” From your hands, a strong taste melted in my mouth, sweet, like your smile. You placed your right palm on your lips, held your white mandeel and eight dots appeared, faded green.

**

♦ Dear Grandma, Your hazel eyes in my memory, clear as though you were standing in front me; seated in the garden of Uncle Ismail, shaking something in the gut of a sheep. “Child, come here,” your voice sounded. “Try the magic I just created!” From your hands, a strong taste melted in my mouth, sweet, like your smile. You placed your right palm on your lips, held your white mandeel, and eight dots appeared, faded green.

“Now that you’ve got a tattoo, I’m thinking about getting one!” I recalled my friend saying.

“What would you get?” my sister asked her.

“Al-sayyaleh,” she answered.

“You would look good with al- sayyaleh!” I told her.

Al-sayyaleh is an ink line that starts from the midpoint of the lip and streams down to the midpoint of the chin. Some extend the design farther and elaborate the line with more complex figures. They stretch as far down as the neck. Blue circles on the hands, the tip of the nose, and above the eyebrows were very common. Combined with equilateral triangles on each cheek, it makes Hijab Wharf Alzban. The feet opened 4 cm long in rectangular-shaped lines, with a dot at the bottom of the heel, called daq al-qifl (lock ring). Each woman enjoyed unique shapes, lines, and figures. No two tattoos were the same.

Thanks to the strangers, friends, and professionals who offered time to speak to me about their knowledge and art.

**

» Manar A. Harb is a contributor to This Week in Palestine.