The Gaza Strip suffers from an economic crisis and rising unemployment levels. According to the Labour Force Survey conducted by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) in November 2019, the unemployment rate in the Gaza Strip was 45 percent compared to 13 percent in the West Bank, whereas the unemployment rate for males in the State of Palestine was 20 percent compared to 42 percent for females. Thousands of graduates are seeking job opportunities, yet the Palestinian labor market is not capable of providing employment for all of them. Incubators are part of the solution and have been established to contribute by helping innovative youth grow and start their own businesses.

These incubators have implemented several programs and projects in the Gaza Strip related to the promotion of entrepreneurship, incubation, and acceleration in various sectors. Hundreds of start-ups graduated from the incubators, resulting in other youth being employed in these start-ups.

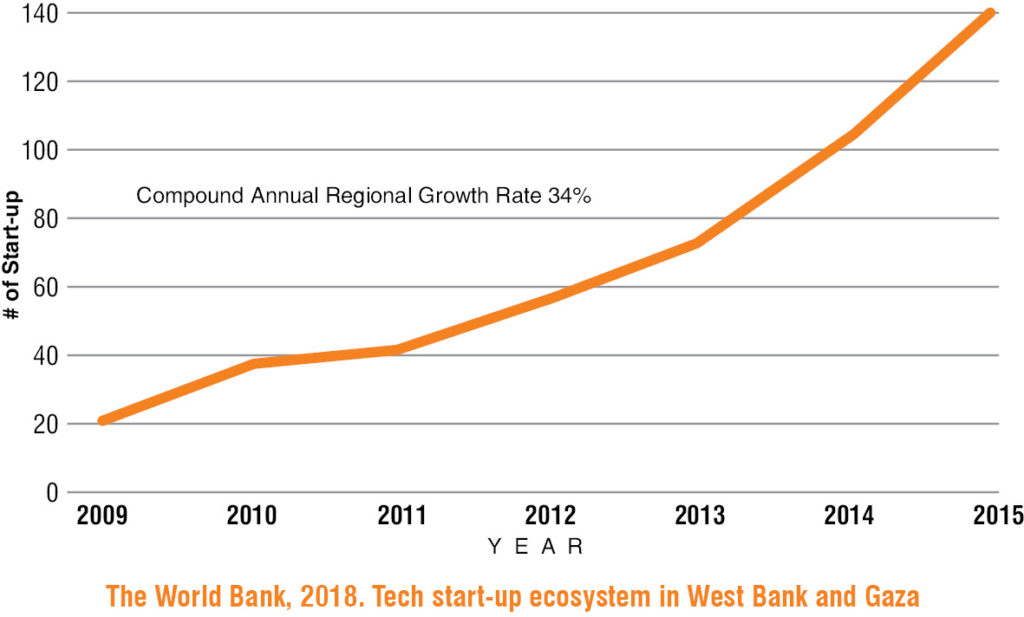

Statistically, entrepreneurship has been rising year after year in the Gaza Strip. On average, there is an annual increase of 19 start-ups, resulting in a 34 percent compounded growth rate in start-up creation since 2009, as indicated in the graph below.

There are many organizations that conduct programs and carry out projects and initiatives to support entrepreneurs in the Strip. One of the pioneering incubators is the Technology Incubator of the University College of Applied Sciences (UCASTI), founded in 2011 as a supportive initiative to help in decreasing the level of unemployment. It has successfully incubated over 100 projects, marketing them for local and regional markets and stakeholders. UCAS Technology Incubator supports entrepreneurs who have creative and ambitious ideas by providing them with administrative, technical, and financial support. The aim is to assist these start-ups in becoming successful businesses in the market.

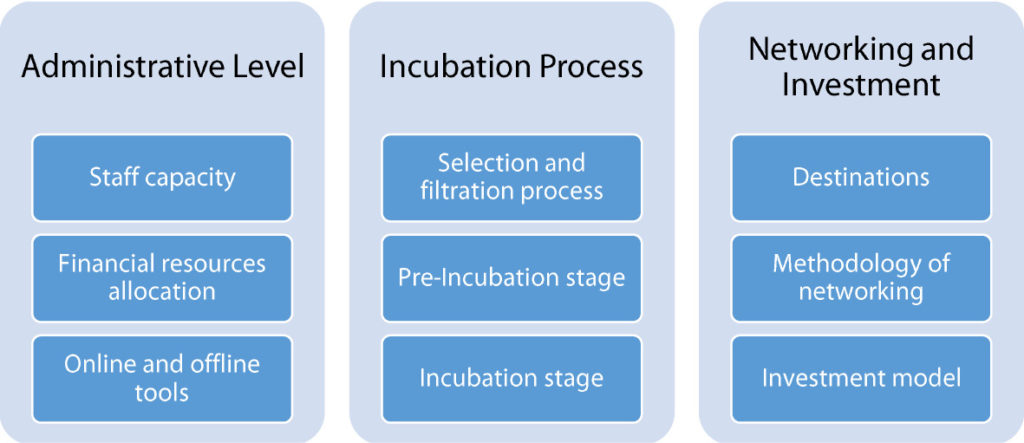

With a fund from the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), UNDP supports Gaza incubators, aiming to improve the applied incubation models and systems. It identifies shortages in the selection process and in the support given to entrepreneurs and proposes action plans that address these gaps. To accomplish this, UNDP has partnered with UCASTI and implemented interventions that enhance the Gaza incubators by improving three main components: the administration level, the incubation process, and networking and investment. Each one of these components entails multiple activities.

To determine an incubator’s success, specific standard criteria can be applied. Each year, several studies rank incubators worldwide, and focus is placed in particular on those that are university-affiliated. One of the best studies regarding incubator ranking is that of UBI Global, founded in 2013 in Stockholm, Sweden, to identify where innovation hubs are located worldwide and to learn and share what makes them successful.

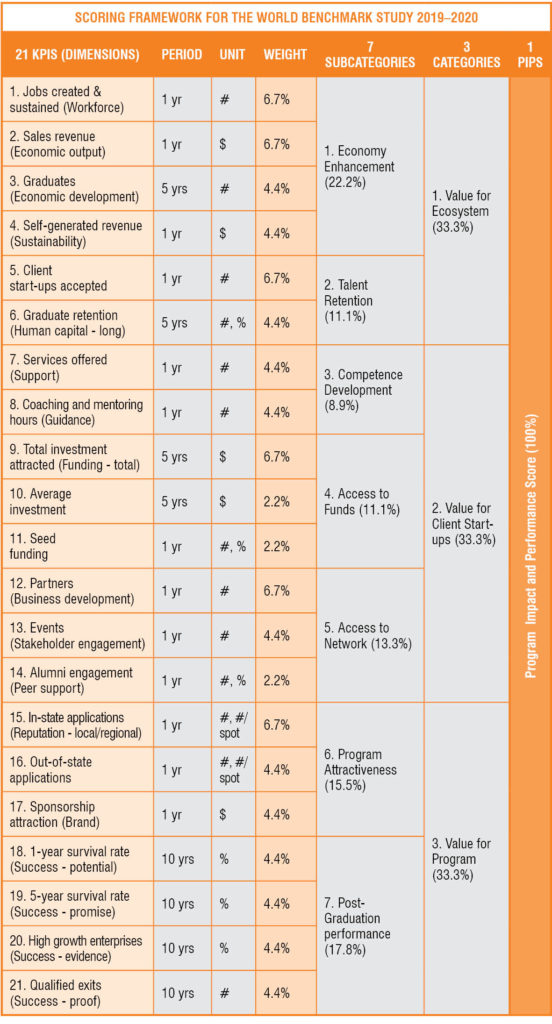

UBI’s report and world ranking of business incubators and accelerators 2019/2020 utilized 21 key performance indicators (KPIs), identified by the relevant research literature. These KPIs form the base of the seven subcategory scores, which in turn form the scores in the following three main categories used to calculate the individual program’s impact and performance scores (PIPS) for all benchmarked incubators and accelerators.

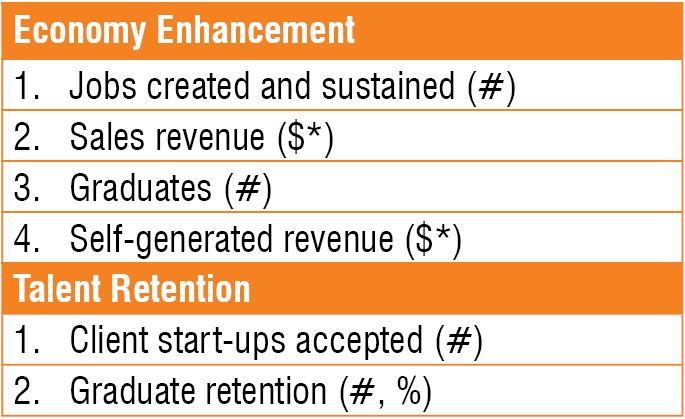

The Value for Ecosystem category assesses the economic impact and performance of a program and its client and alumni start-ups, also considering program success in retaining human capital and start-ups in the ecosystem. The subcategories Economy Enhancement and Talent Retention encompass six identified KPIs.

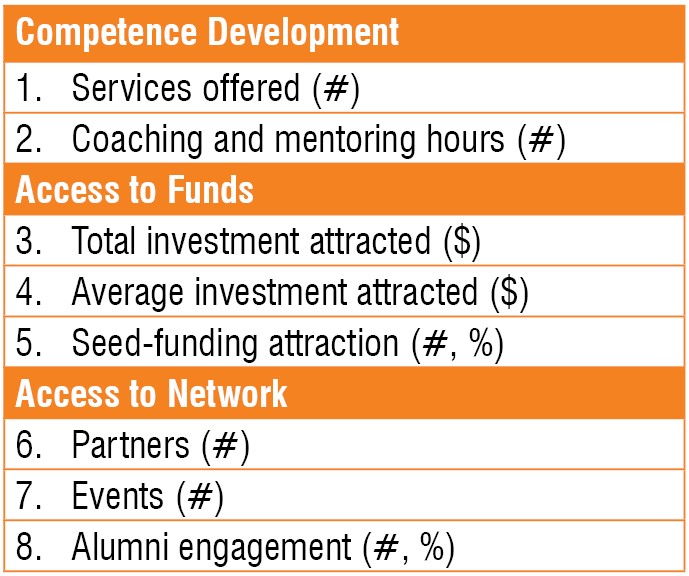

The Value for Client Start-ups category assesses the number and efficiency of services provided by the programs. Numerous studies have shown that the quantity and quality of services provided is a crucial indicator of long-term start-up success. Of equal importance for individual start-ups – as well as for the ecosystem in general – is the program’s function as a facilitator of community- and network-building. The subcategories Competence Development, Access to Funds, and Access to Network encompass a total of eight KPIs.

Competence Development

The Value for Program category assesses program success in attracting deal flow and third-party support as well as the capacity to create viable companies. The subcategories Program Attractiveness and Post-Graduation Performance encompass a total of seven KPIs.

Program Attractiveness

In order for an incubator to evaluate itself using these KPIs, it is important to understand the different weights used for each criterion, which is explained in the table below.*

The study and the UBI KPIs can help the incubators to better design and enhance their current and future programs. For example, incubators can develop their strategies based on specific success criteria. These can address the employment of youth, revenues generated by the start-up, or the networking and number of clients reached.

The mentioned KPIs can also help the administration level to track specific information for their reporting, which leads to a better evaluation of the programs and enables them to be more successful.

Incubators in the Gaza Strip should work with a shared vision and strategy, and there should be a higher level of synergy among the various projects and initiatives related to the entrepreneurship sector in the Strip. The KPIs mentioned by UBI can be selected and adopted to improve the current performance of the Gaza incubators, but priority should be given to specific KPIs, based on the three levels: the administrative level, the incubation level, and networking.

Furthermore, incubators should design their programs based on their strategies and adapt to donor requirements based on the common ground they share. The current situation is proving that most incubators are donor-driven with no clear strategy for their future programs.

In addition, more work should be done to integrate research, academia, the private sector, and other components of the entrepreneurship ecosystem into the incubators’ programs.

The criteria for the selection of start-ups should be more flexible and must allow innovative ideas to be selected. Thus, alternative methods of selection must be created that also shorten the currently very long selection process.

Ideally, mentors in the incubators would receive international training, enabling them to gain a greater understanding of the mentoring and coaching processes and to acquire more experience regarding international best practices and standards.

Finally, Gaza’s incubators should collaborate, streamlining their efforts through creating a unified database of beneficiaries to organize the selection process of start-ups; coordinating the networking efforts to have better future opportunities for outreach to external markets; and planning regular meetings to collaborate and organize the scheduled events throughout the year.

*Source: The UBI Global world ranking of business incubators and accelerators report – 2019

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, including UNDP and other UN agencies.