We believe in that which hath been revealed unto us and revealed unto you; our Allah and your Allah is One, and unto Him we surrender. Al-Qur’an29/46

We believe in Allah, and the revelation given to us, and to Abraham, Isma’il, Isaac, Jacob, and the Tribes, and that given to Moses and Jesus, and that given to (all) prophets from their Lord: We make no difference between one and another of them: And we bow to Allah (in Islam). Al-Qur’an 136/2

God Speaks Aramaic!” insisted Gilda.

“God Speaks Arabic,” my sister countered.

Gaby and I silently followed the morning chatter between his sister Gilda and my sister Suhad as we whiled away the time waiting for the school bus. I was barely seven years old.

“The Lord spoke our language, and we shall be the first to gain admittance to heaven,” Gilda persisted.

“No, Allah speaks Arabic,” my sister Suhad would contend. “The Qur’an is in Arabic, and it is the language of God in heaven.”

“We will be the first ushered into heaven, for Arabic is the spoken language in paradise!”

The girls’ prattle would end when the voice of Diana, Gilda’s older sister, broke into loud sobs, marking the end of her daily morning row with her father. Every morning Diana, 12 years old, mounted the same scene. She wanted a horse.

“Dad refuses to buy her a horse,” Gilda sadly explained. “Where would we put it?”

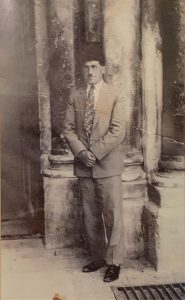

For the past century, Jerusalem has stood apart from the rest of Palestine with its distinctive cosmopolitan character. From all over Palestine, parents would send off their children to Jerusalem’s boarding schools. For the girls, there were many options: Schmidt School, the Sisters of Zion, the Rosary Sisters, the Jerusalem Girls’ College, etc. The boys would invariably be sent to the Frères School, Terra Santa, or St. George. Ours was not the first Muslim generation in missionary schools. In fact, I was registered there by my grandfather, Jacob Nusseibeh, himself a graduate of the Frères high school, a student of the famous biblical archaeologist William Foxwell Albright. In fact, he is one of the Muslim custodians of the key to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, an honor that the family have passed on from father to son as the first noble patrician Arab family from Medina to settle in Jerusalem in the seventh century, and the offspring of the first Muslim governor of Jerusalem.

I still remember the sunny morning fifty years ago when my grandfather and father took me by the hand up the stairs that led from the Church of the Holy Sepulcher towards Casa Nova Hotel, past St. Demetrius Monastery, a curving lane, then more steps and past the Pontifical Mission Library to register me at the Frères’ school at New Gate. By the turn of the twentieth century, Christian missions in Jerusalem had already succeeded in providing a safe locus whereby the local Arab population could profit from full exposure to Western civilization. Within the context of the Christian missions, the privileged Jerusalemite had the better of the two worlds. One slept in the shadow of the Dome of the Rock in the Muslim Quarter but spent the school day in the Christian Quarter studying under the tutelage of French, Italian, Spanish, Maltese, Irish, and German friars.

Baudelaire, Keats, and Wordsworth; Moliere, Racine, and Shakespeare; Charles Dickens, the Brontës, and D.H. Lawrence infused our lives with compassion and the lust for life and meaning.

The overall education, occupational pursuits, economic conditions, and way of life of the Jerusalemites encapsulate the profile of the Palestinian-Arab middle class: bourgeois, generally well-educated, with an occupational structure similar to that of the new classes that began to emerge in the West starting in the late-eighteenth century. Cultured, professional, relatively well-off individuals lived communally. They tended to share common interests, often having common values and beliefs, as well as shared property, possessions, resources, and, in some cases, work, income, or assets.

“My mother, God bless her soul, never stopped talking of Hussein Qleibo,”my friend Nora Qort reminisced nostalgically. “He was the best friend of my uncle Habib. They bought the same pinned-collar-style shirts together, the same cufflinks, and even the same house crockery on which they put the family initials.” Nora continued, “All is preserved in the museum Wujud.”

Throughout my life, my father talked fondly of his good friend Habib Qort. They spent all their time together and shared their love of music. Dad played the piano and had a good voice, and Zahieh, Nora’s mother, was a proficient pianist endowed with a good voice. Love of music is binding, and the friendship deepened with time. Home visits were joyful moments of piano and songs. Communal Christian-Muslim social life before the loss of Palestine, prior to Al-Nakba, had a different timbre. People had more leisurely time, and human relations were highly valued and cherished. When Habib died prematurely, my father, as was customary, assumed a protective role towards Zahieh. He matched his friend Samaan Qort, who was the director of the modern printing press in Dar al-Aytam (the Muslim orphanage) with Nora’s mother.

“My father, Samaan Qort, though from the same family, was a distant relative and a close friend of your father… it was a perfect match!”

Nijmeh Kharoufeh was another close friend of my father. A major enterpriser during the British Mandate, she was the first to market Palestinian embroidery as folk art for tourists to buy. Her shop on Sweqet Allun (David Street), still run by her nephews, was across from my father’s shop where he traded wholesale with flour, rice, and sugar.

Next to Nijmeh Kharoufeh was the famous shop of Havelio, celebrated for its halawa and luqom (Turkish delights). Mr. Havelio, an observant Palestinian Jew, used to buy his sugar from my father. His son Abraham, who passed away in his late nineties a few years ago, adopted us as family friends after Al-Naksa. He once showed me the receipts for the transactions of sugar purchases, filled out and signed by my cousin Aref Qleibo who did the family accounting.

“Muslims and Greek Orthodox Christians (al-Rum) were close to each other because both were Oriental,” Nora explained. As I listened to her, I remembered the words of Mr. Havelio. He had said that it was easier for the Jews to become friends with Muslims and visit them at home since Muslims do not have crosses on the wall… and because of the shared concept of halal and kosher food.

“Should we have to walk to the Christian Quarter from Suq Khan al-Zeit, we would avoid passing the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, though it is a shortcut, and would go around the long way from Al-Dabbagha.” Havelio’s words echoed as I listened to Nora.

Muslims, on the other hand, felt at ease with the cross and the church. Jesus, after all, is a recognized and deferred-to prophet – a precursor of Mohammad – and the Virgin is hallowed and selected above all women in the Qur’an.

The villa in which lived Nijmeh and her sister, a famous couturier of the period, stands in testimony to their great affluence. Though they hail from Beit Jala, the two independent ladies amassed great wealth and built a villa of palatial dimensions in Qatamon. Religious affiliation was not an issue that my father spoke of. I did not know Nijmeh was Christian until years later when Abraham Havelio told me.

“People become friends because they have common interests, shared values, and similar lifestyles,” my dear friend Monica Awad pointed out. The fact that one goes to a church or to a mosque is a minor detail. “Communal Christian-Muslim life was based on a common life, with common objectives and common interests in a small homogenous society.” She concluded, “You are not my friend because you are Muslim, you are my friend because of all the details we have in common!”

Under Israeli military occupation, Jerusalem has undergone a radical demographic transformation that parallels both the expansion of the municipal boundaries of East Jerusalem, an unprecedented rise in the economic standard of living of its Palestinian residents, and the corresponding deployment of heterogeneous ethnic lifestyles.

After the Six-Day War, the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem expanded southward and northward. Greater Jerusalem has been extended to include 28 villages, from Isawiyeh in the north to the villages of Silwan, Abu Tor, Jabal al-Mukaber, and Sur Baher in the south, to name a few. Correspondingly, the demography of Jerusalem changed drastically. In the Israeli economic context, extensive employment opportunities have leveled the socioeconomic and cultural barriers between the traditional Palestinian aristocracy and, some say, haughty bourgeois population on the one hand, and the impoverished Arab peasants and Bedouins in the adjacent villages, on the other.

The combination of a heterogeneous, multicultural ethnic identity, a socioeconomically mobile middle class composed of migrants from Mount Hebron, and the Bedouin and peasant communities from the 23 Palestinian villages that comprise greater Jerusalem, has emerged and dissolved the once closed, homogeneous Jerusalem Arab bourgeois society to become a modern ethnically heterogeneous city.

Fifty years after al-Nakseh, or the 1967 Six-Day War, greater East Jerusalem has become a multicultural city. The indigenous educated professional and Western-oriented middle class sustained the greatest blow. “The brain drain” and the massive middle-class urban emigration consequent to the fall of West Jerusalem in 1948 is one of the main causes underlying the drastic transformation of the elite and bourgeois character of Jerusalem. In the nationalist opposition to the Israeli occupation, both religions have been politically instrumentalized to the extent that the Christian community and the Muslim community have developed distinct resistance discourses. Mediocre academicians and theologians found fertile ground in advancing the malaise of their respective ethnic religious by highlighting their own grievances under occupation thereby inadvertently fostering the rift between the Christian and Muslim, presenting each group as having its own separate threats!

Throughout history, religion among Palestinians was merely an element of individual identity but never a defining element. Before the Nakba, Jerusalem was a small city composed of a relatively homogeneous closely knit Christian-Muslim community. Since Jerusalem was economically prosperous, the Arab population lived in general conviviality. Christians and Muslims worked together, held common interests and common values, and lived together. Few cosmopolitan bourgeois Jerusalemites stayed steadfast in their hometown. Estranged, the few that have remained are dinosaurs, an endangered species. We have become a minority in our hometown.

“Al dam bihin” (الدم بحن). My late friend Yasmine Zahran used the Arabic idiom “blood bonds” to explain the attraction and many marriages of Jerusalem Muslim males from patrician families to the Assyrian females well into the 1960s. “The Assyrians are of the same cultural genetic pool. In fact, Aramaic girls, al-Syrianiyat, were known for their beauty, and in my childhood, it was a big community. There was a massive migration to Jerusalem and Bethlehem, notably from northern Syria and southern Turkey in the late-Ottoman period. Al-Syrianiyat from Mardin were the great beauties. Dr. Zahran, a specialist in the Chaldean religion, held the common belief that al-Syriyan (the Assyrians) were the original Jerusalemites before the church moved to Antioch in the early days of Christianity.

“Our piano was kept in our family church.” Nora’s Greek Orthodox family had their own family church on the hilltop of Montefiore near the Windmill. “Our olive groves stood there. My grandfather had several visions of Saint George, al-Khader, who enjoined him to build the church on the land.”

“All is lost. Palestine is lost,” Nora lamented.

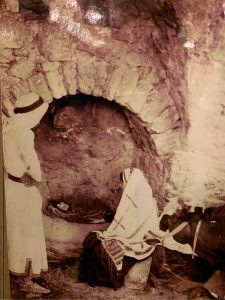

Saint George/al-Khader strikes deep roots in the Palestinian psyche, testifying to our common primordial Canaanite roots. The churches in the town of Al-Khader, south of Bethlehem where St. George lived, and in Lydda, where he was born, attract Muslim and Christian supplicants alike. In a country where often the sacred spaces belong to one religious community to the exclusion of the other, the Saint George churches remain an exception because of his exalted position to both groups. Neither the Christian nor the Muslim narratives succeeded in eradicating the native Palestinian psycho-religious attachment to and devotional rituals surrounding the Canaanite rider of the clouds, the god of thunder, rain, and fertility. The different forms of ancient Semitic blood sacrifices survived until modernity as acts of devotion to al-Khader/Saint George. Ironically, while al-Khader is revered by Muslims as a holy man (ولي), the Christians see him as a saint. Whereas, in the Ottoman period, a separate mosque was annexed to his tomb in Lod, Muslim supplicants perceive the Greek Church in the town of Al-Khader as a maqam, a Muslim sanctuary.

This same church in Al-Khader, southwest of Bethlehem, was the favored site for baptisms and circumcisions by Christians and Muslims alike. In 1848, following the restoration of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, a priest wrote about his concern that Palestinian Christians could not be distinguished from Muslims. A Christian was distinguished only by the fact that he or she belonged to a particular clan, he noted. If a certain tribe was Christian, then individuals belonging to that tribe would be Christian, but without knowing what distinguished their faith from that of Muslims. Indeed, the situation was confusing: Many Muslims even had their children baptized at Al-Khader because tradition maintained that a child baptized there would be strong.

Unfortunately, anthropologists often arrive too late to the scene. The priest’s main concern, namely, to save souls, precluded ethnographic research. Who, how, and with which words did Muslims baptize and Christians circumcise at Al-Khader are questions that remain veiled in mystery. The thick description of their worldview did not interest the priest but was viewed with a sense of alarm. A century and a half later, the information can be partially recovered through the recollections of the grandchildren through individually conducted interviews. Since then, both the church and Muslim orthodoxy have penetrated the countryside. Nowadays a Muslim sacrifice to Saint George is considered shirk (شرك), a form of idolatry. The various forms of pagan rituals of blood sacrifice, such as burning the blood sacrifice, are now abandoned. Only one kind of Christian thabihah has survived wherein the entire sacrificial lamb is donated to an orphanage or a home for the aged. The blood of the sacrifice is considered blessed, and both Christians and Muslims dab their palms in the blood to bless the entrance of a house with their handprint, using the talismanic number five to ward off evil.

On the way to Dura, I dropped by to see my old friend, Um Nassar, in Beit Ummar. Though already April, it was cold, and despite my numerous winter visits, I was led for the first time into the living room. On the wall there was a picture of the Virgin carrying baby Jesus!

“I thought you were Muslim!” Anthropologists can’t be shy.

The 86-year-old lady smiled timidly.

“We used to be Christian … and it feels good to have the Virgin Mary,” her daughter said matter-of-factly.

“Our ancestors on mother’s side came with the Second Crusade in the twelfth century. They were two brothers. One stayed in Nablus and remained Christian. His brother, our grandfather, came south and became Muslim,” her nephew Walid explained.

“It has been a long time. I was getting worried.” Um Nassar was happy to see me. “My son wants you to visit him in his house. Let’s have our coffee there.”

We drove through the back streets of the village. I saw a sanctuary…

“It is Matta (Arabic for Matthew).” Um Nassar recited the Fatiha, a verse from the Quran, as we passed.