Of all the travelers passing through the Dabdoub house, the one who most captured Jubrail’s childhood imagination was Ammo Hanna. At that time, the Dabdoub house, known to all as Hosh Dabdoub, was like a travelers’ way station. Perched on the edge of the steep northern slopes of Ras Ifteis, it was the first house that travelers came across on the approach road into Bethlehem. All manner of visitors would call by to purchase souvenirs or discuss politics and local gossip, which in those days were one and the same. But Ammo Hanna held a special fascination for Jubrail.

His real name was Hanna Khalil Ibrahim Morcos, but Jubrail called him ammo as a term of affection.*1 Ammo Hanna had travelled to the farthest reaches of the known world and was a walking repository of fantastical stories. He would turn up at the hosh unannounced and sit with Jubrail’s father and elder brothers under the arches of the house’s riwaq arcade that looked out over the terraced valleys below. Leaning back against the mattresses and cushions of the diwan, they would sip coffee and puff on argileh pipes as they took in the sea of olive groves that stretched to the east and then gave way to the more barren hills of the Wilderness. Jubrail would wait patiently while the men discussed new clients in Jerusalem, exchange rates between strange-sounding foreign currencies, and how they might profit from the upsurge in Russian pilgrims. When the conversation died down and Jubrail’s father began to doze in the afternoon sun, the young boy would tug on Ammo Hanna’s abayeh, begging him to tell him stories of the mysterious land he called Amerka.

Ammo Hanna was not the only person in Bethlehem who had travelled abroad in those days. Alongside the pilgrims, friars, mystics, and dignitaries who regularly passed through town, a handful of local merchants had ventured across the Mediterranean to the western-most reaches of Europe. The people there were known as afaranja, or franji in the singular: a strange breed of person that could be regularly sighted in Bethlehem. For some unknown reason, the afaranja felt the need to meddle constantly in the affairs of others, even when circumstance seemed to demand a humbler approach.

Over many centuries of interaction, the Bethlehemites had learned how to turn the arrogance of the afaranja to their advantage, even if it sometimes put them at odds with the rest of the local population. People still remembered a man named Abdallah Hazboun who had decided to join the army of a particularly haughty franji general named Napoleon, to work for him as an interpreter. The army of this general had swept across Egypt and Palestine at the turn of the century, attracting a few ambitious locals along the way. When the army was defeated at Acre, the new recruits found themselves in a delicate position. Facing a choice between the vengeance of the local population or retreat with the franji armies, Abdallah had wisely chosen the latter, travelling with Napoleon all the way back to France. It was said that he had met with great success there, living in Paris with a franji wife and embarking on further military expeditions abroad, where he continued to help the French armies meddle in the affairs of others.*2

Jubrail was familiar with these characters who had entered Bethlehem legend as the first to travel to the lands of the afaranja. But it was Ammo Hanna and his tales of Amerka that truly captivated him. A-M-E-R-K-A. Even the word itself sounded exotic and exciting. The generation of Jubrail’s father still spoke about a man named Andrea Dawid who had set out for Amerka a hundred years ago but never came back. Word had reached Bethlehem of his death in 1796, but the event remained shrouded in mystery.*3 The Dawid family lived across the road from Hosh Dabdoub, and they frequently discussed the fate of Andrea without ever reaching a consensus. Some said he had been consumed by fearsome jinn dwelling in the mountain caves of Amerka, while others claimed he had been devoured by sea monsters during the return voyage.

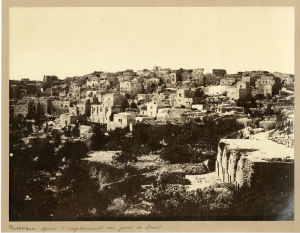

taken from Star Street.

The speculation over Andrea Dawid only served to increase the aura surrounding Ammo Hanna. He was the only person in Bethlehem to have travelled to Amerka and make it back alive. When Jubrail’s father began to doze in the afternoon sun, Ammo Hanna would finally turn to Jubrail and mesmerize the young boy with tales of strange peoples, fantastical beasts, and enchanted cities. For 30 days and 30 nights he had journeyed across the great Atlasi Ocean on a ship powered by a combination of steam and sail, enduring the most squalid conditions. The idea of a vast ocean fascinated Jubrail who had never seen the sea, nor even a river. No running water passed through Bethlehem except the ancient aqueduct that carried water from the Pools of Suleiman to the south, but they were far away, and Jubrail was forbidden by his parents to stray that far. Instead he let his imagination run wild as Ammo Hanna described waves taller than mountains and terrifying creatures of the deep, bigger than the boat itself.

Somehow, Ammo Hanna had made it to Amerka in one piece. Immediately, he had set about investigating the place. What he found, he explained to Jubrail, was a new world in a frenzy of creation. A land of great cities in the making, inhabited by people from every part of the world, all arriving to make their fortune. Waiving his hands excitedly, he explained that economic opportunity there was limitless, especially for a merchant from Bethlehem selling Holy Land carvings. It was at this point that Jubrail’s father Yusef would stir from his sleep and begin to pay attention. The people there, Ammo Hanna explained, professed to be Christian, and they held a special reverence for anything connected to the Holy Land. They had flocked in droves to buy Ammo Hanna’s crosses and rosaries, leaving him wishing he had carried greater quantities with him from Bethlehem.

Ammo Hanna had begun his journey around Amerka in a teeming port city named Rio de Janeiro. Located in a huge bay ringed by densely forested mountains, Rio had been his home for several weeks. He had been surprised to discover people there speaking the same languages and worshipping the same saints as some of the Franciscan friars who lived in Bethlehem. But once he ventured into the jungle-clad interior, he could no longer understand the people, nor could he recognize their saints. The landscape there was unlike anything that existed in Palestine: a dense mass of greenery where plants and animals burst from every crevice. Everyone and everything permanently dripped with water, either from the torrential daily downpours or the constant sweating brought on by the unrelenting humidity. Lurking in the dense forests were all manner of strange beasts.

As he listened with eyes wide open, Jubrail could feel his own skin burning with the poison of a giant tarantula, hear the barking of howler monkeys in the valley, and see crocodiles slinking across the riwaq of Hosh Dabdoub. He memorized the names of the brightly colored birds and poisonous snakes, and he drew maps of the coastline of Amerka as he followed Ammo Hanna’s meandering monologue.

Many people in Bethlehem were not sure whether Ammo Hanna’s tales could be trusted. Some laughed and called him a khurafa who had never made it farther than the island of Cyprus. Others were more willing to believe that he had crossed the Atlasi Ocean but suspected his tales were full of fanciful exaggeration, especially those concerning the fantastical beasts of the jungle. But the young Jubrail hung on his every word, finding himself transported to another world as he listened to his tales of Amerka.

After Ammo Hanna left the house, Jubrail would walk down to the terraced slopes beneath Hosh Dabdoub to search for cicadas, lizards, and snails among the apricot and fig trees. He would imagine the lizards were the crocodiles that Ammo Hanna had spoken of, and that the olive orchard at the bottom of the valley was a dense rainforest, full of man-eating plants hanging precariously overhead.

Sometimes Jubrail would wander northwards, up the hill past the last buildings on Ras Ifteis. Following the road out of town, he would stop at the fork where it met with Hebron Road. Just past this junction in the direction of Jerusalem was Qubbet Rahil, the small domed structure that marked the boundary of the Bethlehem district and the outer edge of Jubrail’s known world. It was said that the dome contained the tomb of Rahil, the wife of Yaqub in the Holy Book who had died when travelling that road. Christian and Muslim women went there to ask for favors from Rahil, and occasionally Jubrail would see strange-looking men dressed in long black coats, rocking back and forth as they uttered prayers in an unintelligible language.*4 Peering in through one of the windows, he would observe with a mixture of fear and curiosity the surprisingly long ringlets of hair descending from their black fur caps. Was this how people in Amerka looked, he wondered? Returning home, he pulled out the maps he had drawn of Amerka, based on Ammo Hanna’s tales. As he studied those maps, he began to plan his own journeys. He told himself that one day he too would travel the dangerous road that stretched beyond Qubbet Rahil towards Jerusalem and the world beyond.

*1 The character of Ammo Hanna is based on a real person, Hanna Khalil Ibrahim Morcos, who was born in Bethlehem in 1824 and died there in 1900. The former Syrian consul in São Paulo, Majid Radawi, lists Hanna Khalil Morcos as the first migrant from Syria and Palestine to arrive in Brazil in 1851. See Majid Radawi, Al-Hijra al-Arabiyya ila al-Barazil 1870–1986 (Damascus: Dar Tlas, 1989), p. 48. The Bethlehem Latin Parish records show that his eldest son Khalil died in “America” (in the general sense) in 1883.

*2 The story of Abdullah Hazboun and his career with Napoleon’s “Mamelouks de la Garde” is recounted in Ian Coller, Arab France: Islam and the Making of Modern Europe, 1798–1831 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), pp.131–2 and 148–50.

*3 His death is recorded in the Bethlehem Latin Parish archives on September 7, 1796 with the sole note “morto in Latin America.”

*4 This description is inspired by Jabra Ibrahim Jabra’s account of his visits to Rachel’s Tomb when he lived in Hosh Dabdoub as a young boy in the 1920s. See Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, al-bi’r al-ula: fusul min sirah dhatiyah (Beirut: al-mu’assisah al-‘arabiyah lil-dirasat wa al-nashr, 2001), p.89.