Nineteenth-century travelers – be they pious pilgrims or visionary poets, righteous missionaries or libertine dilettantes, Muslim, Christian, or Jew – had already experienced Jerusalem through sacred scripture, traditional religious narratives, and travelogues prior to their arrival in Palestine. Muslim literature has throughout the centuries deployed a special literary discourse extolling the virtues of Jerusalem and laying out the itinerary for Muslim pilgrims, outlining places of significance associated with Prophet Mohammad and Abraham. Christian and Jewish pilgrims were attracted by Biblical stories and by the scenes of the last days of Jesus in Jerusalem as described in the New and Old testaments. The firsthand narratives of the Holy Land and the Near East by nineteenth-century authors, such as Herman Melville, Mark Twain, François-René de Chateaubriand, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Gustave Flaubert, further inflamed the European imagination about the Orient.

The story of the rediscovery and Western exploration of the Holy Land in the nineteenth century is a fascinating chapter in the long history of religious and secular tourism in Palestine. Napoleon may not have visited Jerusalem during his occupation of Palestine, but in his expedition a slew of scientists came along. Their documentation of Egypt and Palestine sparked Western imagination and initiated great interest in the Ancient Near East and the Land of the Bible. Palestine had been terra incognita from a scientific point of view, but by the end of the century, the foundations for the scientific study of the country were firmly laid down. Surveys, maps, traveler’s sketches, guidebooks, and artists’ paintings and engravings brought the people and scenery of the land to the attention of the Western public.

Once steamships replaced the old sailboats, travel time across the Mediterranean was dramatically reduced and made easier. The three-week lengthy distance from London to Istanbul took less than a hundred hours. Various travel itineraries were developed by the 1830s. The steamboat stops in Napoli, Malta, Alexandria, Izmir, Salonika, Athens, Venice, Constantinople, and Jaffa transformed the Mediterranean into an easily traversable lake. It is in one of these early steamships that the famous obelisk was transported from Luxor to its current position in Place de la Concorde in Paris! With the newly forged alliances with Turkey, the Mediterranean enjoyed an unprecedented state of safety. Shortly after the Egyptian campaign in Palestine and the Crimean War, the newly wedged alliances, and the corollary Ottoman concessions, the Near East became part of the classical European tour. By 1870, Egypt had become top choice as a winter-season resort, and Palestine had its share of enthusiastic visitors.

The publicity of various navigation companies to promote the new mode of travel included inviting great authors free of charge provided they would write of the comfort of steamboat travel. The list of these illustrious guests – novelists, poets, travel writers, scholars, and journalists – is extensive and includes Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Chateaubriand, Flaubert, and Lamartine. Travelers increased; the faithful and the nonconformist, the dilettante and the biblical scholar, the missionary and the debauched; all flocked from all the corners of the earth to Jerusalem. As early as 1869, the carriage road from Jaffa to Jerusalem was paved to accommodate royalty for a side trip to the Holy City after attending the opening of the Suez Canal and the grandiose opera house in Cairo.

Political and economic developments, improved standards of living, scientific discoveries, and massive literary output allowed for the tourist industry to thrive. By the early 1840s, foreign missions were established. The first, in 1839, was the British Consulate on Melawiyah Road. Germany came next in 1842, and soon after, France, Italy, Austria, and Russia followed suit.

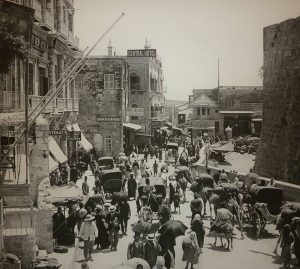

The Mediterranean Hotel

Formerly the residence of the English bishop, the Mediterranean Hotel was the first luxury hotel in Jerusalem. Before 1850, any traveler would have to put up at one of the convents, his servant providing his meals, or take lodging in some private house. By 1853, two inns, the “Mediterranean” and the “Maltese,” were established. The Mediterranean occupied two different locations prior to its permanent home inside Jaffa Gate. According to Cook’s Tourist’s Handbook in 1876, the Mediterranean Hotel was regarded as the “best in Jerusalem.”

As it changed owners, the name changed: Hotel de l’Europe, Grand Hotel, Dordenells, Central Hotel, and Hotel Continental. Now it is known as the Petra Hotel. The establishment is of particular importance in the social history of Jerusalem. Several of the Palestine Exploration Fund explorers lodged there, including Charles Warren, R. W. Stewart, and Claude R. Conder. Its relationship to the millennialists is reflected in its common name, The Hauser Hotel, after Christian Hauser and his wife who ran the hotel. They were succeeded by Moses Hornstein, a converted Jew whose son, C. A. Hornstein, was the principal of the London Jewish Society/Bishop Gobat Boys’ School. Significantly, Christ Church, across the street, was the first Protestant church in the Middle East. The church was built between 1842 and 1849 by the London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews for the specific purpose of converting Jews.

The hotel occupied the two upper floors of the building as well as some of the storerooms on the ground floor, but the shop in front was rented out separately by the Amzalak family. In 1870, the shop was rented to Max Ungar, a German tailor, and then to Joseph Hayat next to the Meo family souvenir store.

Numerous incipient discourses were forming along Orientalist colonialist lines (the analysis of which is beyond the scope of this article). The Ottomans astutely protected their hegemony over the many ethnic groups and maintained their Western alliances through the deployment of major series of reformations initiated after the Crimean War and known as the Tanzimat, constitutional reforms. In 1872, Sultan Abdulaziz was deposed by his ministers, killed, and replaced by Sultan Abdel Hamid II. Soon after, the second Tanzimat were issued whereby foreigners were given rights to purchase land in Palestine. The millet system granted the various ethnic groups in Jerusalem, and the empire at large, legal rights and protection by the law, including the right to purchase property. The first local newspaper, Filistin, in Turkish, was launched that year. Jerusalem was declared an independent mutasarrifieh and encompassed all the provinces that constitute present-day Palestine. According to Baedeker, the total population was 24,000, of which 13,000 were Muslim, 7,000 Christian, and 4,000 Jewish. It was a period of prosperity, stability, and relative peace; elements that were propitious for the religious and secular tourism industry, a period in which the foreigners often outnumbered the local population.

Nineteenth-century travelers included writers, poets, and painters who toured with their Bibles in their hands to “read” the landscape and the realities of the Holy Land against a sacred text. Though the majority of voyagers were religious pilgrims inspired by the Holy Scripture, a substantial number of tourists, the secular literati, travelled to Jerusalem to identify with the universe through expatriation. They were not typical travelers. Rather literary tourists, they were seekers of textual evidences as they quested for meaning and identity, in search of a meaningful personal encounter with the Holy Land. It is one of the characteristics of Palestine that so many travelers “see” the place through the distorting lenses of their sacred texts, cultural myths, and national narratives.

Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf and her lover, the writer Sophie Elkan, set off for Jerusalem. Like other tourists, travelers, and pioneers, Selma had to deal with the giant gap between the dream and the reality, between the sublime Jerusalem of gold and light and the real Jerusalem of grey, mildewed stone houses. Her account of her experiences would be the basis of her book that eventually led to her being awarded the 1909 Nobel Prize for Literature.

She connected with the other Swedish pioneers who had already set up a colony (which through marriage developed in later years into the American Colony). As farmers, they contributed to the development of the local agriculture, sowed wheat fields near the colony, and grew potatoes, grapes, and olives. They built chicken coops and a dairy barn and started a dairy industry. They established a weaving and embroidery factory and a bakery. They were also pioneers in the field of photography in the country, with a photo shop selling their postcards inside Jaffa Gate. Their lodging facilities, restaurant, and extensive connections among the Palestinians and foreign expatriates made the colony a nodal point of social network.

The Mutasarrifiat of Jerusalem (متصرفية القدس الشريف), established in 1872, was an Ottoman sanjak (province) with special administrative status. The Jerusalem sanjak, which was referred to as Mutasarrifiat al-Quds ash-Sharif, encompassed Bethlehem, Hebron, Jaffa, Gaza, and Beersheba. Initially, the district was separated from Damascus and placed directly under the Ottoman central government in Constantinople in 1841, and was formally created as an independent province in 1872. Together with the sanjak of Nablus and the sanjak of Akka (Acre), it formed the region that was commonly referred to as “Palestine.” It was the seventh most heavily populated region of the Ottoman Empire’s 36 provinces.

Mark Twain, who visited Jerusalem in 1867, noted that all peoples, races, religions, and languages were there. In his book, Innocents Abroad, an edited compilation of his published newspaper articles and journal describing his travels to Palestine, he wrote:

“It seems to me that all races and colors and tongues of the earth must be represented among the fourteen thousand souls that dwell in Jerusalem.”

The number of publications on the Holy Land by nineteenth-century Western writers is astounding. Handbooks for travelers, the precursor of modern guidebooks, provided extensive itineraries for travelers. The first English-language guidebook was published in 1858 by John Murray, Handbook for Travelers in Syria and Palestine. A few years later, it was followed by Karl Baedeker’s Palestine and Syria, Handbook for Travelers. The guidebook first appeared in German in 1875 and in English in 1876.

The flood of travelers and itinerant tourists increased the demand for Murray’s guidebook that had many reprints. The publisher Josiah Leslie Porter, who described in the foreword the various motives underlying the rage to travel, wrote: “One is in pursuit of health, another of pleasure, another of fame, another of knowledge; another of adventure; while not a few travel for the mere sake of travel – to satisfy a restless and ‘truant’ disposition.”

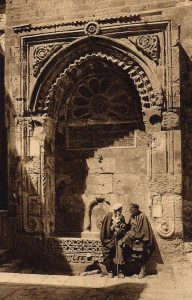

Travelers arriving in Jerusalem in 1876 beheld an urban landscape distinctly different from the city we have come to know. Imagine Jerusalem without the belfries of the Lutheran Church or of the Franciscan tower! Imagine the city without Notre Dame, the Dominican convent, Augusta Victoria, or Dormition Abbey… Apart from the Russian compound –which hosted Russian pilgrims – and a few scattered Palestinian family castles belonging to Jerusalem’s patrician families, namely Al-Ansari, Al-Khateeb, Al-Muwaqet, Al-Hidmi, Nusseibeh, and that of my family, Jerusalem was entirely confined within the Old City walls! Travelers inured to the hardships of travel, exposure to sun and heat, were overwhelmed by Jerusalem’s magical allure. Recounting his visit to the Mount of Olives, traveler Edward D. Clarke described the spectacular vista: “We had not been prepared for the grandeur of the spectacle which the city alone exhibited. Instead of a wretched and ruined town, by some described as the desolate remnant of Jerusalem, we beheld a magnificent assemblage of domes, towers, palaces, churches, and monasteries, all of which, glittering in the sun’s rays, shone with inconceivable splendor.”

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Jerusalem lived its golden age. Missionaries – Protestant, Catholic, and Greek Orthodox – flocked to the city: Germans, Swedes, Finns, and Swiss Lutherans found an embodiment of their faith. The Millennialists had started their mission in anticipation of the second coming of Jesus; they flocked to Jerusalem to convert the Jews to be ready for the Day of Judgment. Various missionary schools, clinics, and hotels were being built – the Zion Boys School headed by Bishop Gobat, the Schneller Vocational Training School, German Colony. The De La Salle Brothers had settled in Jerusalem and were to begin to build the Collège des Frères, the best school in Palestine. Augusta Victoria, the Dominican convent, and Dormition Abbey were in the making. This was an exciting moment.

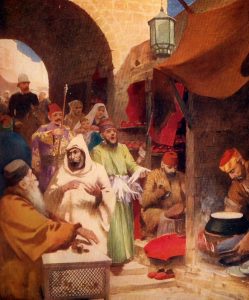

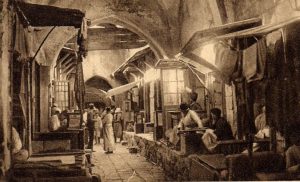

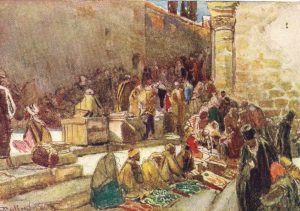

In the travel books, Jerusalem was promoted as a marvelous city where peoples and cultures coexisted; a cosmopolitan city. Citadel Square within Jaffa Gate (Omar Ibn al-Khattab Square) was lined with Thomas Cook’s Travel Bureau, the American Colony Photography Shop, the Meo family souvenir shop, and the grandiose Mediterranean Hotel (now Petra Hotel) on the northern side counterpoised by the American Consulate and the post office on the eastern side. William Hepworth Dixon, in his travel book The Holy Land (1863), describes the spectacular comingling of whirling Sufi dervishes and Armenian monks with pointed hoods, the naked Nubian slave on sale, and the kavas (the ceremonial consular guards with their crimson jackets laced with golden thread and loose-fitting pantaloons), the colorful Moroccan mystics, Bedouin sheikhs clad in white, and Indian and Afghani Muslim pilgrims next to the German, Swiss, and American missionaries dressed in their national ethnic costumes… He writes of the magic of Jerusalem:

“All centuries, all nations, seem to hustle each other in this open court under David’s tower. In pushing through the crowd of men, you may chance to run against a turbaned Turk. A gaudi cavas, a naked Nubian, a shaven Carmelite, a bearded papa, a robed Armenian, an English sailor, a Circassian chief, a basha and a converted Jew. In crossing from the gateway to the convent you may stumble on a dancing dervish: you may catch the glance of a veiled beauty; you may break a procession of Arab schoolgirls headed by a British headmistress.”

Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick, described his experience in Jerusalem in the longest epic poem in Western history, Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land. The oeuvre is longer than Homer’s Iliad and Milton’s Paradise Lost, and in conjunction with the journal he had kept on his voyage, he proffers Jerusalem as a marvelous and mystical city. Melville’s descriptions and reflections, his spiritual longing and ultimate disenchantment punctuate the development of another remarkable narrative – that between the traveler and the Holy Land: namely the quest for identity through immersion in experiencing otherness.

In his journal we glimpse a Jerusalem that is dynamic, vital, and energetic with things budding everywhere. It is the period when the city was teeming with all kinds of people, and dreams were in the making. Melville’s narrative underscores the global and plural character of Palestine, presenting it as a polyglot world where culture and peoples circulate and interact and where creeds dovetail into each other….

Ottoman Jerusalem is a microcosm, a context representative of the diversity of humanity and human visions of the world. Jerusalem and Palestine are the global contexts where multiple cultures come together in what constitutes a representative sample of humanity. Americans, Europeans, Asians, Africans; Muslims, Jews, Christians; Roman Catholics, Greek Orthodox, Calvinists, Anglicans, Dominicans, Franciscans, atheists, devout believers, hedonists, and lunatics encounter one another in the emblematic city of Jerusalem which in the twentieth century was to become the core of tragic human collisions.