Xenophobia (a compound of ξένος, xenos, “foreign, unusual” and φόβος, phobos, “fear”) is defined in most dictionaries as fear or hatred of strangers/foreigners.

“What is she doing here?” Elena and I have been spending our winters in Jericho for over thirty years. Everyone knows us except for this Palestinian lady at the vegetable market. She pointed her finger at Elena, of French Costa Rican descent, and exclaimed in a loud voice: “No foreigners are allowed in Jericho!” Her denunciation fell on deaf ears. People were polite and ignored her. Ironically, Elena and I were the locals in Jericho and the lady was an outsider buying vegetables. Someone whispered in her ear. She muttered something and left. The moment passed in peace.

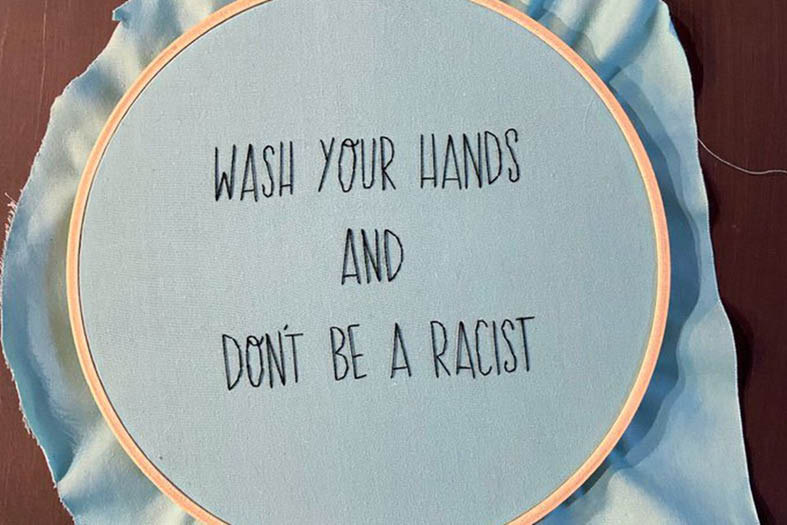

Social stigma, blame, and discrimination have been recurrent phenomena during epidemic outbreaks throughout history. The negative attitude is tied to the fact that people often need to make sense, find a reason, for the outbreak of a contagious disease. Scapegoating by singling out particular communities, ethnic groups, or races is a common strategy of laying the blame on the other.

The outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in December 2019, which was first reported in the city of Wuhan, Hubei, China, has led to increased prejudice, xenophobia, discrimination, violence, and racism against Chinese people and people of East Asian and Southeast Asian descent and appearance not only in Palestine but throughout Europe, the Middle East, and North America. Initially xenophobic attitudes regarding coronavirus focused on specific stereotypes surrounding Chinese people. Unfortunately, social media played a major role in propagating Chinese culture as backwards and its exotic cuisine as unhygienic thus providing the perfect corona incubus. This highly selective, distorted, and often faulty portrayal has led to misperception and, even worse, misinformation about the source and course of the coronavirus. The general panic and collective hysteria and fear of contagion developed into xenophobia and hostile aggression directed towards the Chinese in particular and East Asians in general.

As the whole world is afflicted by an outbreak of the novel coronavirus, Palestinians in Bethlehem and its surroundings were confronted on March 5, 2020 with the fact that tourists, the main source of their livelihoods, could also pose a threat.

As the statistics of the coronavirus epidemic increased, and as it spread from a geographically confined epidemic – crossed borders to become pandemic – the greater the panic and more temptation to blame and fear the outsider: the other. In this mass hysteria and collective panic, the scientific empirical fact that germs and viruses do not operate on the basis of race was overlooked.

The unprecedented first xenophobic hate expression was recorded on March 1, 2020, in Ramallah. A Palestinian mother with her daughter chanted “Corona, corona” to two Japanese women who work in an NGO. The mother then attacked and pulled the hair of one of the Japanese women who attempted to record the incident. The Palestinian woman was arrested later that day. Ramallah Governor Leila Ghannam invited the two Japanese ladies to meet with her to thank them for their relief efforts. A senior police officer gave them flowers during a visit to the nongovernmental organization’s office. Nevertheless, the hate assaults against the Southeast Asians did not subside.

The color of their skin, the slant of the eyes, and their language make East Asians an easy target even though the Asians in Palestine, namely Japanese, Koreans, and Filipinos, have been living among us for years, and therefore pose no risk whatsoever. These factors did not matter: they are of a different race and culture and are therefore foreign. Asians were perceived by the plebeians as the incubus of the coronavirus. Having lived in Japan for a total of almost six years, I was always very well received. The friendships I forged during my extensive travels in Korea and China have, to a large extent, shaped my sense of identity. I feel deeply embarrassed when a few of my fellow Palestinians act negatively towards Asians. “The current prevalent xenophobia,” wrote a Korean expatriate, “has been degrading our basic rights and day-to-day life in Palestine.” A long list of names of Asian expats on an excel spreadsheet aptly reveals the extent and number of incidents of abuse they have had to endure since the advent of corona.

Xenophobia has always been intimately tied to mass panic and hysteria, particularly when it comes to diseases. In cases where everybody is a victim, there is no “convenient other” to blame except the foreigner. This apologetic explanation, however, does not justify the ignorant racist behavior. Palestinians, like all other peoples, are complex human beings. Vulnerable, emotional, they love and hate. But most of all, like everyone else, they are afraid of sickness and ultimately of death. Collective panic undermines traditional humanist values.

Unfortunately, victimizing the other during times of stress and disease, though morally and ethically unacceptable, is common. During an outbreak of H1N1 swine flu in 2009, Mexicans and many Latinos were scapegoated. During the 2014 Ebola outbreak, so were people of African descent. One can even go as far back as the early 1980s when Haitians were blamed for HIV/Aids.

The nightmare with which the sequence of events unfolded jolted and altered the Palestinian consciousness of self and other overnight. As in a Greek tragedy, the Palestinians awoke to the realization that their source of economic boom and comfort, namely tourism, underlies the spread of coronavirus. On Thursday, the fifth of March, Palestinians were jarred by the initial news reports that four European tourists were being held at the Beit Jala governmental hospital infected with the virus. People were initially wary to believe the reports, as gossip and falsehood surrounding the virus reaching Palestine had been circling around social media since early February. The rumors reporting the increasing number of tourists both afflicted with or carriers of COVID-19 alarmed Bethlehemites and alerted them to the fact that tourism and European tourists were dangerous. Sporadic closure of a hotel here and there confirmed the worst fears. Both the minister of tourism, no doubt coerced by the tourist business consortium, and the local politicians tarried in taking action. More tourists were hospitalized, quarantined, and deported while hotel workers who had been in touch with them were put under medical surveillance. In the panic, Palestinians hurled xenophobic, abusive, verbal expressions against Japanese, Korean, and Filipino expatriates. Corona became feared as the foreign disease brought in by tourism.

On the fifth of March, a state of emergency was declared in Bethlehem, one of the major destinations of tourism in the Holy Land. The Palestinian Ministry of Health announced that there were seven confirmed cases inflicted with the coronavirus held in quarantine. Moreover, those affected were confirmed to be local Palestinian hotel workers who had come into contact with a group of Greek tourists. These seven cases were the first confirmed cases of the coronavirus in Palestine.

Alarmed by the new developments, Israeli Defense Minister Naftali Bennett announced on that day, in coordination with the IDF and the Palestinian Authority, a closure of Bethlehem. The Israeli defense ministry said it had imposed emergency measures on Bethlehem, with everybody forbidden from entering or leaving the city. It added that the lockdown had been imposed “in coordination with the Palestinian Authority.”

Late on Thursday evening, Palestinian Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh announced a 30-day lockdown, saying that the measures were essential to contain the disease. All schools and educational facilities would close, he said. The virulent corona epidemic had arrived in Palestine.

Pandemonium broke loose. All public parks and tourist sites would close, while large sporting events, conferences, and other major gatherings were cancelled. Things happened all at once; churches, mosques, hotels, and restaurants were shut down as tourists were rushed out of Bethlehem. The unseemly manner in which the foreign visitors were evicted and the unsightly long line of buses stranded on the highway for lengthy hours as each group waited for its flight home shook the Palestinians as they realized that tourists of various European nationalities were carriers of the virus. Their boom was their hamartia. Xenophobia towards Chinese tourists was generalized to encompass all tourists. For a brief moment, corona became the foreign disease brought by tourists; a myth that was soon to be dissolved when Palestinians learned that coronavirus does not differentiate according to race, culture, religion, or language.

In the world at war against corona, the diversity of human cultures faces the same virus. Humanity at large, men and women of all races, ethnicities, cultures, and languages stand united against the invisible enemy. Imminent and present in Palestine as everywhere on earth, the enemy is the virus itself. Each people conducts the battle in its respective homeland in the war of containment and eventually defeats the virus. Each nation contributes to the war waged against the onslaught of the virus by strategically fencing it in and delimiting its scope of expansion. Danger no longer originates with the foreigner, for each of us runs the risk of being a carrier. The danger does not lurk outside, it may be in the friendly face of the neighbor, the jovial face of the baker, butcher, or grocer, the sweet smile of the mother, and the compassionate caring pat of the father, brother, or husband. The coronavirus lives among us. Each of us is a potential incubus.

As we watch with pity and horror the increasing number of patients in Bethlehem, our sense of compassion deepens. To help out, benefactors from Hebron and other towns donate food and basic necessities in prodigious amounts to Bethlehem. Our sense of altruism deepens, as witnessed in the manner with which villagers, townspeople, and Jerusalemites have come to realize that our moral duty compels us to protect the others from ourselves. In this jihad struggle against the invisible power of nature, we are aware that we should neither allow it to afflict us nor become carriers nor pass it on to others. We stay home.

“Overall, Palestinian families in the West Bank have adapted to the new situation and stay indoors,” my friend Mohammad from Al Ma’sarah told me. “Since the onslaught of the Israeli occupation, we have had to live under siege, closures, and curfews. In fact, we have kept to our homes ever since mid-February when the rumors first started.” After a moment of pensive silence, Mohammad explained, “There are no social visits, and children are kept indoors. Internet keeps everyone in touch. Shopping for necessities is done briskly, and most people have stored food for months…”

The precept of the enemy as the other persists. As many Palestinian families depend for their income on the Israeli labor market, they have no alternative but to go on working inside the Green Line. Whereas Palestinians pride themselves on their sense of discipline and hence the containment of the virus in one region, namely Bethlehem, they view Israelis as nonchalant, easygoing, and lax. The triumph of order versus chaos, Palestinians argue, is evident in the disproportionate increase in number of patients in the Jewish sector. In the polemic over whether Palestinians should stay in the safety of their homes as a health measure, the pragmatic economic imperatives had the final say. Israelis, on their side, limited the number of Palestinian workers to around twenty thousand, without granting them permission to return to their families for two months. The workers would stay in special lodgings provided by the contractors.

Bethlehem remains under quarantine. The stigma of being a coronavirus patient, of being related to one, or of being a positive carrier is unbearable for some. A few go berserk while others panic and, as seen in social media clips, have to be forcibly put in quarantine.

“They walk out in the streets, mingle with people, laugh and joke in total disregard of the consequences of their rash behavior,” my friend Baha’ told me over the phone. “We almost have to beg and plead with them to stay indoors.” He summed up, “the situation is grave, and a curfew must be imposed to control the people.”

At this critical moment, a group of Bethlehemites – much like the chorus in Greek tragedy – formed a line in Manger Square in homage to the Italians. Cultural, historical, and religious affiliations with Italy underlie the gesture. The gesture, an expression of human solidarity with the Italians where the battle with the virus has reaped many victims, was followed by Augusta Victoria Hospital in Jerusalem that floodlit the monumental building atop the Mount of Olives with the colors of the Italian flag.

Yesterday a German friend was walking down Al-Zahra Street in Jerusalem. Three young schoolboys approached her, sneering and chanting, “Corona corona…”

“They were little children…I could not be angry,” she said.

She smiled kindly at them and answered with a heavy German accent,

“Ana baskun bi jabal al zeytun min zaman.” (I have been living on the Mount of Olives for many years.)

The moment they heard her speak Arabic, they were charmed. Their faces relaxed, and they walked off.

It is understandable to be alarmed by the coronavirus. But no amount of fear can excuse prejudice and discrimination against foreigners. Nor is it a stigma. Let’s fight racism, call out hatred, and support each other during this public health emergency. StandUp4HumanRightsandDignity.