The term “branding” is still contested when linked to nations; colleagues in Palestine would argue that the term “promotion” could have a more positive impact; in fact, this article will promote nation-branding in Palestinian cities. Scholars automatically link branding to products, business, and trade. It is not easy to imagine the nation as a brand. A nation cannot remake itself in the same way as a company that launches a new product.

Branding a nation is inspired by its national identity, which started to emerge with the evolution of the nation-states. It relies heavily on people’s attachment to shared land, shared history, shared language, shared culture, religion, clothing, behaviors, values, and attitudes or positions in dealing with internal and external variables. It is crucial to distinguish the identity of a nation, which is usually done through studying the elements on which a nation promotes itself using public diplomacy. Public diplomacy is a soft power’s key instrument which cannot be ignored. In soft power, the narrative and the reality have to reflect each other. A nation’s identity is partly inherited from history and partly a continuing construction. There are aspects of national reputation that can be altered. Even the inherited parts of national reputation are open to revision as time goes by.

States have come a long way in their nation-branding, and Palestine cannot remain indifferent. This piece aims to address the importance of Palestinian city branding and to further shed light on how this could be done. Based on case studies of other successful cities in introducing a number of elements that shape a national identity, this article aims also to inspire scholars, policy makers, ministers, governors, and mayors in determining what is worth promoting in Palestine that would lead to successful branding of Palestinian cities locally and internationally. Given that very little effort has gone into nation branding in Palestine, this article will highlight its importance in serving the national cause and the strategic national goals through responding to two questions: What is nation/city branding? What is the Palestine that we aspire to promote?

Nation/city branding

The concept consists of two words: nation – the people (citizens, outsiders, refugees, etc.) and branding – a purely business term that was later introduced into the area of politics and diplomacy and that attempts to answer two questions: What do we want to promote? and What do nations promote? The theoretical framework relies heavily on the work of the pioneers of nation branding*1: Simon Anholt, Wally Olins, Tom Fletcher, and Joseph Nye.

Branding a nation is inspired by its national identity which is largely a matter of stereotypes, familiar images, and associations. Most national identities are static. Simon Anholt, who is often referred to as the originator of nation branding, lists six channels of influence as the main elements of national identity, or as he calls it, competitive identity: people, culture, investments, policy, brands, and tourism. Anholt’s list leaves out at least one important element of national reputation – history, especially political history, the big things that the nation has done or failed to do, the things it has stood for or perhaps betrayed.*2

The above-mentioned list explains why Italian cities, for example, rank high in nation-branding surveys, given Italy’s strengths in culture, tourism, brands, and the bright image of its people. However, nation branding is controversial. British marketing guru Wally Olins was one of the first to use the term “branding” to promote a national identity and believed it wise to adapt business terms to politics and diplomacy. Nevertheless, there are those who prefer to refer to it as public diplomacy instead – the people who were offended by the term since it implied that the nation was a PRODUCT!

The above-mentioned list explains why Italian cities, for example, rank high in nation-branding surveys, given Italy’s strengths in culture, tourism, brands, and the bright image of its people. However, nation branding is controversial. British marketing guru Wally Olins was one of the first to use the term “branding” to promote a national identity and believed it wise to adapt business terms to politics and diplomacy. Nevertheless, there are those who prefer to refer to it as public diplomacy instead – the people who were offended by the term since it implied that the nation was a PRODUCT!

When I first talked about branding the Palestinian nation and the nation as a brand, a number of my colleagues suggested the use of other political terms. The term is still contested among scholars in Palestine, and resistance to the term is huge because of its business dimension. Despite the differences, we can’t deny that the term is catchy, attractive, and accommodates today’s needs and trends. Palestine cannot remain indifferent!

In a process of nation branding, it is wise to go back to the manageable elements on which we can rely and which are subject to change: leadership, culture, cuisine, individual accomplishments, fashion and design à embroidery, agriculture, and products.

Nations are already de facto brands, Olins argues, as they reflect their assets, attributes, and liabilities to a public at large, whether intentionally or not. Nation branding is largely perceived as a rhetorical equivalent to national identity, hence there is nothing particularly novel about the concept of branding the nation; only the word “brand” is new. National image, national identity, and national reputations are all terms traditionally used in this arena, and they don’t seem to provoke the same hostility as “brand.” Nye’s understanding of soft power is the general attitude, perception, or image that a country’s citizens have with regard to a foreign country, mainly favorable conceptions towards a foreign country.

To better understand branding, let us look at different examples. In branding for Lisbon/Portugal, the soccer player Cristiano Ronaldo was determined to be a national brand, and the Portuguese chose to brand themselves with his initials CR7. Today, if you read, hear about, or visit Lisbon, you will find a lot related to CR7: clothing, hotels, restaurants, cafés, toys, and games, all under his initials. Whether or not we like soccer, CR has become an attractive brand for his country. For Portuguese nation branding, the people chose tourism, cuisine, culture, and sports rather than their history of conquering the world.

To better understand branding, let us look at different examples. In branding for Lisbon/Portugal, the soccer player Cristiano Ronaldo was determined to be a national brand, and the Portuguese chose to brand themselves with his initials CR7. Today, if you read, hear about, or visit Lisbon, you will find a lot related to CR7: clothing, hotels, restaurants, cafés, toys, and games, all under his initials. Whether or not we like soccer, CR has become an attractive brand for his country. For Portuguese nation branding, the people chose tourism, cuisine, culture, and sports rather than their history of conquering the world.

Let’s take Italy as another example. What comes to mind at the mention of Italy? Well, most of us would think of certain cities, islands, and products, for example, pasta, Juventus and AC Milan, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, Venice, Vivaldi and Verdi, pizza and parmesan cheese, basil and tomatoes and mozzarella, Julius Caesar, the Coliseum, gelato, the Mafia, Rome, and Lamborghini. Some might think of Italian clothing brands, depending on personal interests, but it is not likely that any of us would think of Italian politics, for example! Italy has a wonderful national reputation for its culture – from Renaissance painting to modern cuisine – but a very poor political reputation.

Tom Fletcher puts the national story at the heart of what he describes as magnetic power, which is close in meaning to Joseph Nye’s attractive power. So how do nation-states use their magnetic power in the digital age? Three ideas should be considered here: having a strong national story; knowing how to tell it; and knowing how and when to mix the tools. To have soft power, a nation needs an attractive national story, a narrative that encourages others to support, or not to obstruct, its strategic objectives. There is a difference between, on one hand, national inventions that are used and admired, and which are elements of national reputation, and on the other, soft power, the ability of a nation to set the agenda and achieve its objectives without using force. The national reputation of the United States as the source of Apple, Facebook, Google, and other Silicon Valley-style modern miracles, and the slogan “I have a dream,” reflects America’s cultural influence, exercised through products that almost define modern living. This is what matters for a successful American nation branding, the cultural and commercial aspects of national reputation must be kept in perspective.

The astonishing success of Harry Potter, or the Royal Shakespeare Company, make Britain a soft power superpower. Like Italy, the United Kingdom has many national assets: the Premier League and the Monarchy, which are important elements in shaping the nation brand of Britain and how it is perceived by others.

The astonishing success of Harry Potter, or the Royal Shakespeare Company, make Britain a soft power superpower. Like Italy, the United Kingdom has many national assets: the Premier League and the Monarchy, which are important elements in shaping the nation brand of Britain and how it is perceived by others.

Germany’s national reputation may be static year by year, but the transformation of Germany over the decades has been heroic. This change has been founded on a self-aware national decision by millions of individuals acting to break with the past by accepting guilt, the “moral burden” of the barbarity of the Nazi era. It is remarkable that after WWII the guilt was internalized and became part of the German national identity. Germany is now the second-most admired country in the world after Canada, according to a BBC “country ratings” poll conducted by Globescan.*3 The elements in building that reputation include the success of Germany’s national brands, especially the cars that give Germany a strong association with positive qualities, such as engineering excellence, reliability, and style. There was a turning point in Germany’s reputation when Audi used a German language slogan that raises the “German-ness.” In other words, German-ness was negative, but they decided to put the German-ness back into the brand. It worked – the German-ness of Audi helped to sell the car. It can’t be contested nowadays that Audi as a German company is indeed the national identity of Germany, the whole idea and image of Germany became positive.

How Palestine is seen vs. how Palestinians want to be seen: victims vs. heroes

The role of Arab, regional, and international players in shaping Palestinian identity has led to introducing the Palestinians as refugees, victims, guerrilla fighters, stone throwers, poor people, and beggars to the international world. Whether we like it or not, the image of a Palestinian abroad is that of one who is stateless, ID-less, jobless.

If we look at Anholt’s six elements, we will easily discover that identity for Palestinians is not only about the nation’s image but about the political image of its leader and the human capital of its heroes. For Palestine, it is important to study the personality of Yasser Arafat as an icon and a symbol that presents a positive image of the Palestinian national narrative that symbolized resistance and perseverance. Arafat’s name became linked to the Palestinian struggle worldwide. Leaders or personalities are human capital for Palestine and include poets, artists, and the figures who managed to penetrate the international borders with their soft-skill gifts. In order to counter the image of a victim, why not introduce the heroes? Palestinians are perceived poorly and with sympathy. In Palestine’s nation branding, there exist a number of already-established brands, including the Trio Joubran, three musicians – brothers – who have taken the oud to world-class music; DAM, young Palestinian brothers who focus on conflict and poverty using Rap music; the late singer Reem Banna, another Palestinian music icon that went worldwide and managed to gather the love of millions around the globe; athletes such as The Speed Sisters, the first ladies-only speed-racing group not only in the Arab world but also in the entire Middle East. Poets such as Mahmoud Darwish, Ghassan Kanafani, and others had already brought Palestine to the world in various languages. And Palestine is rich in cartoon-art celebrities: Naji Ali, Mohamed Sabaaneh, and many others gained the attention and inspiration of the world through their cartoons and posters; artists such as Nabil Anani, Bashar Hroub, Tayseer Barakat, Laila Shawa, etc. who participate in famous world exhibits and galleries; journals and publications such as This Week in Palestine or Al-Quds newspaper, where identity is deeply engraved in their pages; scholars such as Edward Said; imprisoned child heroes such as Ahed Tamimi or Shadi Ahmad and the photographer Arine Rinawi, a young woman who managed to reshape the field of photography in Palestine and elsewhere; and many others. These are humble examples of personalities that make Palestine unique, and they are established brands that Palestine can utilize in its nation branding by introducing the talents and skills that Palestine can put on the international scene, things that other nations can’t duplicate. Palestinian human capital is a major investment in building a national brand for Palestine in every city.

Tourism is another aspect of national branding, especially if focus is put on the old Palestinian cities, those listed on the UNESCO world heritage list. Jerusalem, Hebron, Jericho, Nablus, Battir, and Bethlehem have great significance for tourism, culture, history, and religion, and highlighting what makes them unique can attract attention and show the Palestine that we wish to promote.

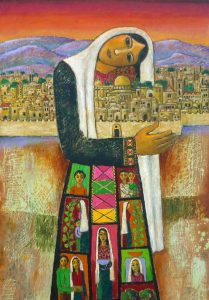

Photo from Palestine Image Bank.

Palestinian culture is a treasure – the traditional dress (thobe) that is hand embroidered, the dabka dance, the cuisine, and the amazing hospitality, among other things, make Palestinian culture very attractive. For a nation to change its image, it needs first to change its behavior. Then, equally important, it needs to tell others throughout the world about the changes. Images of a nation will not automatically change after the reality changes; thus the way for a nation to gain a better reputation is to communicate to the international audience how good it is. This practice is called nation branding.

The office of the prime minister should form a strategy group to envision what each city council could adopt and apply in the various cities to create monuments, museums, theaters, statues, and shops that carry various names or stories that make Palestine unique. The government needs to focus on the treasures of talented Palestinians and communicate their stories in order to have a positive impact on the image of Palestine. This form of nation branding is of crucial importance in identifying the uniqueness of Palestine – its people, culture, and landscape.

*1 Szondi, Gyorgy, Discussion Papers in Diplomacy, Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding: Conceptual Similarities and Difference, Clingendael: Netherlands Institute of International Relations, 2009.

*2 Anholt, S., Competitive Identity: The new brand management for nations, cities and regions, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2007.

*3 A total of 17,910 citizens across 19 countries were interviewed face-to-face or by telephone between December 26, 2016 and April 27, 2017. Polling was conducted for BBC World Service by the international polling firm GlobeScan and its research partners in each country, together with the Program for Public Consultation (PPC) at the University of Maryland www.globescan.com.