By Penny Johnson

Melville House Publishing, New York, 2019, 238 pages, $30

Reviewed by Mahmoud Muna – The bookseller of Jerusalem, The Educational Bookshop

The effect of the political conflict on the lives of Palestinians has been extensively studied and very well analyzed, but here, Penny Johnson looks at the “other” Palestinians, trying to see the extent to which the occupation has affected Palestinian wildlife and the natural environment. She shares openly about feeling “haunted by an innocent donkey bearing lethal explosives, but I am even more deeply troubled by the inattention to human life.”

The book is beautifully written, weaving together anecdotes from history and current political realities with zoological information about the animal habitat. The book is also rich with information about Palestinian traditions, norms, and cultural life in relation to animals, including perceptions, beliefs, myths, legends, and folktales.

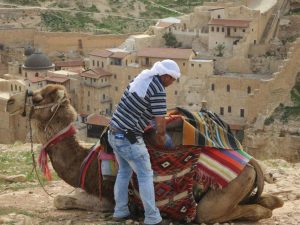

Each of the eight chapters focuses on particular creatures that are native to Palestine: camels, hyenas, goats, donkeys, cows, birds, boars, jackals, gazelles, ibexes, and wolves (sadly, no cats). By telling the story of these animals, Johnson narrates a beautiful tale of Palestine and its nature. Many of the stories have been researched using a wide range of sources, and many others are gleaned from her years of walking with her husband Raja in Palestine’s wilderness.

The book is a cheerful read, funny in parts but above all hard to put down. It is like taking a journey through a large garden, full of historical references and olden-day characters – an odyssey through Palestine’s hilltops and valleys, where actual historical events and political realities are blended to give voice to these seemingly mute mammals.

There is no doubt about the powerful environmental call presented in this book. Johnson argues for a “wider view of Palestine,” a way in which we can see and care for wildlife as an integral part of our human lives. She explores how unfortunate human intervention, in terms of urbanism (and, of course, the infamous wall), has had catastrophic consequences on animal life. Furthermore, the traditions of hunting and its promotion have caused a sharp decline in the number of many species, such as mountain gazelles, and the Arabian leopard remains critically endangered.

While she warns of confusing nature as pleasure with environment as a problem, Johnson concludes her book with a powerful examination of the excellent work that is being done by Palestine’s environmental, wildlife, and animal-welfare activists. She acknowledges the limitation of their work, noting that, fundamentally, with the human consequences of the escalating conflict so dire, “even the most dedicated animal-welfare activists have trouble seeing beyond the suffering of their human communities.”

This book is serious yet funny, well-researched yet easy to read. It is about animals as much as it is about humans; about Palestine as much as it is about the Levant. It is certainly a book that will cheer you up, even as it leaves a bag of salt in your stomach. If we don’t act soon, the land we love will be irreparably changed.

Read this book if you want to know why the British Mandate official in Palestine during the 1940s declared the goat to be Public Enemy Number One, and why the Israeli military governor determined “these cows are dangerous for the security of the state of Israel.” Read this book to learn why the Bassawi hunters expose their private parts when hunting hyenas, and what service the donkeys provided in wartime.