Even for me, an Armenian, it feels a tad incongruous that I am writing about the horrors of the Armenian genocide that occurred 100 dusty years ago when much of the world in 2015 is wrestling with so many more contemporary pressing concerns. From ethnic cleansing to religious persecution, from the murderous excesses of groups such as Daesh/ISIL or Boko Haram to the political violence rending the MENA region asunder, do I truly need to raise this human rights issue on the magazine pages of This Week in Palestine today? Surely I should focus on the present rather than dredge up a case that purportedly belongs to the annals of history?

I cannot do that. Nor should I for that matter! Why?

I grew up in Ramallah and I remember as a boy sitting on my maternal grandfather’s lap and listening with rapt attention to his stories about the atrocious way in which members of his family – my family – were killed, maimed, abducted, or deported to the Syrian Desert by Ottoman Turkey under the cover of World War I. He would talk to me about his grief and recall how his family had to flee to Lebanon and then go to Palestine in order to re-build their lives. Paradoxically, my maternal grandmother never recounted her experiences as a young lass, and I suppose that her way of coping with the pain and angst was simply to keep mum and hope that “out of sight” would somehow morph into “out of mind” too.

I remember once asking my grandfather why he brought up this chapter of Armenian suffering with unerring frequency and why he shared those memories with me – a kid whose emotional intelligence was at best unkempt – and in the process filled my head with images of blood and gore. After all, here was a man who had reassembled his fortunes twice in one lifetime (once after the genocide and again in 1948 when he was forced to abandon his home and business in Talbieh) and was now both successful and rich. Surely it would have been better to move beyond this painful threshold and draw a line under it?

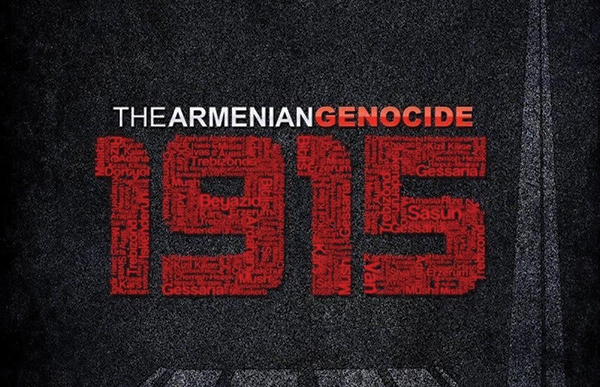

♦ Should we really bother with the Armenian genocide a century on? Or are Armenians simply making much ado about nothing? Written by the grandson of a genocide survivor, this comment mixes the personal with the scientific as it recalls the centenary of a crime that started in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) on April 24, 1915. The writer argues that there can be no closure without recognition and focuses on those various elements that render such a crime relevant to our modern days.

His answer was lucid then and it remains so for me today. My granddad explained that I needed to learn about my family history so that I could then build on it and be proud of our collective achievements as Armenians despite the vagaries of time. But equally importantly, he added, there could be no closure to a genocide that claimed well over one million innocent lives without recognition. I was not too convinced then, but am much more so today, and I can easily extrapolate the Armenians’ yearning for recognition of their catastrophe to that of Palestinians who feel robbed of their rights through the Nakba too.

This year, as 10 million Armenians the world over commemorate the centennial of the genocide, I am not going to rake over old coals simply to prove yet again that this event in the lives of Armenians qualifies as genocide under international law. Lawyers (such as Geoffrey Robertson, QC, in his 2014 book entitled An Inconvenient Genocide), academics (such as Donald Bloxham), and organizations (not least the International Association of Genocide Scholars) have time and again clearly stated that this was genocide. And as prominent scholars of genocide such as Yisrael Charney, Robert J. Lifton, Deborah Lipstadt, Eric Markusen, and Roger Smith have also reminded us, it is important to fathom the immorality and harmful consequences of denying genocide. After all, denial is the final stage of genocide. It seeks to demonize the victims and rehabilitate the perpetrators. It paves the way for future genocides by making it clear that such heinous acts demand no moral accountability or response.

Instead, I will simply share with readers today a few personal convictions about this tragic event in the hope that they will be no more and no less than food for thought … and perhaps for solidarity too.

- When we Armenians speak of the genocide, I believe we forget or even fail at times to show our full gratitude to all the Arab and Muslim men and women in the Middle East who received so many Armenian orphans on their lands and in their hearths. Whether in Palestine itself – and the Armenian Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem is merely an exemplar of that welcoming hospitality – or else in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, and elsewhere, the memorable generosity of those peoples translates into a debt of gratitude by Armenians across the diaspora.

- Nor should we omit mentioning those Turkish “neighbors” in all the provinces of Ottoman Turkey who defied their political leaders and harbored, sheltered, or adopted many Armenian orphans in order to spare them from certain death. Their story is not often told, and we must not forget that such righteous people with their brave deeds are one proof of our collective humanity.

- As an Armenian, I am not too hung up about whether the United States, the United Kingdom, or other countries resolutely refuse to recognize the genocide formally. I know that they are cowed by their fear of upsetting Turkey as a geostrategic partner and so they try to use various euphemisms in order to express their empathy with fellow Armenians. For me, however, the stories I heard from my grandfather and scores of other Armenians are testimony enough to this crime against humanity.

- Having said that, there are two key countries that should recognize this genocide. The first is Turkey itself. Acknowledging the crimes of its predecessor Ottoman Empire would not only free Armenians to pursue closure but it would equally free Turks who are constantly tugged down by accusations about their denial of this crime. The Turkish intelligentsia is gradually opening up to this reality but the political leadership refuses to do so due in part to an overweening sense of nationalism let alone a fear that recognition could open the floodgates for claims of restitution.

- The other key country is Israel. It refuses to recognize the Armenian genocide and plays crass political games over it with Turkey. But how can a people who underwent the horrors of their own Holocaust refuse to recognize the pain of Armenians? Mind you, Holocaust scholars such as Elie Wiesel and Mark Levene have often spoken of this genocide, but politicians cheapen further their own flimsy ethical credibility on this topic by constantly denying recognition and fudging history.

- Finally, I would argue that the Armenian genocide is not a sui generis event that can be viewed on its own merits alone. As the first dastardly act of the twentieth century, it should be viewed inclusively alongside other genocides such as the Holocaust, Cambodia, Bosnia, Rwanda, Darfur, and other ongoing crimes. To expect solidarity from others necessitates reciprocity of word and deed too.

Unlike all previous years, Turkey has this year sadly decided to commemorate the battle of Gallipoli (in which the Ottoman Empire fought against Britain and its allies) on April 24, which marks the symbolic starting date of the Armenian genocide of 1915. The choice of date indubitably has little to do with the battle of Gallipoli per se as it has with an attempt to exterminate the memory of a race. Yet the choice of this date as a way of minimizing world attention to the commemorative events that will take place in the Republic of Armenia demonstrates how the Turkish political establishment rejects the Armenian sense of bereavement and blatantly pursues the trite attitude of an ostrich burying its head in the sand.

One century of denial is a long time. However, as an Armenian website (https://100lives.com/en/) shows quite clearly, one can find glimmers of light even in the darkest hours of human history. As a token of appreciation for those courageous men and women who stepped up to the plate and helped Armenians in their most dire moments, this website is one way of sharing these stories. It represents an attempt to celebrate those generous men and women and to continue their example by supporting people and organizations that keep alive the legacy of truth and fellowship. After all, whilst many people admittedly care about this genocide, how many people care enough to act?

This month, as I recall my grandfather’s words anew, I would also like to remind readers that genocide is ubiquitous in that it tends to repeat itself if it is not tackled by men and women of good will. I will do this simply by quoting Adolf Hitler’s infamous (and ominous) words in August 1939 as his army prepared to attack Poland, “After all, who now remembers the annihilation of the Armenians?”

This month, as I recall my grandfather’s words anew, I would also like to remind readers that genocide is ubiquitous in that it tends to repeat itself if it is not tackled by men and women of good will. I will do this simply by quoting Adolf Hitler’s infamous (and ominous) words in August 1939 as his army prepared to attack Poland, “After all, who now remembers the annihilation of the Armenians?”

» Dr. Harry Hagopian is an international lawyer and MENA regional consultant. He was CEO of Campaign for the Recognition of the Armenian Genocide (CRAG) in London for four years. His writings on the Armenian genocide can also be found on http://www.epektasis.net/Armenia/Armeniaindex.html.