“So they wouldn’t send him to die like cannon fodder.” This is the first reason that José Elías Aboid lists to explain why his grandfather left his native Palestine to travel to Chile, the farthest corner of the world.

“The situation of the Christians in the Ottoman Turkish Empire was not easy, not only because of the overcharging of taxes imposed on them but also because they were forced to enlist in wars that they had nothing to do with. They were recruited to fight on the front lines and were sent to die,” explains José, sitting in the middle of the living room of his apartment.

José is 81 years old. He covers his two-meter-high body with a dark-blue robe. His soft and scratchy voice contrasts with his size but combines with his wisdom of stone, matured and macerated after decades of study.

Drinking a cup of tea mixed with three tablespoons of sugar, he travels to the past, what he remembers of it, to talk about his grandfather Juan Elías Zaied, the first man in his paternal family to step onto Chilean territory.

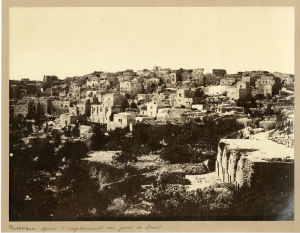

Juan Elías Zaied lived until the end of the nineteenth century in what was then known as Palestine. At that time all that territory, including Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, was part of the Ottoman Turkish Empire. He resided with his clan in Beit Jala, which, according to José, in those days would not have had more than 8,000 inhabitants. They dedicated themselves to tilling the land, bartering, and working in construction.

Juan was the eldest of five brothers. When his father, Elías Zaied, died after a fulminating stomach illness, he was forced to assume all responsibility and take care of the whole family. He was barely twenty years old.

Driven by the imminent danger of being recruited by the Turkish army, added to the very poor economic situation, Juan Elías decided to leave his land and set forth to Latin America. For some years now, letters had been arriving from the first Palestinian people who ventured to the other side of the world. They talked about the good weather and, above all, the possibility of a better life in Chile.

In the early 1900s, Juan Elías, a brother-in-law of his, Nicolás Majluf, and a maternal uncle, Jorge Eluti, took a steamboat on the coast of what is now Syria to Genoa (Italy). It was a long-term bet full of risks, which is why only men left. Women and children were left behind.

From Genoa they boarded another ship heading to Buenos Aires, Argentina. The most complex part was crossing the Andes Mountains from Argentina to Chile. In the three weeks that the trip lasted, a guide accompanied them, but the road was narrow and dangerous in many parts. In total it was an exhausting journey of three and a half months.

“In Chile, Palestinian names were often cut short or modified by the registration authorities. When Juan arrived with his Turkish passport, his official identity was Juan Elías Zaied, but Zaied was eliminated. This is the reason that my family’s last name is now Juan’s father’s name: Elías,” explains José.

The letters not only spoke of Chilean perks, they also warned of a discriminatory treatment towards Arabs, what became known as “Turkishing.” They also said that, in the capital, Santiago, the reception was even worse, so the three men decided to settle in southern Chile, in the city of Victoria.

“Their priority was to get settled and raise money to bring the rest of the family over. They started as street vendors. They brought religious articles from the Holy Land because they were told that in Chile these products were highly valued,” recalls José.

Nicolás Majluf Sapag is the grandson of Nicolás Majluf, who crossed the Andes Mountains together with Juan Elías. “I was born six months after my grandfather died. My name was also a comfort to my grandmother who would say: Nicolás died, but Nicolás was born,” he explains.

“Our grandparents were illiterate, poor farmers. When they arrived in Chile, they had to apply all their efforts and wit to enable these numerous families to rise above the difficult conditions surrounding them. Their stories speak of people motivated by hard work. In time, they managed to improve their economic condition, and we as a third generation could already go to study at universities,” says Nicolás Majluf.

Two years after the arrival of the men, the women undertook their trip to Latin America. Each family started its own business, and at the beginning they specialized in the sale of household items.

“Women worked side by side with men. They saved a lot of money, which meant that they had to lead austere lifestyles. Sometimes they gave themselves the luxury of buying lamb to prepare Arabic food. It wasn’t that expensive, but for them it was still a lot of money,” explains José Elías.

Juan Elías was married to Farja Param. In Chile they had five children: Osvaldo (father of José Elías), Maruka, Emilio, Elías, and Lidia. They moved to Santiago in 1936 and settled in the Buenos Aires street of the Patronato neighborhood, known as “little Palestine,” because of the many Palestinians who lived there.

“There was a tremendous sense of community until about the sixties. We all lived close together and helped each other. We went on vacation all together: the Majlufs, the Elutis, the Eliases, and we practically rented the entire hotel. I remember that José Elías was a very elegant young man who hated getting his feet wet in the sea,” says Nicolás Majluf, laughing at the memory.

A year after his arrival in the capital, the Elías family opened the Brooklyn Socks Company. Furthermore, they later specialized in other textiles and opened factories in the El Salto sector. The street where they settled was baptized with the name of its creator: Juan Elías.

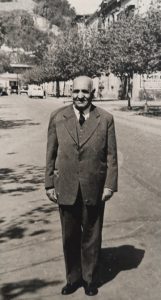

His granddaughter Sara Elías remembers him while she looks at some old black and white photos that she delicately takes out of a leather case. “My grandfather was an elegant man, and he liked that we always looked well presented. Sometimes he gave me money and asked: “Did you go to the hairdresser?” And I would answer “yes grandpa.” “Show me your hands,” he would reply, and I would stretch them out so that he could study them. “I don’t like them that way,” he would reply sometimes,” Sara laughingly remembers.

“He was a cool man, my grandfather,” says Juan Elías, another of his grandchildren. “For Saint Juan Day there were tremendous parties at his house, which was always full of people. He was a very sociable person, and everybody respected him because he was among the first to come to Chile.

José Elías and I were his favorite grandchildren. My grandfather took me for road trips to El Arrayan. Sometimes when he told me to go with him, I replied, “But grandpa, I have to go to school,” and he shouted back: “F*** school!” And that was it. Nothing else mattered. We got in the car and took off, singing songs in Arabic”, says Juan.

Juan Elías Zaied died in 1967 in Santiago, Chile surrounded by his beloved family.

“It is important to highlight the contributions that the Palestinians brought to Chile. The culture and the food are important, yes, but the really beautiful thing that our grandparents brought to Chile was a new way of living with each other, a warm and affectionate way to treat one another,” concludes Nicolás Majluf.